A millimeter matters

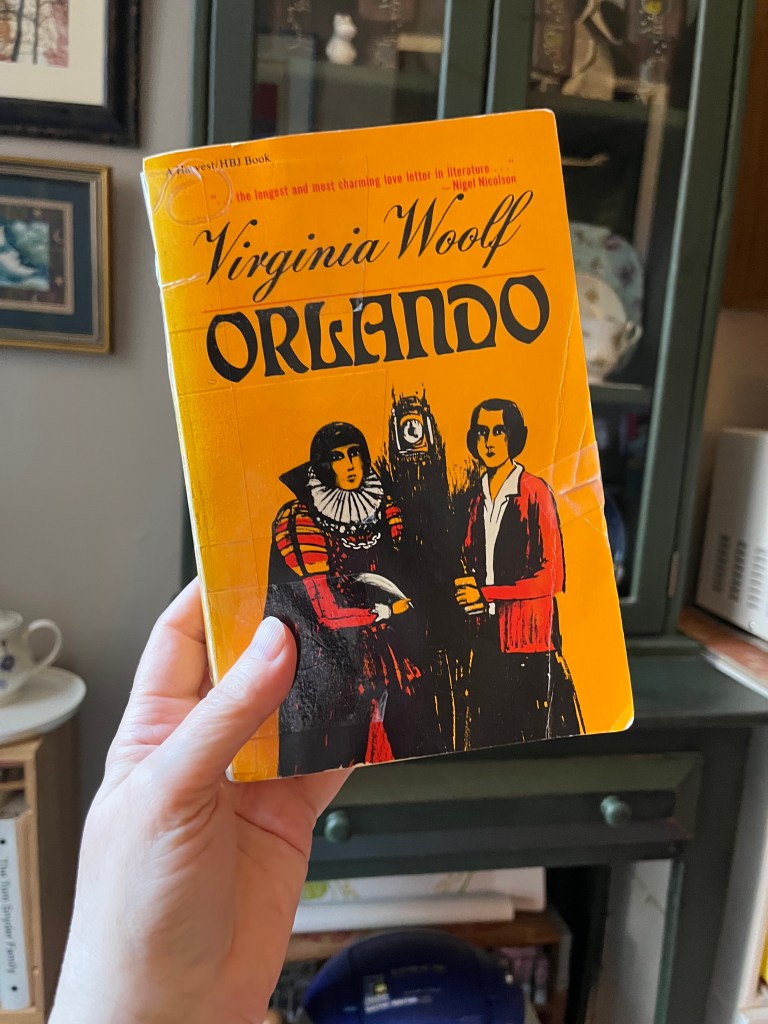

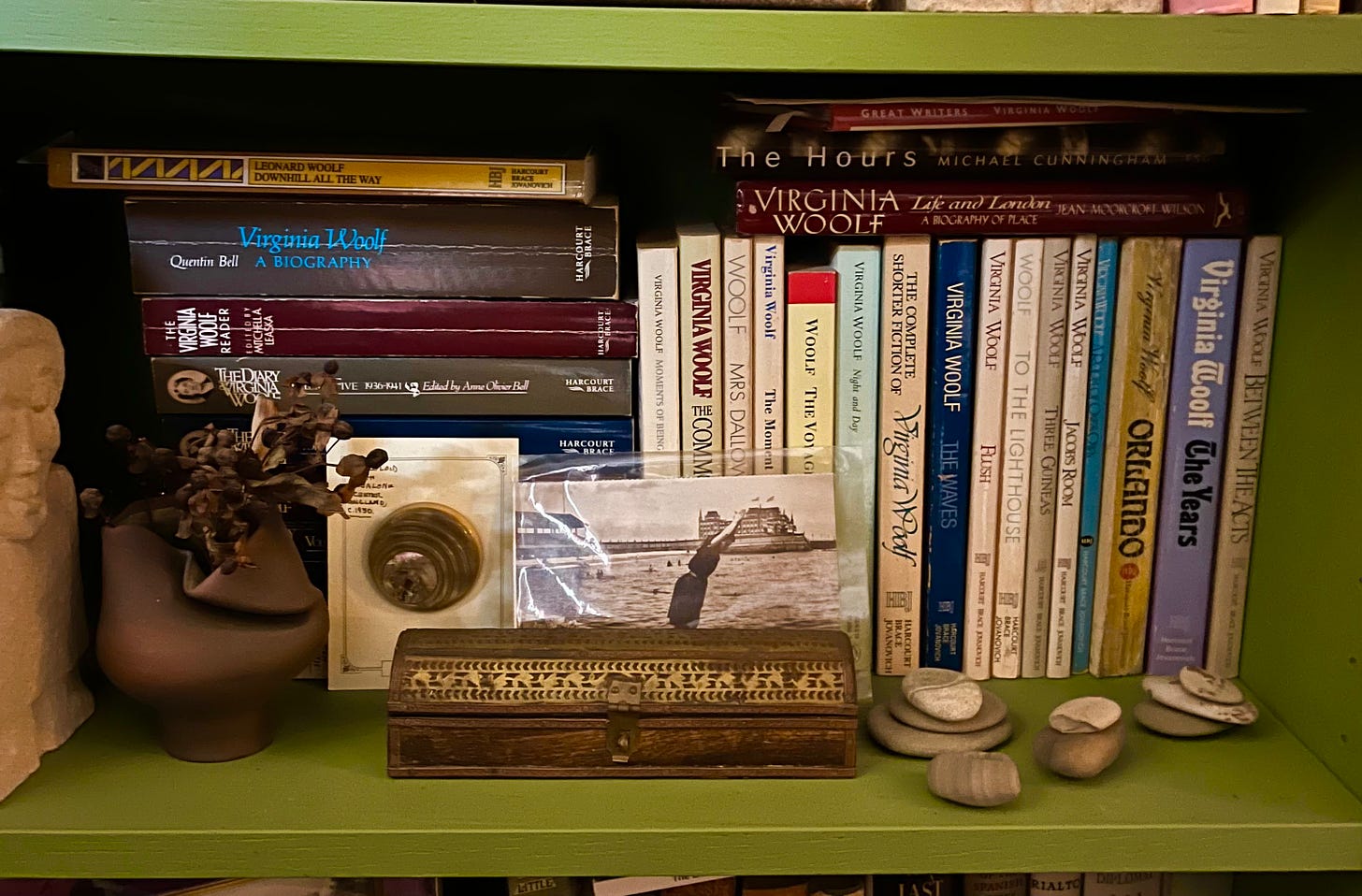

I just want to say that the luxury of owning a personal library is that not only do I feel cozy all the time, but I get to take evening tours and pick out volumes for bedtime reading. (Growing up, the O’Hara kids were about the only kids in the neighborhood with family bookcases, thanks to our mom, Lynne, having college textbooks, novels, and antique books to display and read.) Even now my number of volumes surprises some people, but I think, who wouldn’t want books around them? They are my closest friends. I saw an interview with Nora Ephron who said everyone asked of her family, “What are you doing with all these books?” (We live in a country like that now.) There’s no reason to finish a volume I peruse, or even read straight through. Sometimes I do that, but many times I just open a chapter and see what it says. If it’s not speaking to me, I flip around. Try another book. Like literary cocktails. It’s fun. This week I’ve been seriously rereading Finishing the Hat, Stephen Sondheim’s first volume of lyrics from his shows, 1953-1981, and so far I’m sticking with it.

