To my three readers–Hi, Anna!–I’ve been working on a play for a couple of years that I think would actually make a good TV series in these seriously troubled times. The title is up for grabs. Here’s part of Act 1.

Love, Lisa

WAVY DAVY’S PERPETUAL SOUP HOUSE KITCHEN

A PLAY by Lisa O’Hara

ACT I, SCENE 1

[AT RISE: Marv is typing at a laptop in a coffee shop. PHIL is sitting at the table sipping coffee and reading a book. They are in their 60s.]

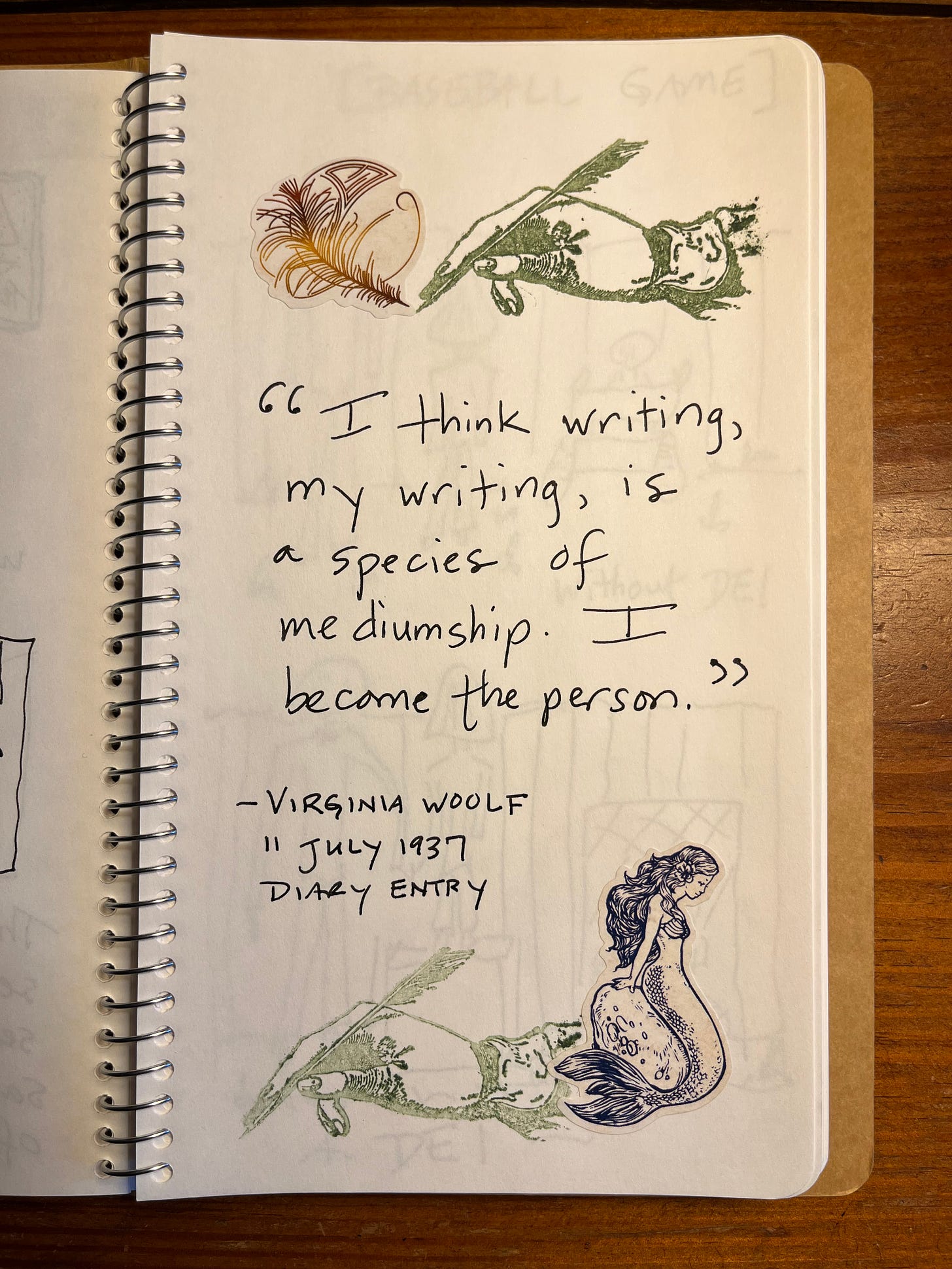

MARV: I want to tell this story with unflinching honesty.

