On character, tragic flaws, and hope

Nov 09, 2025

On November 9, 2010, 1st Lt. Robert M. Kelly, USMC, was killed in Afghanistan. Robert had been a student of mine at Gar-Field High School in Woodbridge, Virginia, along with his older brother, John, both of them the sons of Gen. John Kelly (Maj. Kelly, when I first knew him; I attended the ceremony when he became Col. Kelly). Both John and Robert were in the Drama Club, and very different kids, John doing technical theater (lighting), Robert hanging around until he scored a legendary turn as Juliet in The Complete Works of William Shakespeare Abridged (with a cast not of three but of thousands) his senior year, a performance that caused his father to laugh harder than I’d ever seen him do. Interestingly, son John (now a colonel in the USMC himself) was naturally funnier, but ironically it was Robert’s relative seriousness and deeply felt empathy that made him a great comic actor.

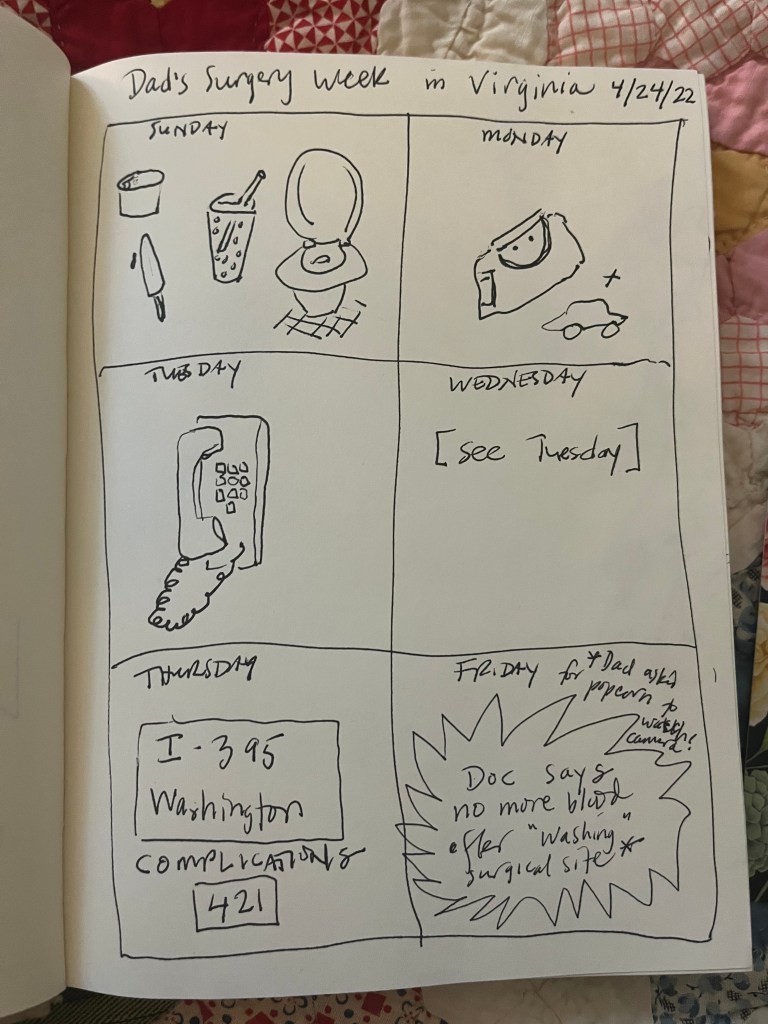

I got the news of Robert’s death 15 years ago through missed connections all day, brother John trying to reach me, my return calls back going to voicemail; I thought something might have happened to Alan, another former student and John’s best friend; finally I got hold of Alan while at a play lab at the Pythian on the Upper West Side, where cell reception as terrible and I had to go out to the street to reckon with the truth. I didn’t know Robert had even been deployed; apparently it was a sudden decision to send his unit over, and maybe only a week had passed since his arrival, an IED doing the job.

Robert’s funeral and burial at Arlington, just eleven years after his graduation, seven years after I’d left teaching and had moved to New York, was attended by well over a hundred people, many from Gar-Field, teachers, students, friends, parents, along with his family. Hard to process even now. I was reminded of all this yesterday when my friend and retired department chair Tom texted to remind me, thinking only ten years had gone by. (I knew it was longer because my cell phone had been a flip phone. Isn’t that a particularly millennial reason to remember a date?)