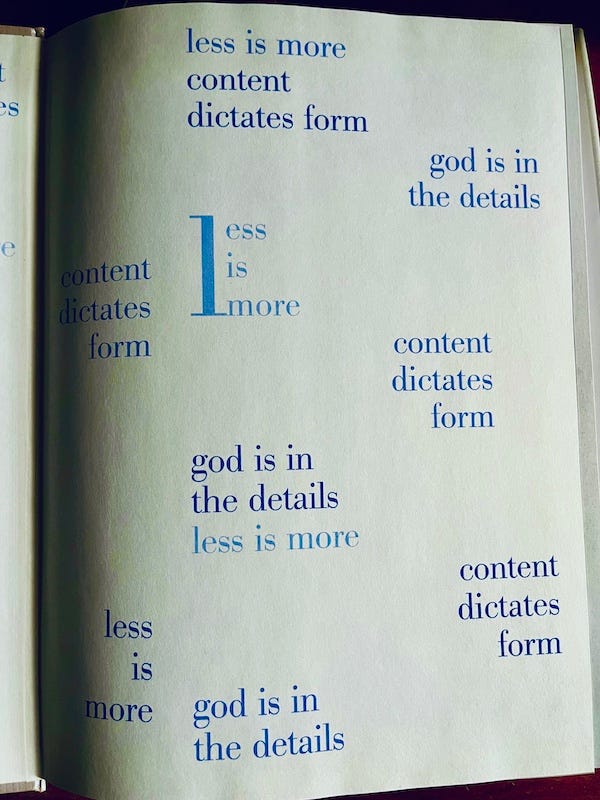

When Stephen Sondheim died in 2021, I felt as if I’d lost a friend. Though I wasn’t sure how I felt about his work for a long time, you must know that the key to falling in love with a theater writer or composer is seeing the work, and in a splendid production. It really changes everything. He had three principles that guided his life’s work:

“God is in the details.”

“Less is more.”

“Content dictates form.”

I love that Stephen himself admittedly didn’t always follow them, but we give ourselves a little grace; nobody is perfect. And he himself had favorite lyrics that other people don’t seem to care for. He endured his share of flops and lousy reviews. And he just kept going. Thank god.

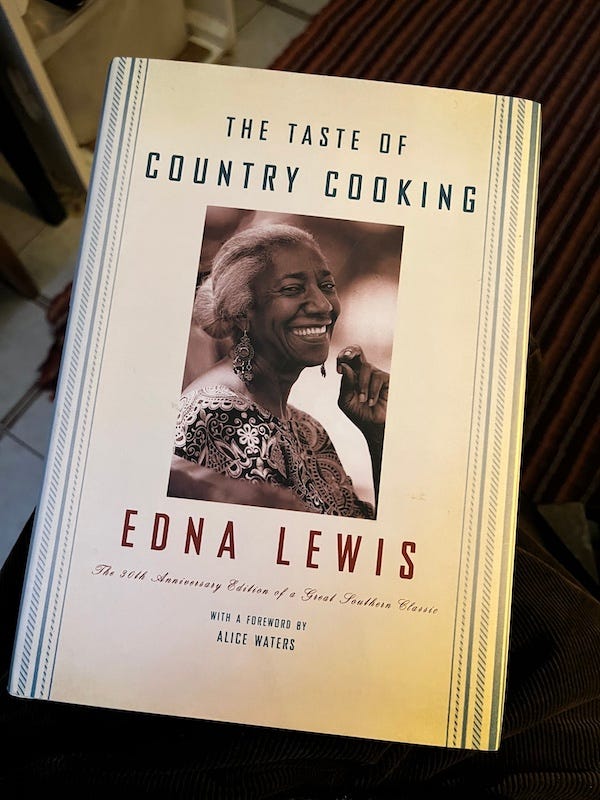

In an interesting coincidence, though sometimes I think it’s a bit more divine than that, these associative adventures, I’m also trolling PBS (while we have it) for documentaries and happened on two short ones. First, Marguerite: From the Bauhaus to Pond Farm about master potter Marguerite Wildenhain who, along with her husband, escaped the Nazis and made her way to California to teach pottery; and second, Finding Edna Lewis, about famed chef of 1950s Café Nicholas on E. 53rd St., cookbook author, and unsung mother of the farm-to-table movement, Edna Lewis.

And you might night think that Stephen Sondheim, Marguerite Wildenhain, and Edna Lewis couldn’t have much if anything in common, but you know what? God is in the details. Buckle up.

