The Body in Transition

A friend texted me Saturday afternoon to ask when I will be writing another blog installment, after the previous post about caring for my folks, and I texted back, “Lather. Rinse. Repeat. There’s your blog.” What else is there to say? Day melts into day into day into day, as the days go by, every problem you thought you’d resolved (meds, meals, moving through exercise) back to square one, recalcitrance.

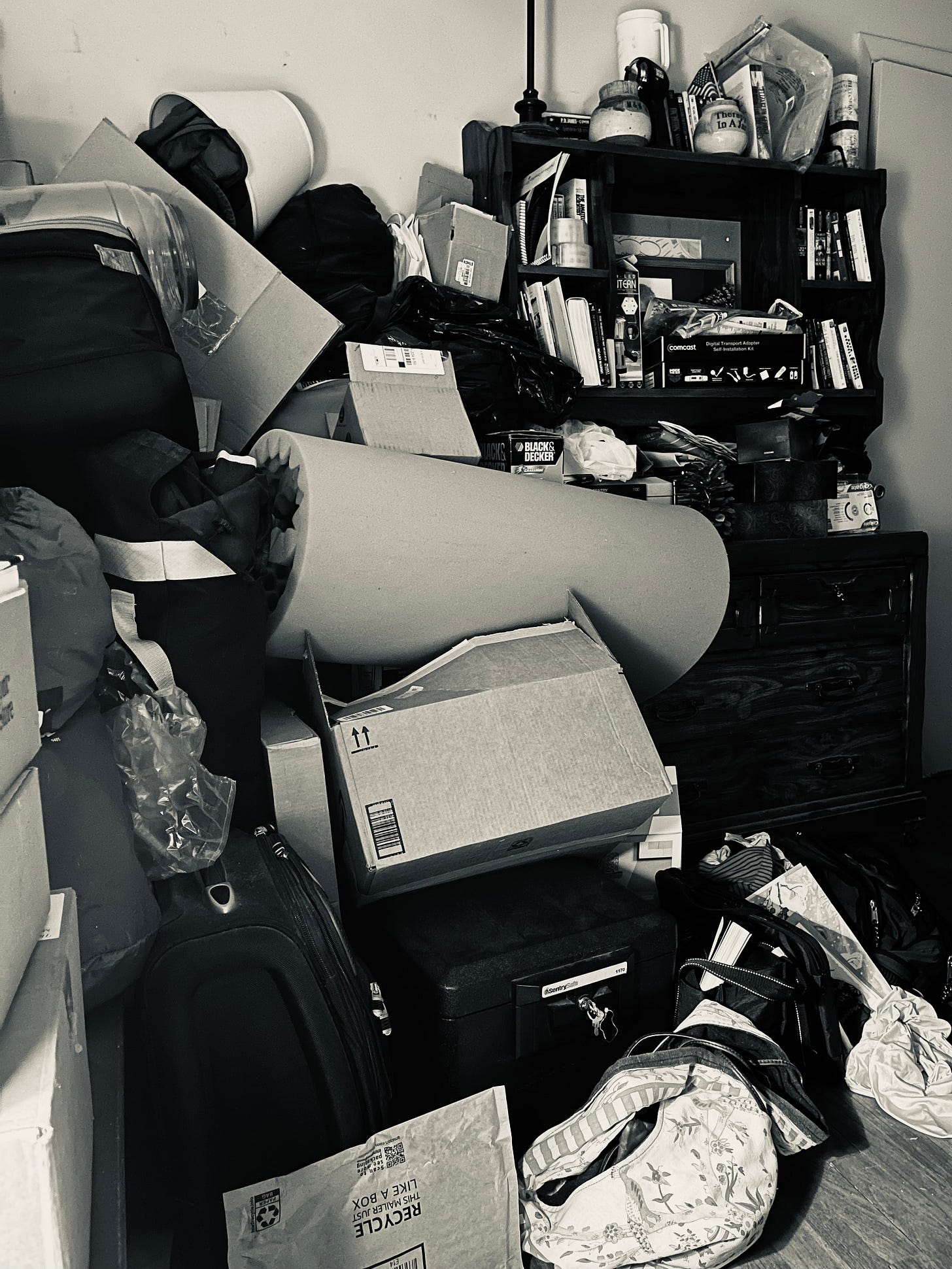

Sunday was a fragile day. I’d awakened about 1 AM, weeping, realizing how impossible it is for me to leave, trying to figure out if I should just sell my New York apartment and the bulk of my possessions and just move here, or try to wait it out. I don’t want to move back here. But I’m not sure what choice I have. I somehow got back to sleep for a few hours. Later, taking my dinner plate out into the playroom (where my parents live now), I startled my dad, whose Coke flew into the air. I set down my plate, went into the kitchen, got a went rag, wiped down the rug, and then picked my plate back up and walked back into the other room to eat. “You’re not staying?” my mom said. “Oh, come on,” my dad said. I didn’t know how to explain that the combination of the relentless overhead lights and the TV blaring at 100 (I am not kidding) and my mom barely eating and my dad so easily startled had caused me to begin weeping again, the result of being trapped in a bad movie that can only end after much more suffering to come.

I keep trying to find the humor in all this.

On Friday afternoon, around 4 PM, my parents, who had gone to bed at their usual time of 3 PM, were startled when they heard a knock at the back door of the playroom (their new bedroom-normal), and it was Justin the physical therapist. (On Wednesday, Justin had left before I could write down the time of his next visit (I was on a Zoom work call in the dining room), and my parents had said that there wouldn’t be another visit until next week.) To my surprise, my mom rallied, put on her nice wig, and went on the walks through the laundry room and kitchen, did the band stretches, made humorous comments. My brother and I, meanwhile, stayed stretched out and prone, Jeff on my mom’s lounge chair and I on the loveseat, watching Midsomer Murders. Justin came in with my dad to write his next visit on the calendar while I recorded that date in my phone, and I said to Justin, “I know that my brother and I look to you like geezers in our 50s, but inside we are just teenagers in our parents’ house.”

Oh, look. Found some humor.

I suppose that fact, of being a perpetual child, is why I don’t fully know how to be here, having also to do with the fact that on Saturday and Sunday, after her Friday late afternoon rally, my mom stayed in bed and barely moved except to walk on her walker to the bathroom a couple of times, and to sit up to nibble on what is probably at most 700 calories a day; I figure it’s closer to 500. I don’t know what to do, or how to get her and my dad to see that this starvation is why she is so tired. I just sound like a scold.

