The title of Marcel Proust’s famous novel, À la recherche du temps perdu, was beautifully translated as Remembrance of Things Past, until some literal-minded academic pointed out that the literal translation, the actual title, taking it word by French word, was In Search of Lost Time. And I say, Is it? Which novel would you take down off the shelf? Exactly. Sometimes literal is not the way to go; sometimes essence gets more at meaning. Today I’m all about memory.

Yesterday I went to see Marjorie Prime at the Helen Hayes Theater on W. 44th St. here in New York. The play has been around since before Covid—my friend Colleen auditioned for it when it was starting a run at Playwrights Horizons, where our playwright friend Tom saw it. That’s how they remember it—an event before Covid. The play itself, by Jordan Harrison, concerns an 85-year-old woman (born in 1977, so we’re about forty years into the future) in the late beginnings of dementia, cared for by an unseen woman named Julia, and visited periodically by her daughter and son-in-law. At the opening, an oddly stiff, handsome young man (Christopher Lowell) is talking with Marjorie (96-year-old June Squibb, who is just remarkable; I first became aware of Squibb in the movie About Schmidt, where she played a Midwestern wife to Jack Nicholson’s Schmidt and was so good I thought they’d plucked an Iowa housewife off the street for the brief but pivotal part. Sidebar: I know he was nominated for an Oscar, but I thought Nicholson was all wrong for the part—it’s one that really belonged to a less complicated actor like Paul Dooley. I digress—and yet remembering our takes on things is also part of what I’m focused on this morning.)

To keep her mother company, Marjorie’s daughter and son-in-law (Cynthia Nixon and Danny Burstein) have purchased her a Prime, an android, this one in the form of Majorie’s husband, Walter, when he was young (as she requested)—so the oddly stiff companion is stiff for a reason. A Prime can be generated into any form, to be filled with whatever memories people give it; as a result it can converse by speaking only in programmed memories and saying comforting things. The play is asking us to consider what a person is. Is our worth, our existence, dependent on what we can remember, even in facsimile, and must what we remember be in terms of other people in our lives? Should trauma remain part of our memory? When we can’t stop remembering trauma, is therapy or forgetting harder the better way? What does it mean to truly live? Ultimately, Are we only what we can remember and who remembers us? For a relatively spare play, it does bring stuff up.

I found myself this morning asking, “Why do we remember?” And more than that, is memory the essence of humanity? It’s the first day of Black History Month, and I think of Alex Haley’s historical novel, Roots: The Saga of an American Family (1976), where Alex learns about his enslaved ancestor Kunta Kinte (his name and story passed through Haley’s family over generations), when in his research Alex travels to West Africa by the Gambian River and finds a griot, a storyteller who tells the history of all the people of a village, committed to memory, once a year, and it can take up to three days without stopping to do this. But when he hears “Kunta Kinte,” and learns of his capture by slave traders, Alex knows he’s found the complete history of his people, almost unheard of for African Americans (even finding the affirmative mark of a slave on a slave schedule, let alone the name of the ship, let alone the name of the African, as I’ve learned from Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and his PBS series Finding Your Roots, is beyond rare).

In 1977, when I was 12, ABC showed Roots, a miniseries based on the novel, that galvanized the whole nation (there being only three major networks and no cable), teaching white America about real enslavement for the first time. To quickly erase (again) that powerful, historically true narrative, NBC countered by showing Gone with the Wind on television for the first time (the “television event of a generation!”), so we could (mis)remember the real story, the glory we lost, I guess. Horrifying when you think about it. And here we are. (I remember my social studies and English teacher Miss Covington glossing past Roots and gushing about Gone with the Wind, her favorite movie, telling us the whole plot—and keep in mind she (no more than 30) could only have seen this 1939 movie once, or twice at most, in a revival at a movie theater, say, this being before VHS, let alone streaming; when she taught us about the Civil War, she minced no words: the North didn’t want slavery, but they didn’t want Black people there, either. I cannot imagine what the Black kids in her classes felt.)