I’m not really going to recap all their work. But those rules up there apply.

“God is in the details.” Marguerite’s great contribution to many potters was, according to one student, “teaching us how to see.” For example, she’d have each potter make ten or twelve of the exact same pitcher or vase (since potters usually mass produce their work). The student would line them up on a board, and Marguerite of Pond Farm would walk and look and say, of maybe the third one, “This is good,” and of the eighth one, “This is good.” To the student they looked identical. Then she would point out a millimeter of difference in the rim, or the handle, the difference between being beautiful and merely serviceable (I think of the human face). God is in the details. It changed everything for students. (I’m obsessed by details when I direct a show, but not so much when I write, because I’m not an artist when I write.)

“Less is more.” Chef Edna Lewis grew up in Freetown, Virginia. In the Great Migration that took her to New York, she made a living cooking for artists, and word of her home cooking spread. She became an accidental star chef when she partnered (silently, as a Black woman) with two gay men to open Café Nicholas on E. 53rd Street, creating wonderful Southern cooking for writers like Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, and Gore Vidal. Lewis believed that food should be seasonal and that the ingredients should speak for themselves. Nothing should be overly prepared, overly seasoned, or fancy. You might call it simple home cooking except that her dishes were both gorgeous and delicious, prepared by someone who knew what she was about.

“Content dictates form.” In the theater, the writing and the intent dictate whether something is a play or musical; or whether it’s theater at all. In pottery, the intended use of the vessel dictates the size and shape. In cooking, the ingredients at hand dictate the kind of meal it will be. I’ve been mulling that principle over, and not to get all metaphorical or analogous, but I have to go a little political here. Content (greedy, sociopathic, ignorant bastards) dictates (!) form (evil shit show).