So tragedy is on the brain this morning.

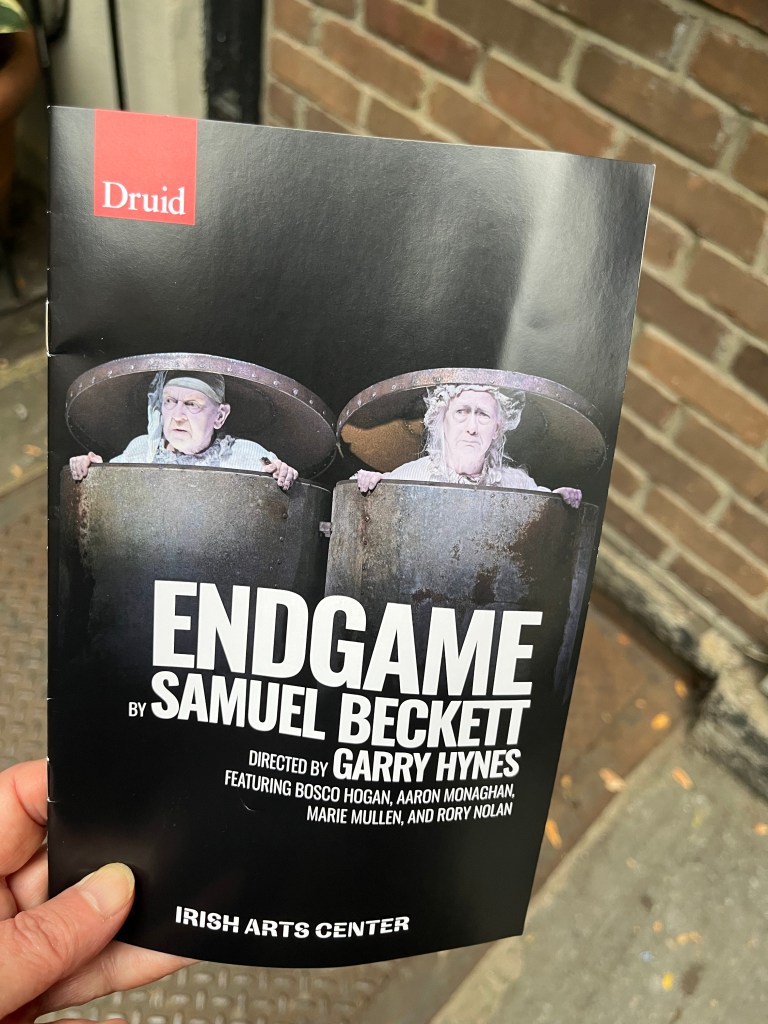

Last Saturday I went to see a West End-Broadway transfer production of Oedipus, a new adaptation and direction by Robert Icke (say Ike), with friends Frances and Jim, who got the tickets for us (or else I might have foolishly missed it). The lesson of Oedipus is, famously, “One always meets one’s fate in the path one takes to try to avoid it.” In the Greek version, the Oracle at Delphi prophesizes that the baby born to King Laius and Jocasta will one day kill his father and marry his mother; Jocasta then, to spare her son, orders her servant to kill the baby. Instead, the loving servant places the baby in the woods, where he is found by an older couple from the country who raise him as their own, no one the wiser. Until eighteen years go by…

In this update, Mark Strong plays Oedipus as a political candidate on the night of a highly consequential election (intimations of Trump v. Democracy), and all the action takes place during the two hours between polls closing and the announcement of the winner (a big clock on the stage counting down—Aristotle in Poetics says that any good drama should play out in no more nor less than two hours, and Icke takes on the challenge). In a filmed sequence as the show’s opening exposition, a confident, sexy Oedipus, standing outside what looks to be the British Parliament building, tells the press that he knows people question why he, a foreigner, should lead them, and he promises (without warning to anyone in his circle) to “release my birth certificate.” It brings up Obama, Mamdani, all the prejudices of our times, and if you know the story of Oedipus, it’s the perfect setup for an adaptation. (Icke must have shrieked and shaken with freakout when he thought of it—hoping no one else saw that obvious and genius connection up to now.)