PHIL: “Unflinching honesty.” So, what is “flinching honesty”?

MARV: [beat] Why do you do this, Phil?

PHIL: [beat] Because I care about meaning, Marv. What is “unflinching” honesty if there’s no opposite? If you are honest, you are honest. Why do you qualify it like a Book World critic? Are you worried what they will think? There’s no they, Marv. Only the truth.

MARV: There you go, Phil. [picking up an old argument, not necessarily his] We all know there’s a They and you know who they are, but you don’t really, do you, and that’s the maddening part. No, it’s not them [pointing] though that would be convenient for your politics, right? And how can They be playing you and playing them, those others on the opposite side as you…

PHIL: …the flinching ones…

MARV: …all the while taking all the fucking money? It’s like the aliens we all know exist, and so how is it no one has ever spilled that secret? So that’s how They operate, and it’s so fucking pissing fucked up. [MUSIC, good blues rock]

PHIL: Who are you right now? [MARV smiles. So does PHIL.]

SCENE 2

[Projected: 1988]

JUNIE: [outside the scene, stirring a big pot of soup, tasting, adding spices] Marv pulled up to the curb of the Leave It to Beaver street in Annandale, Virginia, in his used Ford Grenada, a color of brown no car should come in, and I remember he put it in park though he was always unsure about turning off the engine because of the other times it cut out, or just didn’t go, like when we were on Rt. 123 with our friends Gary and Phil, Marv flooring the gas for uphill acceleration and didn’t nothin’ happen, and he was screaming…

MARV: [looking up from laptop] Here’s some advice, kids. If you have to buy a car, don’t buy a used car, and if you have to buy a used car, don’t buy a Ford, and if you have to buy a Ford, don’t by a Grenada, and if you have to buy a Grenada, don’t buy a brown one!

JUNIE: But on this day, a humid but decent early summer day perfumed by freshly mown grass, Marv was not terrified we’d get rundown by a semi. He was beaming, glowing, about to show his bride, his love, me, their, our, new house. [MARV beams] Yes, on this July day in 1988, at the age of 38, he, Marvin Allen Frischberg, had done the thing he’d sworn on his bell-bottom jeans and tie-dye tee shirt at the 1968 Democratic National Convention he’d never do: use his earnings from a steady job in American government…

MARV: …all this, thanks to the fuckin’ man, of all things…

JUNIE: … to further suckle on the teat of American corporate capitalism by entering into a life phase of home ownership with a woman to whom he was wed. But there we were. And Marv was exhilarated.

[In shadow, a jubilant MAN gets out of a car; a WOMAN next to him stares out.]

JUNIE: Next to Marv in the used brown Ford Grenada was that very bride, aptly named June, Junie to everyone; together, what thirteen, fourteen years, married by our friend Kenny, dead of AIDS four years that August, who’d gotten a Universal Life certification out of the back of Rolling Stone to perform the ceremony, was it really nine years before, in the backyard of Gary’s “communal” house on Glebe Road…

MARV: [typing in cafe] …just a few miles outside the District. When Junie said, “Where are we?” I said, “Our house,” thinking total Graham Nash, and my Joni, my Junie, unclicked the barely operational seat belt, opened the passenger door, and…I shit you not, she began vomiting to the point of dry heaves…

JUNIE: And I was thinking, The Dry Heaves would be a great name for a band.

MARV: I was sure that Junie was really pregnant this time, and I was overcome with joy.

JUNIE: [lifting a ladle] Who wants soup?

SCENE 3

[Music. Projected:] 1973

[PHIL and MARV, aged 23 or so, are playing chess at the kitchen table in the Arlington, Virginia, kitchen on Glebe Road. It’s the first Watergate Summer. PHIL has just check-mated MARV again. GARY, also 23, who owns the house with his mother, enters from the kitchen with a bowl of soup and a stack of saltines.]