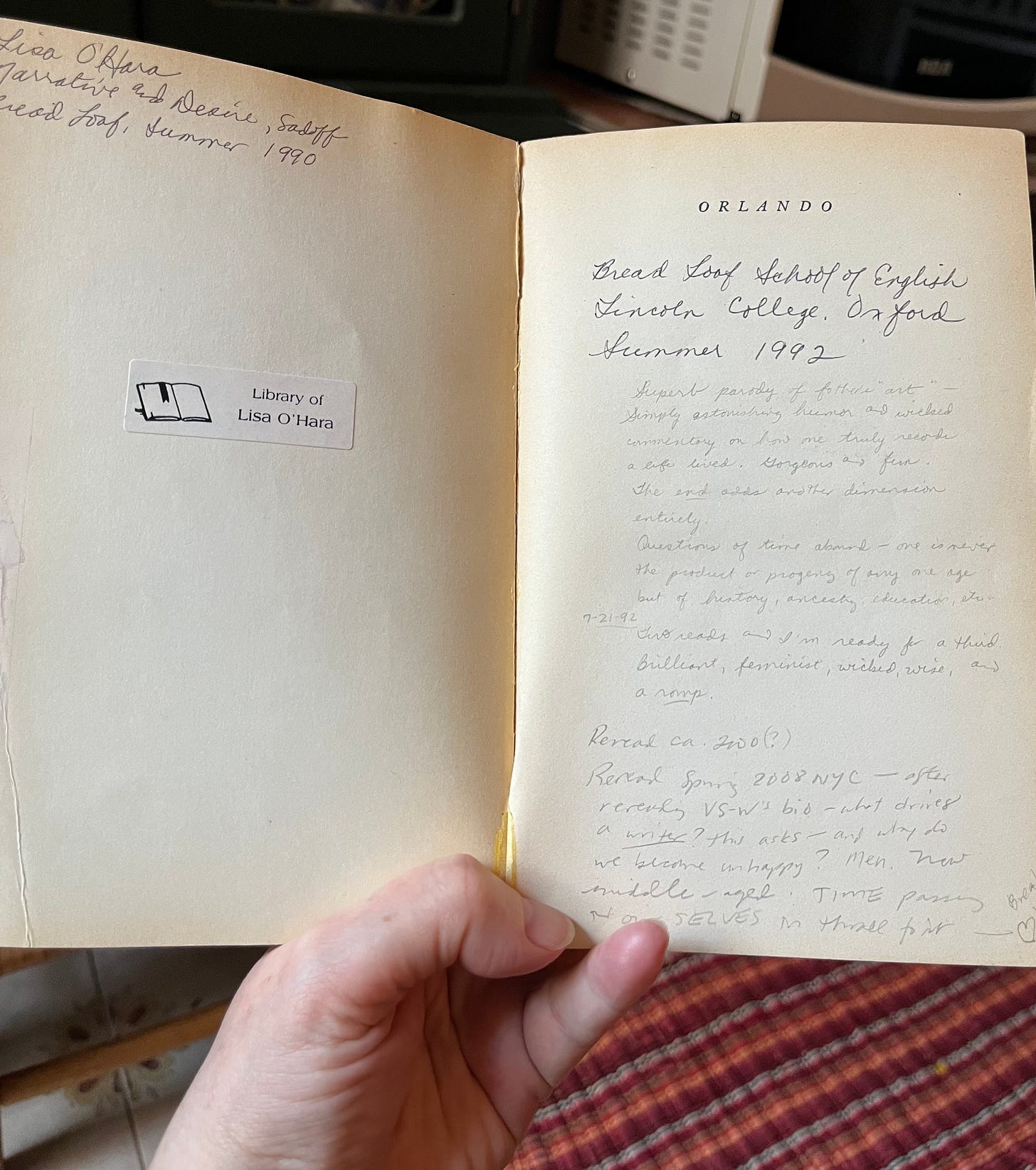

Speaking for myself, I wish I had the talent to be a playwright or a novelist or a poet. I haven’t done theater in years because it’s a collaborative art (it’s not like I can walk around my apartment and “direct”), and collaborating is something I never have time to figure out. But for whatever reason, ever since I was a kid and started writing, I’ve felt I had an obligation to study news events, internalize them, and interpret them for everyone. I don’t enjoy it, necessarily, and will never make a living at it, but I can’t seem to help myself. When asked in high school by the “gifted and talented” program advisor, Mrs. Hubbard, why I kept a journal, I told her I saw myself as a chronicler of my time. She snorted disdain. Years later, when I related that anecdote to my first professor at the Bread Loaf School of English (a summer master’s program designed for teachers), Prof. Cazden snorted almost identically. It was uncanny.

Somewhere in our lives, no doubt, we’ve been made to feel less than. (Both teachers (graduates of Bryn Mawr and Radcliff, respectively) told me without apology, one overtly, the other hoping I’d take her meaning, that I just wasn’t smart enough to be there, whatever that meant. It’s not like I was stupid, exactly, but it’s annoying for brilliant educators like them, I guess, to be around the merely bright when there are geniuses to teach. You know how it is. My response was to say nothing, and my revenge was, I stayed and decided to belong. I really learned a lot. And it all worked out, because as it turns out, they were wrong. Never let them tell you not to dream.)

And so it is that, to this day, I keep feeling this pull to chronicle my times, though to what end I don’t know. I’m not smart enough to solve much—my teachers weren’t wrong about me not being a genius—but you can’t do nothing, in times like these. (Chuck Schumer, is this on?) I try to chronicle what I see and still hold on to the world I want to live in, the world I want us to build. First, obviously, it involves shipping all these the MAGA Nazis from their demented reality show, White House USA, to some tropical island where they live in golden mansions and go on staged hunts with all the guns of their wet dreams and watch all the porn they want without the Covenant Eyes app to pester them. And leave all of us sweet, normal people alone. And let us raise their children.

Until that blessed day, or until I get smarter, I read and write and dream. It’s what we do.

Once more, with feeling, something we can all learn from:

“God is in the details.”

“Less is more.”

“Content dictates form.”

~ The three guiding principles of genius Stephen Sondheim

Love or something like it,

Miss O’