Oedipus—handsome, smart, gifted, loving, and progressive—has one fatal flaw: hubris. He really believes he is in complete control, fully in possession of himself, knows who he is, knows who everyone is in his life. The next two hours unravel in the revelations we know from the Greek tragedy, all so believable and so timely, with Lesley Manville’s Jocasta ripping your heart out, her (updated for our more enlightened times, shades of Epstein) story of being raped by old Laius at 13, forced to give up the baby to die because he’s married; Laius later marrying her and leaving her a widow who later meets Oedipus, falls wildly in love, and marries him, giving him three children, she then in middle age. At the play’s opening, Oedipus is 52; Jocasta, we only later realize, is 65; their children are college age. In short order, despite a landslide victory, their children are about to lose everything, Jocasta her life, and the nation the promise of a brilliant leader. (The best part was sitting next to someone who didn’t know the story—lots of people don’t—and hearing the gasp.)

How does any brain process such a trauma? Frances and Jim and I staggered through the tourist minefield that is Times Square to the quiet of an Italian restaurant to process it, all of truly gutted, Aristotle’s catharsis manifest. In enduring tragedy, and in catharsis, we not only heal, we are cleansed.

This morning I watched a YouTube video sent by my friend Ryan last night of researcher and “No. 1 Brain Scientist” Jill Bolte Taylor in conversation with podcaster Steven Bartlett, talking about the “four characters” in our brain’s left and right hemispheres. As a result of a stroke at age 37 in 1996, Bolte Taylor’s Harvard-ladder academic career ended, and the next eight years were about recovering the functionality of her left hemisphere, the part of our brains that does numbers, controls language, helps us plan and think. During those eight years, she worked to use her right hemisphere to help her rebuild the cellular connections in the left, and the result was a huge new life focused on even deeper brain work while living on a boat and not in a lab, connected to nature and to the universe, using her whole brain. I highly recommend the video, which I watched at 4:30 this morning (because old), and her “four characters” of the brain put me in mind of not only all our society’s conflicts but also of all the characters necessary to have an effective drama:

1. Character One: Left side, thinking: the planner, analyzer, counter, linguist

2. Character Two: Left side, emotional: the grudge holder, trauma re-liver, pain protector

3. Character Three: Right side, emotional: the explorer, the curious one, the playful one

4. Character Four: Right side, thinking: the connector of experiences, keeper of wisdom

Just as a drama needs all these characters for conflict and resolution (my take), humans need all four in balance to be whole. I took loads of notes, and if you watch the video, you can too, but Bolte Taylor’s message of a society out of balance resonated most with me. Most of our lives seem to be spent lived only on the Left side, she says, holding grudges and reliving trauma as we strive for perfection and knock ourselves out to make money. It’s killing our brain cells, it’s killing us individually, and it’s killing the planet.

To wit: Sec. of Defense (he says “War” but it’s not official) Pete Hegseth announced this week that the United States is no longer a peace-seeking nation, but rather, our military preparation will be solely focused on wars. We know from Republican spokespeople, such as Russell Vought, JD Vance, and Elon Musk, that “empathy is weakness” (a negation of the brain’s right hemisphere) is a guiding principle for their politics. The Conservative Movement is totally, then, left-hemisphere in the brain, focused on self-interest, self-protection, generational trauma on a tape loop. It’s not sustainable, but it has to be gotten through and past, somehow.