GARY: [setting down his bowl and crackers on a TV tray] You know who they are? I am they. I run the fucking world. I’ll prove it. [GARY uses the remote to turn off the Watergate hearings on television; he turns to flip on PHIL’s remote control stereo invention to turn on the radio, then flips it off. He then flips on another remote control to pull down the shade on the west-setting sun.]

PHIL: My inventions are useful.

GARY: I read all about this stuff! [GARY points to his stacks of Popular Mechanics magazines, his copies of National Review, his stack of articles from the Washington Star; possibly these are projected.] You think none of this matters, and that these bogus Senate hearings matter, okay, you’re wrong, but okay. You know what really runs all this? [gestures to room, to the world] Computers! Have you seen Phil’s computer room? Everything in the world will be run from those computers if we aren’t careful.

MARV: [lifting a pawn to move into position, first using it as a microphone] But who’s the man behind the computer? Who are you, Phil? What is your agenda?

PHIL: [into the “microphone” before Marv places it in position on the board; speaking now into his knight before positioning it] I’m nobody, frankly. I have no agenda. Just chaos for its own sake. That’s your they, Gary. And you can’t stop me, I mean them, I mean us. I’m two moves away from “check” for those playing at home. And so are the Watergate prosecutors. [Slams the knight onto the board. Marv quickly moves to capture the knight.]

GARY: Fuck you. [He turns on a tall, loud metal standing fan, directs it toward his chair, sits and eats.]

PHIL: [moving his queen] Language. Check.

[The phone rings, a ring in the living room and another ring from the kitchen, behind them. Note: All telephones of this period are black, heavy, rotary, and land lines. The kitchen phone is a wall unit.]

JUNIE: [from the kitchen; remains offstage until entrance] Hello?

[Beat, as Phil, listening, turns off the loud fan with another remote, Marv studies the board, and Gary stuffs crackers and soup.]

JUNIE: [gently, really asking] Davy, sweetie, are you high?

[PHIL laughs so hard he tips the whole board over. Marv moves to clean it up.]

CAROL ONE: [entering from hall wearing a mini dress and block heels and carrying a pocketbook, calls] Gary! Gary, I had to walk from the bus stop. Walk, Gary, again. God it’s hot. [Kicks off her shoes, throwing one at Gary; sees game.] Gee, I wonder who’s winning, Phil? Marv, why do you even try? Seriously, Gary, this is bullshit. Are you enjoying your late lunch?

GARY: [eats, hasn’t looked up] You. Said. Five. It’s three.

CAROL ONE: The firm closed early today, the bosses are taking a long weekend on the Eastern Shore.

GARY: And I would divine this how exactly? Why didn’t you call?

CAROL ONE: The line was busy all day. And I told you yesterday. Twice.

GARY: That motherfucking party line. I’m so sick of it.

JUNIE: Okay. Just a second. [calling out from kitchen] Can anyone drive me to the restaurant?

PHIL: I would but I won’t have time, sorry.

MARV: I would but no car. [ALL look at GARY, who doesn’t look up.]

JUNIE: Davy, no one is going to drive into the District now. I can try a bus. [beat] Okay, I’ll be ready.

[JUNIE enters. She is a Breck girl, an earth mother, Joni, and Janis, and Georgia O’Keeffe, depending on the lighting of the moment and who is looking.]

JUNIE: [going to the basement door] Darnell’s coming to get me in Davy’s car. Can someone get me later?

MARV: [gets up after placing chess pieces in a box, goes to Junie, presses into her and kisses her neck; she yields instantly] Come here for a minute. [They disappear into the basement, shutting the door.]

CAROL ONE: Give you any ideas, lover? [CAROL unbuttons her dress, straddles Gary in his chair. PHIL takes no notice as he checks his watch, finds his keys.]

GARY: Come off it, Carol! My mother will be home any minute.

PHIL: Okay, kids, time for my shift. Enjoy your Friday evening not having to write tomorrow’s top headlines.

GARY: For that rag that has it out for Nixon. What other lies are you going to print about him tonight?

PHIL: Gary, until you can admit you are bent, you will always be an angry little fascist.

GARY: Take it back.

PHIL: Which part?

GARY: Fuck you. Carol, let’s go. [Grabs her hand, heads upstairs. Carol squeals.]