Thinking more about ethnic generational memory, I remember seeing a David Mamet play maybe 25 years ago, The Old Neighborhood, where a Jewish man named Bobby Gould (played by Peter Riegert, who should have won a special Tony for his master class in active listening) who in three scenes visits 1) a childhood friend; 2) his sister; and 3) an old girlfriend. In each scene he says a few words at most, and listens to each of the others talk about the past, the “old neighborhood,” partly a shared history, partly revelations about things he didn’t know. While the play massively bored the three friends I was with, I found it galvanizing—the terrific performances (Patti LuPone played the sister), yes, but mainly the premise, that so much of our time spent with family and friends is absorbed in reviewing the past, our memories. Why is that? Why do we do that? What do we gain, or lose, from that act? In the first scene, Riegert’s character is visiting a childhood friend back in the city, staying at a hotel on a business trip. His buddy reflects at one point, “I could have made it in the camps,” and Riegert says, “You can’t know that,” and the friend insists he could. And that was the first time I became aware of the weight that Jews today carry when they had family die in the Holocaust.

Roots was the first time I had been shown anything about slavery, having grown up with text books that minimized the abuses of enslavement, and in a state with a state song, “Carry Me Back to Ole Virginny,” which says, “There’s where this old darkey’s heart am long’d to go.” (It’s credited to an African American minstrel, James Bland (1878), but its roots appear to go back to the 1840s, lyrics by Edward Christy and sung by Confederate soldiers; and in either case, yikes. It was not retired as Virginia’s state song until 1997.) In other words, the truth and memory of enslavement was not part of my white Virginia memory, so here I am in my sixties only now really reckoning with it, what with the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act passed during my first year on earth, a seeming ]course correction. Wow have I been blind.

What am I on about? History—the importance of a shared and factually accurate history, one we learn all our lives, together as a people, revised and reflected upon rationally as new information comes to light. National, personal—all the history defines us. I saw a post by a Black woman—and I didn’t save it and I hate myself—who pointed out that in her view the core issue for white people is that whites have no home. Blacks have Africa and enslavement to root them; Native Americans are the indigenous people. But whites? A culture of constant colonization and conquest, from ancient Rome to the Nordic invasions all over what is now Europe, most whites, especially white Americans, have no real homeland (this term tied to Nazis and white supremacists features on MAGA propaganda posters to bolster their deeply false and hideous American narrative). Everything for whites has been about invasion, genocide, rich man-enforced patriarchal “Christianity,” and repression of The Other to the point that we, as whites, have no roots and no shared memory beyond war and domination and fear. We whites have been trained by the rich elites to stew in hatred or resentment, say, crying on about our disrespected primacy; or, by contrast (it seems to me), we whites may live in bland acceptance of our privilege exercising little agency beyond voting and saving for retirement. How can you root in that?

So after watching Marjorie Prime, where the only value the characters seemed to place on one another was in memory—forcing one shared memory while maintaining the repression of another one, both confining—I got to thinking about memory as a kind of cage, its relation to creativity and forward motion coming into question. The white people in that play were defined by, and at home in, the past, but a murky, unsettling past, often manipulated and limited through the use of the Prime by the stories it repeated, with no clear plans for, or authentic excitement over, a present or a future. Is traveling to Madagascar the answer? (No.) At one point, the son-in-law replaces a dying Ficus tree in the house with another Ficus tree that no one pays attention to, and how is that a useful creative act? He’s the only character trying to reintroduce life into a dead space, and futile though it is, he at least is trying.