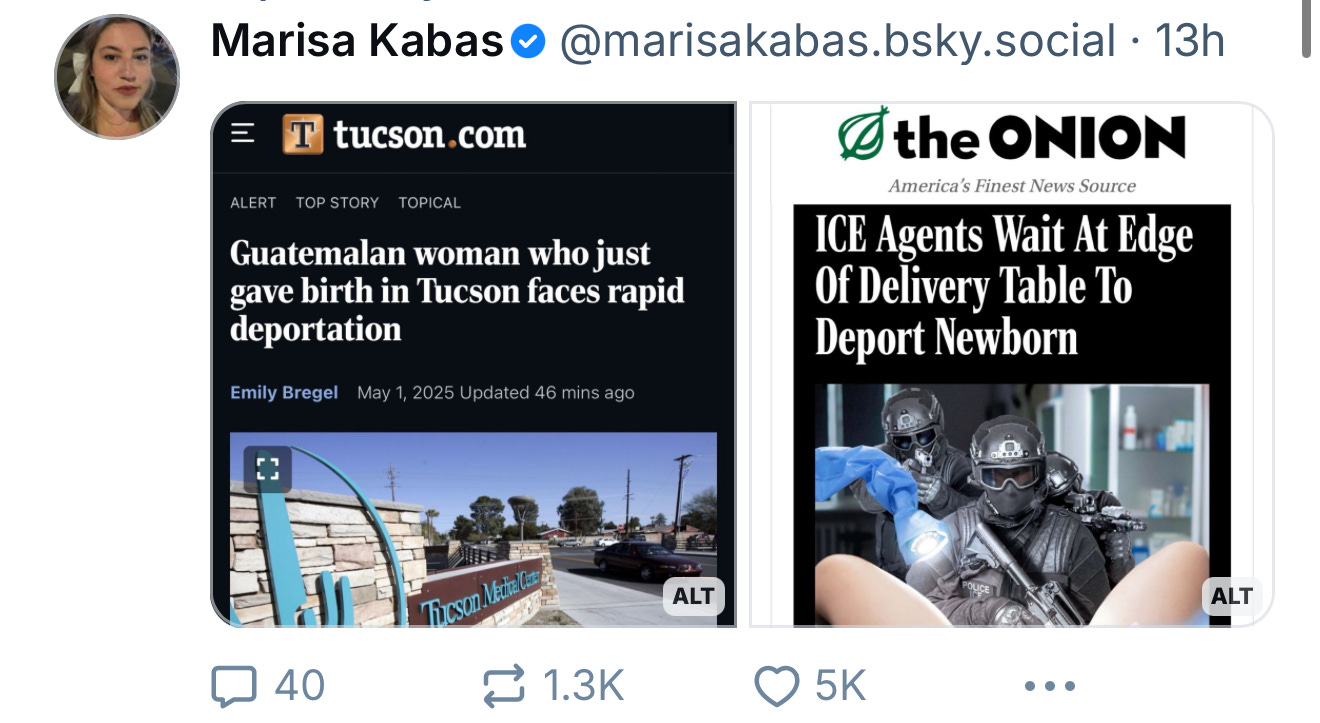

What I think Conservatives fear most about education, about learning the truth about our history, is what the play Oedipus shows so shockingly: when you uncover the truth about yourself, you are destined for destruction. But what the audience learns is that no life is an honest life if it’s built on lies, when your armor is a birth certificate and the woman who raised you as your mother, and lied about it, thinks it’s “only paper.” And I’m struck by all these paradoxes—the fear we have of knowing the truth, and yet the impossibility of living an honest, full, happy life without it.

As your Miss O’ has long said, if your belief system cannot withstand challenges to the point that your response is to stifle and even kill to stop those challenges, you don’t have a belief system—you only have fear.

What Oedipus lacks is balance—for him, in his ignorance, life has been pretty great. He is empathetic but only intellectually. (I think this same hubris applies to a lot of America’s Liberals, if I’m honest.) Oedipus’s mistake, his hubris, was to be blindly fearless, blindly on the side of the common man (because he was raised by fine, working class parents) without knowing his own life’s truth—he was the product of rape by a lecherous pedophile of a king, and he married his own mother because of the coverup. At the end of the play, Oedipus blinds himself, and as the cult-prophet Teiresias tells him, when you learn, you will go blind; and when you are blind, you will see properly.

In a similar way, Jill Bolte Taylor’s stroke—the near-total collapse of the brain of a preeminent brain scientist—made her work expand into realms she could not have imagined during her eight years of recovery.

And this all got me thinking again:

We have to release the Epstein files. Virginia Giuffre’s death cannot be in vain.

We have to embrace our nation’s original sin, slavery, teach it properly, reckon with it, so our nation can progress in smarter, healthier ways.

We must demand the resignation of Pete Hegseth, and work to be a peaceable nation, so that there are no more 1st Lt. Robert Kellys dying on foreign soil; and you’ll pardon me for not grieving Dick Cheney.

This is a heavy lot for a Sunday morning.

I’m sitting here on this November day, in my kitchen rocker, worried again about whether or not I need a new refrigerator (thermostat being weird) and a new Mac (battery not fully charging), seeing it’s after 9 AM and I really need to dress and go out and about before it rains. And these mundanities of life require our attention, our presence, to live fully, ever balanced against all those huge mega truths.