Not What It Used to Be

Calls from friends matter more than I would have imagined, like pictures of her baby grandson to my mother. I missed a call earlier this week from my friend Mark, a retired schoolteacher approaching age 80; I texted him; he texted back Sunday about a good time to call; I texted him that 7 PM would be a good time to call, and he called. (It’s all so complicated now, isn’t it?) He’d recently driven down from his home New Jersey to North Carolina to play piano for a former student’s wedding, and since he’d gone that far, he decided to continue down to South Carolina to visit a 92-year-old writing professor, a woman often described by the former director of the Bread Loaf School of English as “indefatigable.” But now Dixie tires easily, Mark said, though they had a very nice visit. The subject they found themselves coming back to, however, was not so nice: the deterioration of the place we all thrived in back in the 1980s and ’90s, Bread Loaf.

Unlike Mark and other friends, once I got my master’s degree in ’94 (and only returned in the summer of ’96 on an NEH grant for theater teachers, a return that made me know I was done with higher education), I had no real desire to visit. I like seeing people I love, but truth to tell, when I graduate an institution, I move on. Just as some Virginia Tech grads I knew became townies, some Bread Loafers returned to the Mountain, as we called it, in Ripton, Vermont, summer after summer to work there. I never felt that kind of attachment, though I dearly loved my time there.

The magic for me started with a brochure in my Appomattox P.O. box, one that showed a 30-ish blonde and bearded guy sitting on an Adirondack chair in a green meadow. The Bread Loaf School of English, located at the site of the famous Bread Loaf Writers Conference, boasted a wide array of classes, and required no thesis for its master’s program. In addition, the program only took place in the summers (five of them for a master’s) so that it could fulfill its mission to continue the education of working English teachers as well as writers. From the first arrival in my pickup truck (on my rural teacher scholarship, the big push I needed to apply in the first place), the creamy yellow-orange buildings with forest green trim, the meadow, the Green Mountains—all of it made me feel home. The added contraband view of electronics, including radios and televisions, and the discovery that there were no locks on the doors, made me weep with gratitude. A dining hall bell rang for the three very hearty meals each day, a room to sleep and study in, classes to attend, porches to sit on—all this and the ability to focus on growth instead of world worry was beyond a privilege. It was a lifeline for a Miss O’ that was a very lost soul at the time.