[Screen door slamming is heard. GLADYS, a woman in her 50s, but with a full embrace of polyester, enters, carrying groceries, goes into the kitchen.]

GLADYS: Hi, Phil. Heading off? [PHIL kisses her cheek, jangles keys, and exits; GLADYS from kitchen.] What’s all this soup? It’s maybe a hundred degrees out there. Who’s watching the stove? Where is everyone? [Vague sounds of pounding, mattress springs, faint moans emerge from upstairs and basement; GLADYS, appearing oblivious, goes to living room and uses the remote to turn on radio full blast, and scene. The song is, perhaps, Charlie Rich “Behind Closed Doors” or Marvin Gaye “Let’s Get It On” or David Bowie “Space Oddity” or Barry White “I’m Gonna Love You Just a Little More, Baby” or another hit of the summer that you think fits the mood.]

SCENE 4

[The bustling kitchen of a restaurant, same late afternoon of 1973, a small black and white TV set with antennae shows Watergate hearings, end of day reportage, muffled sound. Two assistants, MARTIN and FRANKIE, watch as they chop vegetables, etc., and DAVY prepares to show JUNIE how to pull pin bones from fish. DAVY is a white man of 24 or so, in chef attire, a shorter Rock Hudson-meets-rock star whom his friends call “artistic.” DARNELL, a sweet, observant Black man, about 19, comes from the back carrying a white coat or apron, which he puts on.]

JUNIE: [standing amidst the chaos] Why am I here, sweetie? I don’t understand fine dining.

DAVY: [handing Junie an apron and guiding her to the sink] You are tonight’s pin bone wizard. Wash your hands. Mike’s out sick, and of all nights it’s a fish Friday, but here we are, and you are an artist, an angel with a needle, I need an artist. There are your tweezers, down there is the prepared fish—all you do is pull out the bones.

JUNIE: [putting on apron, walking over from the sink with dish cloth] Davy, sweetie, you do know that I push a needle in…

DAVY: [takes dish cloth from her] But you also take the pins out, and hurry, dear one, hurry, dinner starts at 6 PM. Chop, chop. [Turns off television set, demands] Martin! Frankie! Those Jell-O salads won’t unmold themselves! [They follow Davy into the next room.]

JUNIE: [opens the cooler and screams] Holy mother of pearl, my poor fingers…

DARNELL: I can help you. [They begin removing bones.] Each filet has about ten. Or twenty. [DARNELL smiles. JUNIE is meticulous, like an artist, as DARNELL points, supervises. Beat. Beat.]

DAVY: [offstage] Faster, faster, faster!

[JUNIE pulls a final bone as DARNELL transfers that fish to a waiting cooler and then lifts a new fish onto the board for JUNIE to attack. DAVY enters. He looks around, and plants a kiss on DARNELL’s neck as DARNELL turns and gives DAVY his lips. JUNIE, laser focused and very quick now, doesn’t notice. They separate as MARTIN and FRANKIE push backwards through the swinging doors bearing trays of perfectly molded green Jell-O with cabbage and carrots. Scene.]

SCENE 5

Davy’s Soup Rules [Projected, with music, and VO possibly.]

- READ THE RULES BEFORE YOU FUCKING TOUCH THIS POT.

- I AM NOT FUCKING KIDDING.

- Keep stove burner on LOW!

- Use the stainless steel pot only!

- Water only!

- Fresh vegetables only!

- NO MEAT! NO FISH! NO POULTRY! NO!

- NO STARCH! That includes NO POTATOES, NO PEAS, NO BEANS. NO!

- Herbs and salt OK.

- Stir occasionally.

- Keep lid on when not stirring or serving.

- Serve soup atop whatever starch or fish or meat makes you horny for life.

Act I, Scene 6

[SCENE: Kitchen table on Glebe, 1974; linoleum and chrome and four matching chairs and three mismated ones. MARV, PHIL, GARY, and DAVY sit with various mugs and Tupperware glasses. PHIL with a national paper, reading, begins to snort out a chuckle.]

PHIL: [reading] “Spiro Agnew disbarred.”

DAVY: Was he now.

GARY: I think Agnew got a rotten deal.

PHIL: The Maryland appeals court called him, “morally obtuse.”