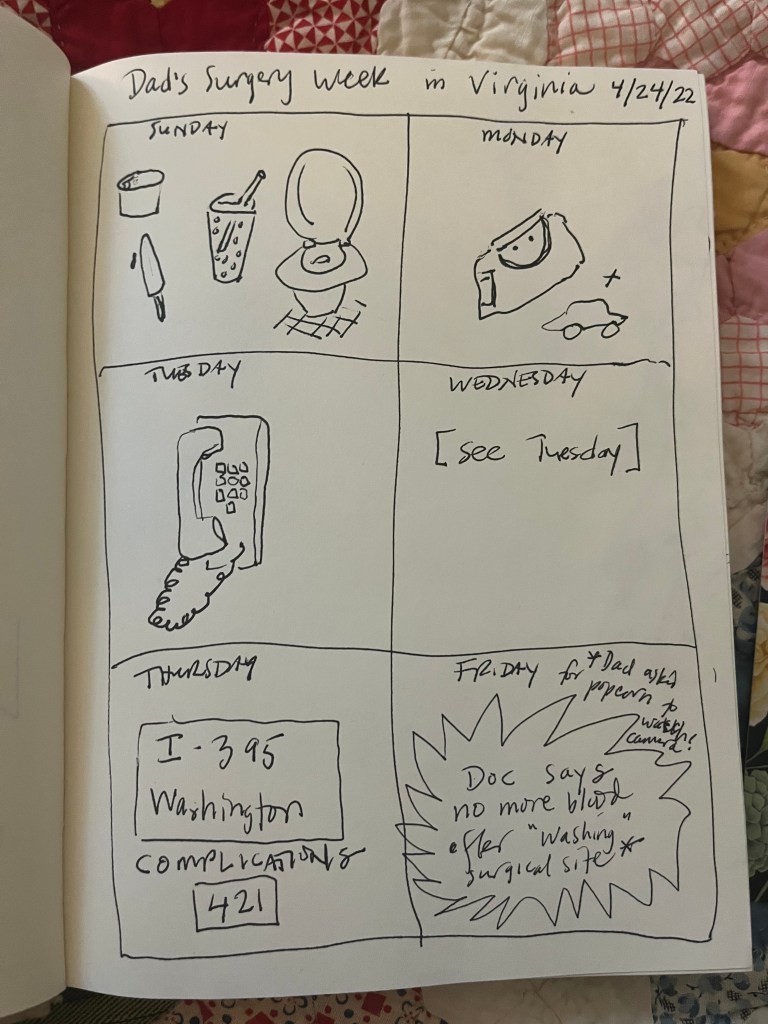

Some of the last things I did with my mom, Lynne, involved me asking questions of her life and filming her in very short videos; collecting recipes; she and I sorting a box of linen for me to take, tatting done by her aunt and grandmother. Memories through things, new stories emerging using the objects as a prime. And if we aren’t maintaining and deepening connections to our loved ones and our history, who even are we in the world?

When I look at Minnesotans and their powerful resistance to authoritarian rule, I am struck by this happening collectively and also in winter. Garrison Keillor used to begin his weekly Lake Wobegon monologues on NPR’s A Prairie Home Companion, based in St. Paul, Minnesota, “It’s been a quiet week up in Lake Wobegon, my home town out on the edge of the prairie. It’s been cold this last week.” That natural bond between Minnesotans in their landscape was ever and remains the relentless cold, the snow and ice (followed by the muddy springs, hot summers, and the short growing season). Anyone who is brave enough to move from Europe, let alone Somalia, to that unforgiving winterscape would need good neighbors immediately; and it’s that culture that appears to have bound all these people to one another—winter warriors—in an essential goodness and clarity.

My sibling text thread all week has been filled with photos of snow, including a video of my Virginia brother Jeff walking on top of snow, so thick is the ice still.

Virginia just set a record for the most days in a row below freezing—a totally unnatural thing, so yes, Herr President, this is a result of global warming—and I’m thinking that it’s winter above all seasons that makes us reassess, remember, and also be present. Winter is never boring, even if it’s exhausting. Winter does not forgive. You can never let up, chopping wood or shoveling snow or suiting up to keep warm. Sometimes you have to wait for the melt. But waiting is for the old, the Marjorie Primes of the world, and only then if they are looked after. The rest of us still have to get to work.

It’s history, people. It’s all about history. Let’s never forget this time, whatever happens, wherever we go from here.

And celebrate Black History Month. Learn all you can. As the snow deepens, as ICE expands, deepen and expand yourself.