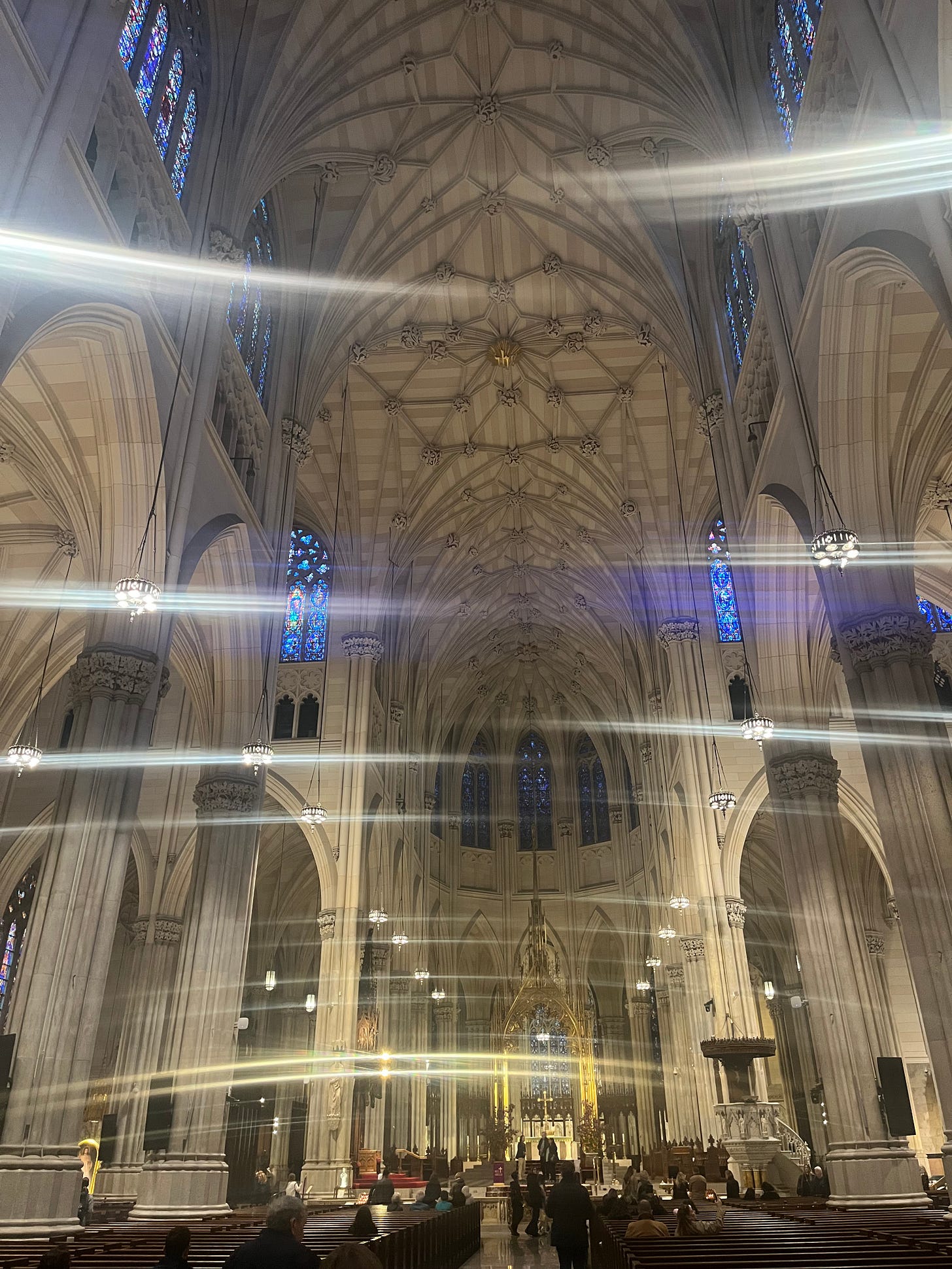

On my personal day on Friday, I found myself in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue, lighting candles (one for my mom, one for my friend Richard’s mom, and a third for the ancestors), which I hope was not hypocritical from irreligious me. It was nice to sit and meditate in the midst of the most famous cathedral in the biggest city with the most consequential mayoral election perhaps ever, and be present to my mom and memory.

Sending love and balance,

Miss O’