MARV: [a mock scolding] Language, Phil!

DAVY: But can a sitting elected official really be the subject of an indictment? Isn’t a president, or a vice president, the moral equivalent of a king?

MARV: The morally obtuse equivalent. Yes. [DAVY and PHIL chuckle.]

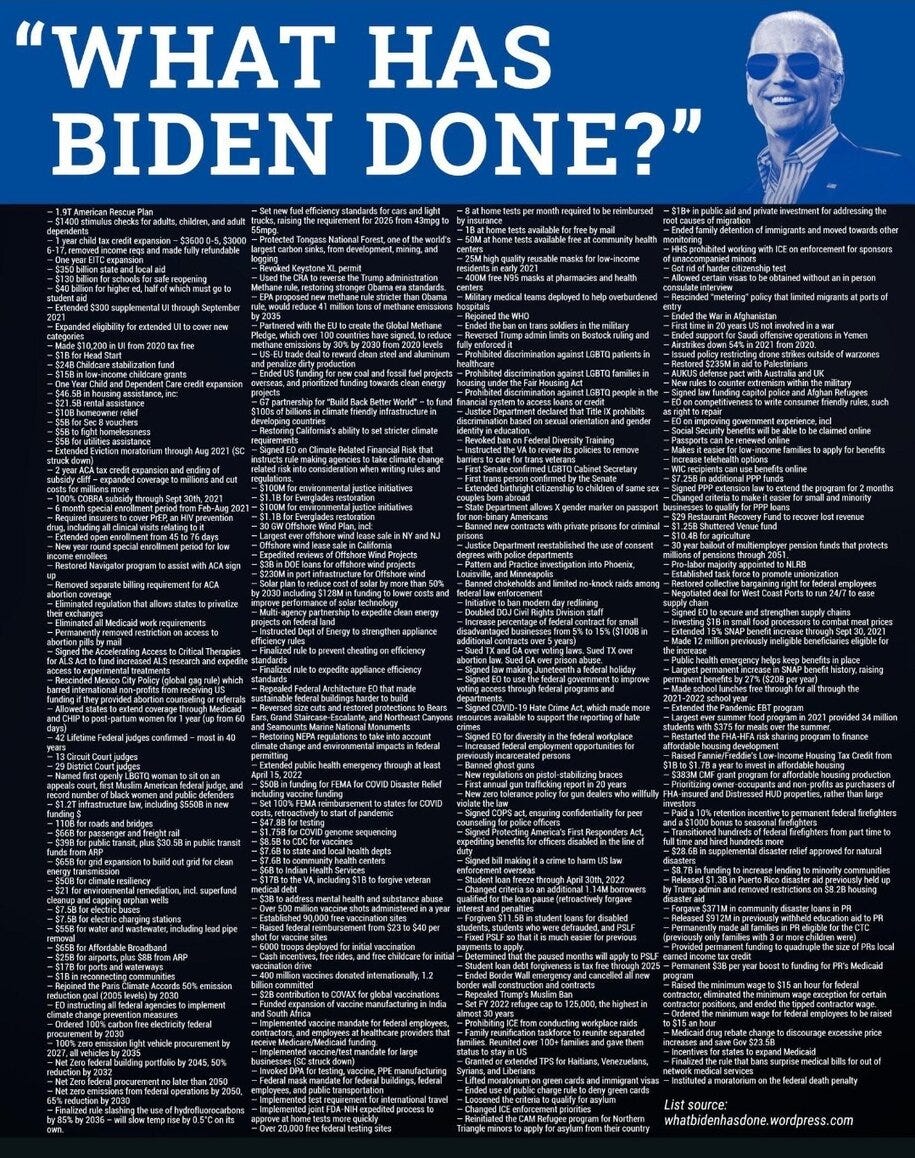

GARY: This nonsense is spiraling out of control. If they can come after Nixon, and Agnew, they can come after anyone…

PHIL: Maybe. If I made enough money to pay taxes, I’d pay them.

MARV: Except for the war taxes.

DAVY: Fuck the war taxes.

PHIL: Do you, Gary?

GARY: Do I what? [beat as others look at him] Any money I make is money I earn.

MARV: In cash, who’s to know?

