Woolf works to guide us

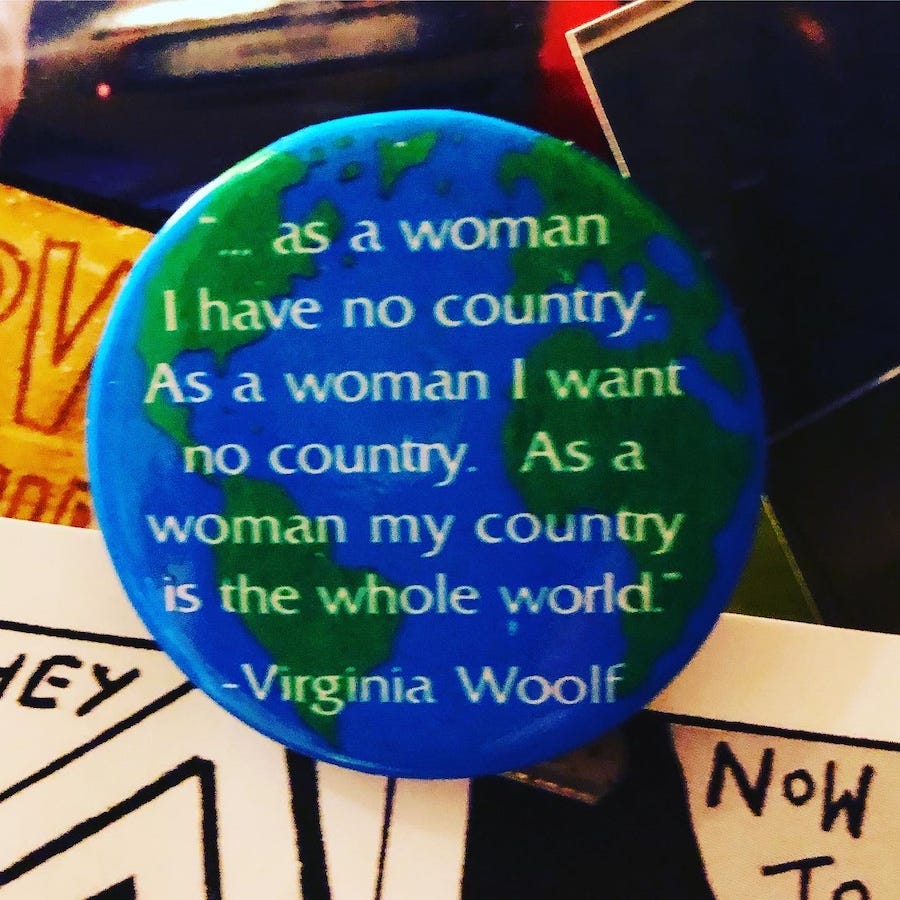

In the late years of her life, ca. 1936-1938, writer Virginia Woolf was experimenting with a text that combined the novel form with the essay form. The result was, in the end, two books, the novel The Years (which began its life as The Pargiters), and the essay Three Guineas. I’ve read many of Woolf’s novels half a dozen times each—Mrs. Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, the Waves, Orlando—I’ve even read Flush twice (the biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s dog, and it’s hilarious). I’ve read Jacob’s Room three times, I think, but the first time was the best, and Between the Acts at least twice; and the essay A Room of One’s Own I think four times through—I just finished it again recently and I think I finally got it all. It only took me 40 years.

Curiously, I have read her first two novels, The Voyage Out and Night and Day only once—they aren’t that interesting, though I might change my mind. The same goes for the The Years (though, ironically and not surprisingly, as it was a straight family chronicle, it was Woolf’s best selling book). I’ve also read Three Guineas only once think—all of that at Oxford in 1992, when I studied Woolf as part of my master’s. Be impressed. (I’ve also read her short fiction, only “Kew Gardens” and “The Mark on the Wall” standing out in memory.)

I have a brilliant writer friend who thinks Woolf writes the worst fiction known to man. I could not disagree more. But this same writer does not disagree with me that Virginia Woolf had one of the finest minds of the 20th century, and I’d say any century. As I’ve probably told you, for me Virginia Woolf renders the world precisely the way I experience it. Do with that what you will.

