Playing for Time

Covering a Change

Back when I was a drama director, my school’s orchestra teacher, Mr. T, had to fill in as the conductor of the orchestra for The Music Man when not one band director but two had to bow out (one for a family tragedy, the other because he’d been asked to be an interim principal at another high school). Mr. T, who had strenuously avoided conducting kids in a pit, was a terrific conductor and teacher, but knew nothing about musical theater. One day in the library, where he’d tracked me down, he asked me about a bunch of music on the sheet. Those marks (Greek to me) turned out to be the opening of “Wells Fargo Wagon,” and just as Mr. T knew nothing about putting on a show, I knew nothing about reading music.

He asked, “You don’t need all this music, do you?”

Oh, yes, we do.

“Why? It’s a lot of music.”

Because all this intro music is covering a set change.

“Covering?”

Right—the orchestra plays while we do all this work behind the curtain, or on a darkened stage, and when the lights come up, the music stops. In fact (I explained to the perplexed Mr. T) we will probably need more than that, so you will need to pick a spot you can back up to and play it again. It’s called, Vamp until ready. (And here I sang a little, “Bum, bum, bum, bum” [key change] “bum bum bum bum…” and then, “Now the lights come up and Marion enters…and music fades….”)

To his credit, Mr. T listened, learned, and got it. I was really happy to work with him, and he was in turn grateful to conduct the pit, though once was enough (it’s a 10-week after school time commitment for no pay), because he’d had no idea what went into it or how interesting it was to watch a show evolve in rehearsals to performance. And since pit orchestras are among the biggest employers of musicians, even a high school production of The Music Man is real world work experience for the kids.

I was thinking one morning this week about that expression, “vamp until ready,” which I learned in college as a theatre major under the direction of the late, great Maureen Shea. I used to watch her direct even on shows I had nothing to do with, only one of which was a musical during my four years. (Sometimes, you only need one strong experience to bank away knowledge for a lifetime.) I’ve noticed that “vamp until ready” applies to my corporate work life, and by extension to my life in general right now, but oddly enough, also to world leaders; the question is, How long can we keep this up?

“Figure It Out”

Among the looniest takeaways from all the years of public or private education for Americans in general over the past many decades is the notion that teachers had nothing to do with our learning. Instead, too many who go on to adulthood, especially those who become “leaders,” are under the delusion that they themselves figured out how to read, write, calculate, observe, and think irrespective of the educators they had over the years; indeed, some believe they learned in spite of them (and however much we may not like a teacher, we learn that, don’t we?). Ergo, when these former students go on to lead projects for, say, the government or a corporation, they begin by telling you, the workers, about a vision, the market, and the research, and to explain your titles and roles in the creation of this new initiative or project.

And when you ask, “What do you want me to do, or how can I best be of service?” their standard answer is, all too frequently, “Figure it out.”

Or, worse, “I’ll know it when I see it.”

I believe this is because they, the leaders, know we have to create something, but beyond a pillowy, sparkly dream, they more or less have no idea how to execute it. Or, by contrast, they know exactly what they want to do and give innumerable lectures in meetings trying to get your buy in. Talk, talk, talk, talk, talk until blue in the face. And after two decades in corporate life, where I moved from worker bee to senior whatever, the same thing holds true, whatever the leadership style: No one in leadership gives a tinker’s damn what anyone on my level “thinks.” Nothing we “do” or “make” will ever be what they want because they have zero curiosity about what we on the ground are going through. Life as Monty Python sketch. So, in order not to go mad and to keep your salary and benefits, you learn that the best thing to do is “look busy,” or as we say in show biz, vamp until ready.

And one day, suddenly, the curtain will open, the lights will come up, and the leader will shout, “I need everyone on stage NOW.” And with the wave of a wand, the leader will tell you what they want you to do. Only now, instead of 12 months to make the product, you have one. And you’d better not fuck it up.