[Junie interrupts waving an envelope.]

JUNIE: Hey, Gary.

GARY: Is that the rent?

PHIL: Your tax-free rent, oh Landlord.

DAVY: Do we Deep Throat him?

GARY: That’s your department.

DAVY: I’m here, I’m queer, but at least I pay my taxes. Mostly.

JUNIE: [observing; giggles] I… [stops her thought] … who wants soup?

DAVY: You what? You what? I saw that giggly gleam in your eye. You have the best face when you get an idea.

MARV: I feel art coming.

PHIL: [reaches to press MARV toward table, looks behind him] Art? Art who?

[Lights change, special light on JUNIE. VOICES fade out as music rises, e.g., “Eve of Destruction.” Collage art with painted photo or painting of the four friends around the kitchen table; gradually superimposed on each face are high school photos, ca. 1965. MARV, PHIL, GARY, and DAVY are fifteen years old.]

PHIL: [reading] The British Invasion is upon us.

DAVY: To say nothing of the Russians and the North Vietnamese.

GARY: You’re saying we shouldn’t fight the commies? The commies can go to hell.

MARV: [imitating GLADYS] Language!

PHIL: Now, boys, no politics at the table. [He gives a sieg heil, glances toward GARY while looking at MARV; locates a deck of cards.]

GARY: [looks under table] Mom?

DAVY: Beatles or Stones?

ALL: Beatles.

MARV: Acoustic Dylan or electric Dylan?

ALL: All the Dylans!

[PHIL deals cards; Davy takes out a baggy of weed as Gary finds rolling papers, if possible, Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” comes up, possibly a record put on by one of them.]

ALL: [singing as they pass a joint, play poker] “Look out kid

It’s somethin’ you did

God knows when

But you’re doin’ it again

You better duck down the alley way

Lookin’ for a new friend

The man in the coon-skin cap

By the big pen

Wants eleven dollar bills

You only got ten”

[Light shifts to JUNIE. VOICES fade out as music rises, Chubby Checker “The Twist,” lights change. Art montage superimposes school photos, ca. 1960. MARV, PHIL, GARY, and DAVY are ten years old.]

PHIL: [reading, carefully] “Richard Leaky…”

MARV: “Leaking?”