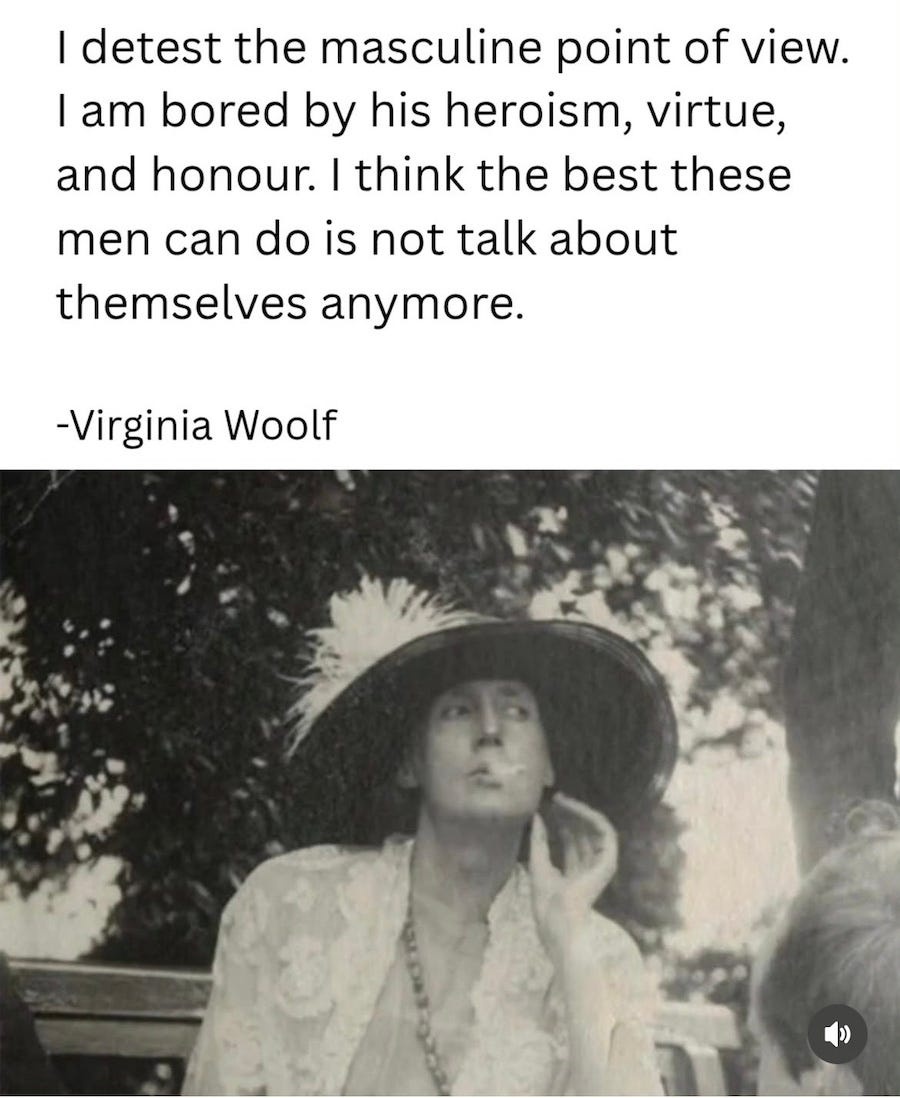

Today I ran across this post from HistoryCoolKids on Instagram, and it made me recall how important her pacifist essay Three Guineas (1938) is in the Woolf pantheon—that’s the essay the post refers to—and also how aware Woolf was that men are fucking everything up (this was around the beginning of the next great world war, England once again at the center):

The post text:

Teaching my Oxford class was tutor Jeri Johnson, herself a James Joyce scholar who for only that one summer taught both Joyce and Woolf (in separate courses); curious as to why she would be drawn to such polar opposite modernist writers, I did some research, in the time before Google, availing myself of the school library where I was teaching, and saw quickly that the writers were exact contemporaries, 1882-1941. How about that? (Note: if you want to blow away a professor, show up with a little tidbit like that and set the stage for your A.) I also learned that Woolf detested Joyce’s Ulysses, finding it vulgar (she’s not wrong, what with all the mentions of snot, for example, and masturbation); and the most important thing about Joyce’s book for me is that it inspired Woolf to write Mrs. Dalloway in answer: one day in a life in London, a woman’s life, in response to one day in the life of a man in Dublin. Both texts have richness, but Woolf’s is not designed to keep scholars arguing for a century, and that alone speaks to her quote up there.