Work Until Living

Everything on earth is in crisis—the climate, the untold effects of war and natural disaster, governments taken over by the right-wing march to fascism—and where once we had (we thought) plenty of lead time to solve everything, the time has been lost primarily due to lack of capable leadership, or because good leaders have been thwarted by others devoid of curiosity and compassion and belief in something true. I’m looking at free-press publishers as well as mayors and governors and representatives and presidents. Even good leaders can’t move forward when no one else is cooperating. How many times must we quote “The Second Coming”? The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are filled with passionate intensity.

But being a lowly worker bee, I can’t lead the world to victory over the latest crises. As a result, I find myself stuck with my own life to figure out. That’s where most of us are.

Where is my leader, I wonder, the one who will announce to me what I’m supposed to do and how I’m supposed to do it and what the deadline is? A lot of us could use a purpose, not life and death, maybe, not with stakes beyond what we can handle and live in joy at the same time, but I mean some kind of purpose that makes the work of living each day something beyond mere survival. Many people have love in their lives, a mate or children, to give them that level of desire for living. Most of us, however, do not. And that’s when we look to art, I guess, whether or not we have talent or direction.

I think, in fact, the worlds of business and government (and even puny human life) would do well to take a cue from the world of musical theater.

At the first production meeting for an upcoming show, the director (in charge of the whole shebang) sits with the musical director, set designer, lighting designer, costume designer, choreographer, and stage manager (and if at all possible the original authors, but I was never that lucky director) around a big table, scripts in hand. First, a good director will share the vision she has for the production. A really good director will move forward by genuinely asking each of the players assembled what they think about the script and score, looking at their preliminary sketches and notes. Next, an even better director listens to each person in turn, not as a courtesy but because she really wants to know what they think. The stage manager takes notes. Perhaps they break for tea and donuts. And if a director is excellent, she will tell back to each of the players all the ideas they shared that she would really like to incorporate. Then she will give them an assignment, which is to take everything they’ve talked about today and make adjustments to their previous ideas; this includes the director. And so the work goes. Ultimately, the director decides on the production concept and must make sure that all the pieces of the production, including performances, are working in concert (the setting not modern when the costumes are 19th century, say). All this work evolves over the course of, say, ten weeks, leading to the technical rehearsal with the performers. The tickets are sold, the show must go on.

Unlike world leaders faced with the problem of war or global warming, or a CEO launching a new, useful product in corporate America, in theater a leader is not allowed to go into denial, sit around making speeches or ringing hands or having drinks with other theater folks before deciding to finally start rehearsals a week before opening night.

There is in the theater what Dr. King called “the fierce urgency of now.” (How is this not true for too many when it comes to war and the planet, when the stakes couldn’t be higher?)

In the months or weeks leading up to an opening night of a show, the work has to be ongoing and purposeful (the theater is booked), the collaborations real (the tickets are sold), the director clearly in charge of pulling it all together. That’s the deal. A show might succeed or flop, but no one is setting out to fail. And the work in any case will help everyone involved be better trained for the next one. And there will always be a next one.

The theater process is worth studying, I think, because while the stakes often feel like life and death, because artists care so deeply about success, the truth is no one dies. All we ever have against us, whatever our job, is time. In the theater, every show needs two more weeks. Because we don’t have it, we go on, we work, we do our best. We don’t give up.

Shouldn’t that be everywhere? With everyone?

More and more, I’m wondering if I’m feeling a crushing sense of my own life off the rails because all around me I sense the director left the building; I feel this enormous lack of sentience, wisdom, and leadership in the larger world. It’s hard to think of my little life having value or meaning when the highest of stakes, life and death issues, are being played for farce among, say, elected Republicans in our House of Representatives, where the instigators receive no rebuke in the headlines (while “the slap” gets unending coverage). How long can we keep up this vamp before the audience in fact dies?