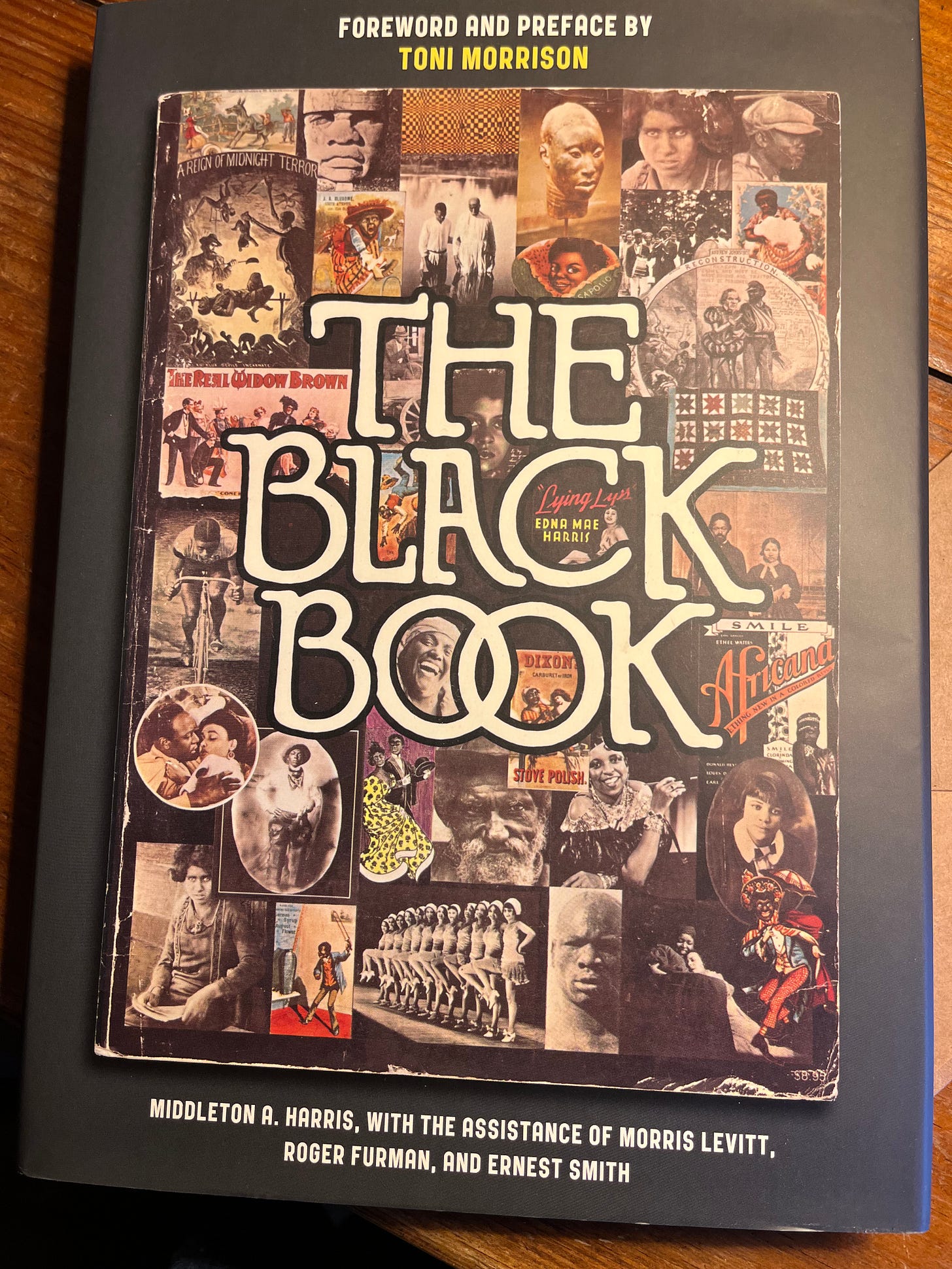

PHIL: [giggles, repeats] “Leaky… discovers our human ancestors in Africa.”

DAVY: [drawing his idea of one] And they are really, really old. [Shows picture to PHIL]

MARV: Not as old as dinosaurs. [Looks at Davy’s drawing.]

GARY: My dad says I am not a Negro.

MARV: What does that mean?

GARY: [shrugs] Dad says we are Americans and not Negroes from Africa.

PHIL: They don’t want you anyway, Gary. You can’t even twist. [twists]

MARV: [imitating his mother] Now, boys! That dance is immoral!

DAVY: How can anyone know where humans came from?

GARY: My dad says it’s aliens.

PHIL: So are we Americans or aliens?

DAVY: I think it could be aliens. I must be an alien. I just know it.

MARV: Where did the aliens come from?

[Light on JUNIE. Music changes. Tennessee Ernie Ford, “Ballad of Davy Crockett.” Montage: Collage art with photo or painting of the four friends around the kitchen table; gradually superimposed on each face is a first grade black and white photo ca. 1955. Lights change. MARV, PHIL, GARY, and DAVY are now six years old.]

PHIL: [looking at a comic book] My dad says they are cancelling Red Ryder.

DAVY: They are? How come?

GARY: My dad says Red Ryder got a rotten deal.

PHIL: My dad said Red got “damn boring.”

MARV: [imitating his mother] Language! [The boys giggle.]

GARY: This comic cancelling stuff is crazy! It’s not fair. It’s all gonna be like Batman, and I can’t stand Batman. Stupid capes!

DAVY: I only like comics where the men wear capes.

PHIL: You like the capes!

MARV: I think a man in a mask and a cape fighting crime is neato.

GARY: Matt Dillon wears a mask, but he doesn’t wear a cape, and Gunsmoke is still neat.

DAVY: You mean the Long [sic] Ranger wears a mask.

[Lights out on BOYS and up on table in 1974, the MEN playing cards, smoking, changing the lyrics to songs, perhaps. Lights separately on JUNIE gazing on finished work of a large, full collage of the eras of friendship. Song collage, closing perhaps with Joni Mitchell’s “The Circle Game”: “And the seasons they go round and round/ And the painted ponies go up and down/ We’re captive on a carousel of time…”]

DAVY: [entering with a bowl of munchies; to “My Boyfriend’s Back”] “My boyfriend’s black and there’s gonna be trouble, hey ma, hey ma, my boyfriend’s black…”

[CAROL ONE, enters with Lysol.]