Over the years, as Mark went from Bread Loaf graduate (class of ’89) to administrative assistant (up until about 20 years ago, when his own parents required constant care) to regular visitor every August to play graduation, he has had to witness what feels to him like the deterioration of our beloved institution, degraded by the unavoidable advent of the personal laptop, personal printer, demand for internet access, and cellular service, and all the infrastructure updates these modern needs entailed. A change in administration brought a more hands-off, corporatized approach to the school, less benevolent parent who wants to see you thrive creatively, and more an efficient parent who makes sure you have clean shirts but otherwise keeps their distance. (Optional locks came to the doors my senior summer of ’94, when personal computers became more popular; permanent locks came about the following summer, after my time. I think of Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall,” wondering what we are walling/locking in or walling out.)

Metaphor Alert

The change to Bread Loaf from a kind of Brigadoon for teachers and literati became, as I talked to Mark, sort of analogous to the deterioration of my mom’s body; and the (understandable) lack of her hands-on nourishment of her children struck me as analogous to the (less understandable) demise of spiritual, personal, and creative nourishment at Bread Loaf and its former feeling of family and welcome and love of the human enterprises of reading, writing, and theater, of storytelling, of good talks, good walks, joy in nature, sunrises and sunsets, the heavy dewy mists after a late night of storytelling around the bonfire. We were there at a magical time, Mark and I agreed; were lucky to have been part of it when we were (though today’s students won’t know the difference, or what a difference of perspective they could be enjoying, given that there is no substantial shift from their everyday lives and the summer retreat, phones ever in hand). To continue this analogy, my mom moved from poverty to middle class prosperity; did better than her forebears but not without working for it; and there was a golden time, sort of, but that time is gone.

The big analogous questions: 1) Do I corporatize the care of my mom and dad? 2) Do I keep trying to force feed my mom? Finally, 3) Do I keep sending yearly donations to a corporatized Bread Loaf? Clearly these aren’t the same things, as for one, in my mom’s case she’s my mom, for crying out loud, and for now I remain on site; in the case of my school, it’s a place I’m not really responsible for, however much I’d like to help keep it going, though I haven’t been to Bread Loaf in 20 years and have no desire to see it again. Still, I want never to lose the feeling of deep connection and gratitude I have to both my upbringing and my education.

The analogy continues: just as the internet is never off now at Bread Loaf, the TV at I never off at my parents’ house. Like the internet for today’s generations, the television is for my parents their company, their connection to the world. It blares around 100 because of my dad’s hearing loss, so every conversation has to be had over the television; and by contrast, because of the radio silence, one witnesses very little in the way of conversation these days at Bread Loaf. With all this change, I guess, I get weepy, at moments, or get the shakes, not because of the inevitable (there is only one way this is going to end, after all) so much as that any possibility of preparing for it in anything like a meditative way is off the table.

There are other significant differences between my mom’s bodily changes and those of my beloved Bread Loaf. While I encountered the necessity of change at my parents’ house because of old age (an old age many don’t have the privilege of reaching or reaching in the relative comfort of their own home), Mark walked into the Bread Loaf community Barn this past summer, with its empty chairs, or one or two individual students sitting with a phone, no one in conversation, no one playing the piano; the snack bar for coffee and tea closed long ago, no fires lit in the fireplace, and no more dances there on Saturday nights, since people leave campus on the long weekends—no more Friday classes or planned weekend events, because the new administration, it seems, encourages people to get away. Fewer people to cook and clean for, I guess. That’s a choice the school made not because of an aged 100 years of the school’s existence, but because the human race appears to be done with bucolic life and the philosophical reflection that allows, at least for now.

I guess it’s an odd analogy, these two things, but it’s helping me think through change and luck and the necessity of moving on, of carving out a creative spiritual life despite or even because of this decay. Something has to rise from the noise and the ashes. Doesn’t it?

Sending love to all.

Miss O’