Troubling Deaf Heaven

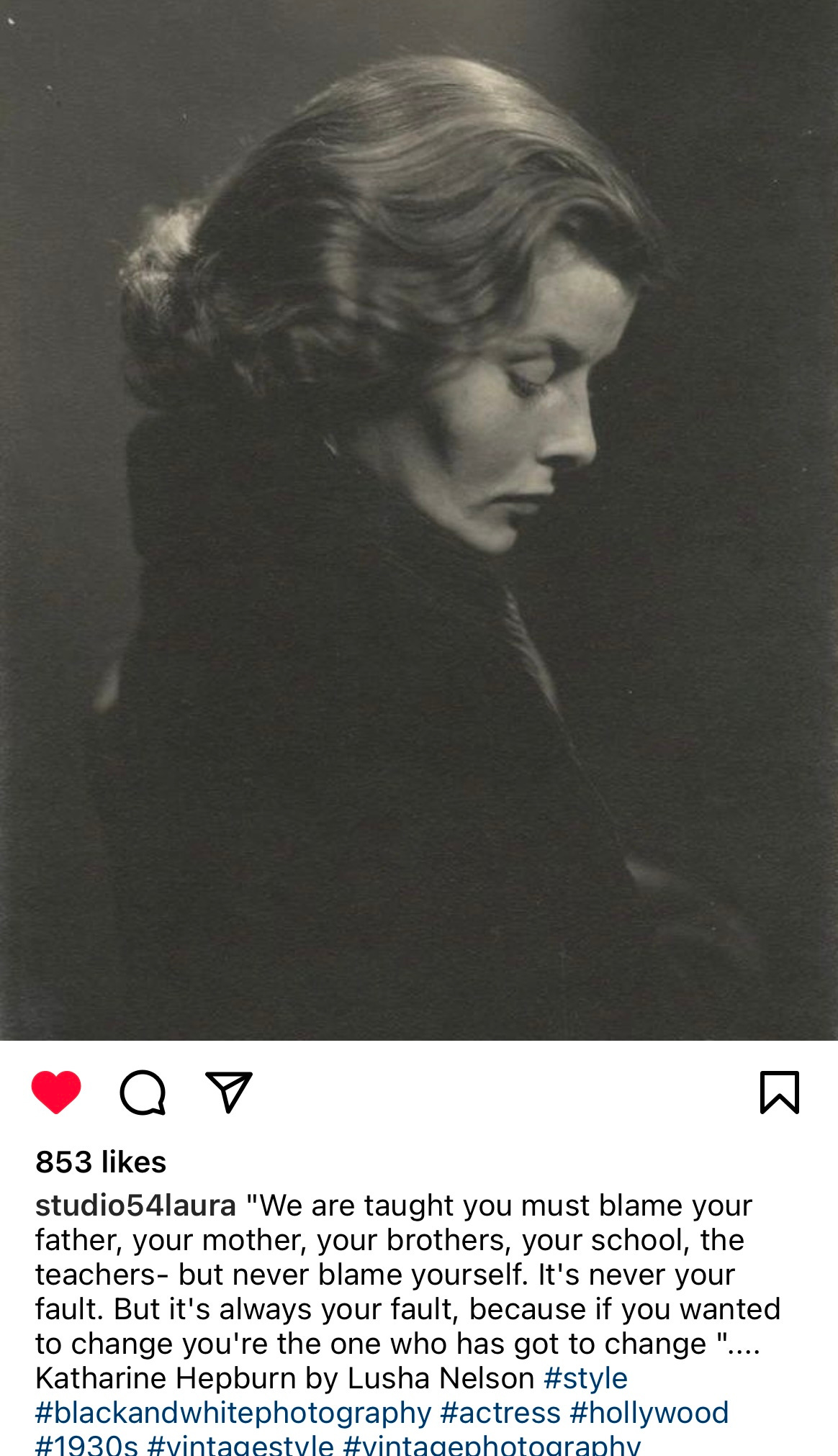

“Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,” haply I ran across this quote from my idol Katharine Hepburn via Instagram. She’s absolutely right—the only one who has to change in the above scenarios is I. Yet how, I wonder. And to what end?

Love or something like it, vamp 2-3-4,

Miss O’