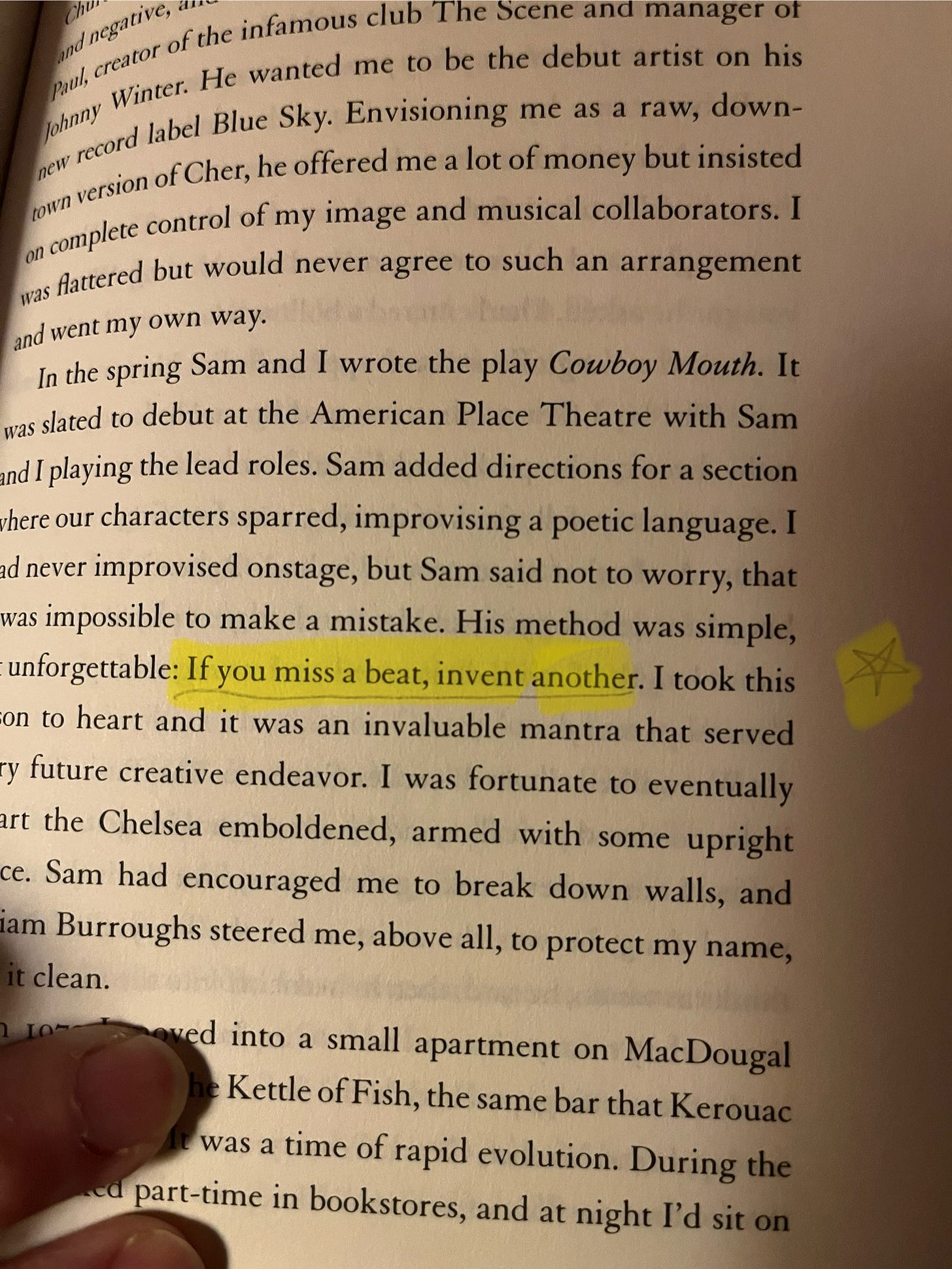

When Jeri assigned Three Guineas to read, I entered class the next day filled with ideas, bookmarked pages, notes in the margins. The essay’s premise is that Woolf has been asked for three guineas (pounds) to give in donation, one guinea each per charity, and she’s deciding which cause deserves her money. In the course of essay, she arrives at the conclusion that her final guinea can never go to supporting men taking us to war. My four classmates (this being an Oxford-style tutorial affair), all women, declared the essay a failure and Woolf a “shrill” woman. I sat in silence. They went on about how “now was not the time to call for peace,” “Hitler on the rise,” etc. They were utterly dismissive, and all discussion was shut down. Jeri looked at me.

“Lisa,” she said, “you’ve been awfully quiet.” I looked up and stated, “I loved it.” Jeri started to smile, and thus encouraged, I went into my rapture: “This is a woman who knows she doesn’t have a lot of time…” and I began flipping to my bookmarks and reading my evidence. As I type this for you, I can feel myself in that little Oxford office, aged 26, sitting on the floor, speaking with a young woman’s ardor. No one else said anything. Class was over, Jeri assigned us something, and I was the last to file out. “Thank you,” she said, quietly. “You’re welcome,” I said, and left feeling that I’d found my own way and stood my ground intellectually for the first time in my academic life. That’s pretty cool.