CAROL ONE: You are terrible.

PHIL: [entering with a bong; to “Hey, Jude”] “Hey, doob, I want you bad,/ take my dad’s bong, and make it better…”

CAROL ONE: You think you are so cute.

GARY: [sees clock; grabbing bong and waving away smoke, takes Lysol from CAROL ONE.] My mom’s gonna be home soon, you guys.

MARV: [Three Dog Night’s “Mama Told Me Not to Come,” to GARY] “Mama told me not to come…” [MARV, PHIL, and DAVY join in, dancing, as music gains in volume.]

[JUNIE, smiling, holds her gaze on this scene as BLACKOUT.]

Act I, Scene 7

[Kitchen at Glebe Road, 1977. At table are two Vietnam vets, ROGER and MARK, both white men around age 30, in motorcycle gear. JUNIE ladles out soup into mismated mugs and brings them to the table where spoons and napkins are placed. GLADYS enters, smoking a cigarette, coughing, greeting the men.]

GLADYS: So how does Junie know you?

ROGER: Well, she was at one of our gatherings, to help veterans. Junie offered to do a poster for our meetings. And then we saw her at Safeway that time. Started talking.

GLADYS: You both live in Arlington?

MARK: Yes, ma’am. Appreciate the soup.

ROGER: Well, Mark’s closer to D.C. than I am. You know, a lot of people spit on the veterans.

GLADYS: Well, not Junie, she lost a brother, you know.

MARK: That’s what we hear.

GLADYS: That was 1966, ’67, wasn’t it? I mean, no sooner shipped over, wasn’t it?

[Lights up on area, living room, somewhere in Arlington, Virginia, ca. 1965, TIM MACNEIL in uniform, his father COL. DONALD MACNEIL in khakis, and his mother VIVIAN MACNEIL pose for a photograph. His sister JUNE, aged 17, takes the photo. After the flash goes off, VIVIAN begins weeping; TIM comforts her. COL. MACNEIL pats his son’s shoulder, picks up his kit; TIM hugs JUNE, goes with his father. VIVIAN pours a drink.]

MARK: So during Rolling Thunder, huh.

JUNIE: 1967. Yeah. [She pauses, only continues as others look to her for more information.] Tim enlisted as soon as war was declared. [Adding, unusually] Our dad was career Army.

ROGER: How old?

JUNIE: Eighteen, almost nineteen.

MARK: How old were you?

JUNIE: Seventeen.

GLADYS: Irish twins.

JUNIE: [picking up a loaf] Bread?

[MARV enters with satchel.]

MARV: Hello.

GLADYS: We have company. Marvin, meet Roger and Mark.

JUNIE: Soup?

MARV: Oh, right, the guys from the meeting. How ya doin’?

GLADYS: [to MARV] You know, it’s odd, isn’t it, that none of you boys served. [To MARK and ROGER, who pause in their eating.]

MARV: We didn’t. [Taking soup from JUNIE, to MARK and ROGER] I know I said this the other week, but I protested against the war. Our friend Phil was 4F for his flat feet. Davy was queer, but they wouldn’t believe him, so he went to school and was an art teacher for a while. I went to college and taught math—my parents came over during the Holocaust, and my mom would’ve gone nuts if I’d gone off to fight, but even still….

ROGER: What’s the Holocaust?

MARV: [patiently, instructively] Hitler’s genocide of Jews. Mostly Jews, but also homosexuals, resistance fighters…obviously not as known as it should be. Something like six million Jews were killed.

MARK: So you’re a Jew? [MARV looks up.] It’s cool. I don’t think I’ve, you know, ever talked to one before. That I knew of.

[PHIL enters, followed by GARY, in mid-discussion.]

GARY: So you’re saying that you actually think Carter has any fucking shot at all of getting peace in the…

PHIL: Oh, hello.

GLADYS: Gary, language, not in front of company. [PHIL and MARV grin without looking at each other.]

Copyright Lisa L. O’Hara 2023-2025. All rights reserved.