We are living in an age where the lies of men, the vulgarities of men, the warmongering and whore mongering and shit-peddling of men must finally end, or we all go down and forever.

This evening I’m embarking on a reread of both The Years and Three Guineas, because the mind of Woolf ca. 1936, when she began her work—seeing the writing on the wall in Germany—reminds me of myself and my female friends in 2026. Nearly a century on, men are still running and fucking up everything. I need fortification. We don’t have a lot of time.

Should you wish to start your own Woolf journey, as I think I’ve mentioned before, I recommend Mrs. Dalloway or Orlando—definitely not To the Lighthouse or The Waves; though I think they really are her masterpieces, it’s so hard to see why without a little primer. I speak from experience, take it or leave it.

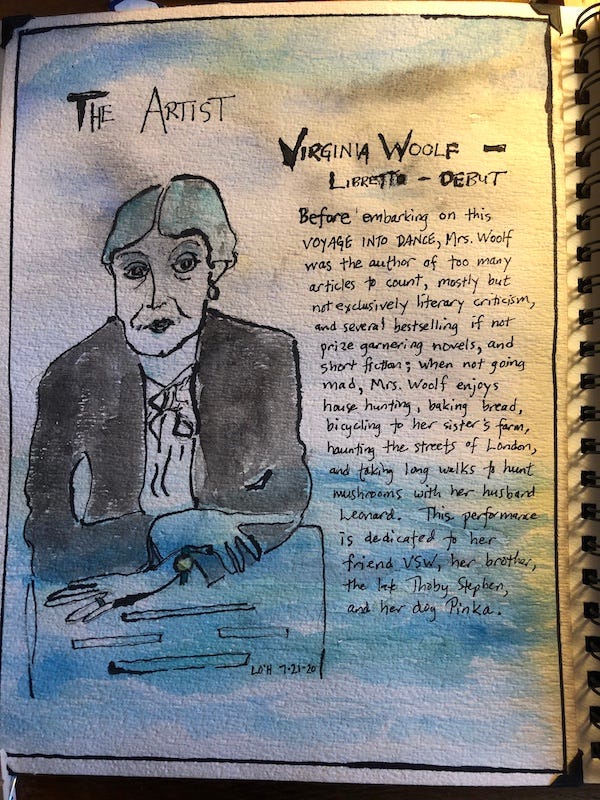

Woolf continues to inspire. The composer Max Richter and choreographer Wayne MacGregor created Woolf Works, which I saw on video during Covid from The Royal Ballet in Britain, and live in 2024 in New York. The only one of the three ballets that really works is based on Mrs. Dalloway, and I mention this because I’d love to see what women artists would do with the same material. You know. (I made this watercolor to show my friends who recommended the piece:)

Sending you love and Woolf inspiration as antidote to all the maleness madness. Let me know how you get on.