A letter of gratitude for my friend and writing teacher

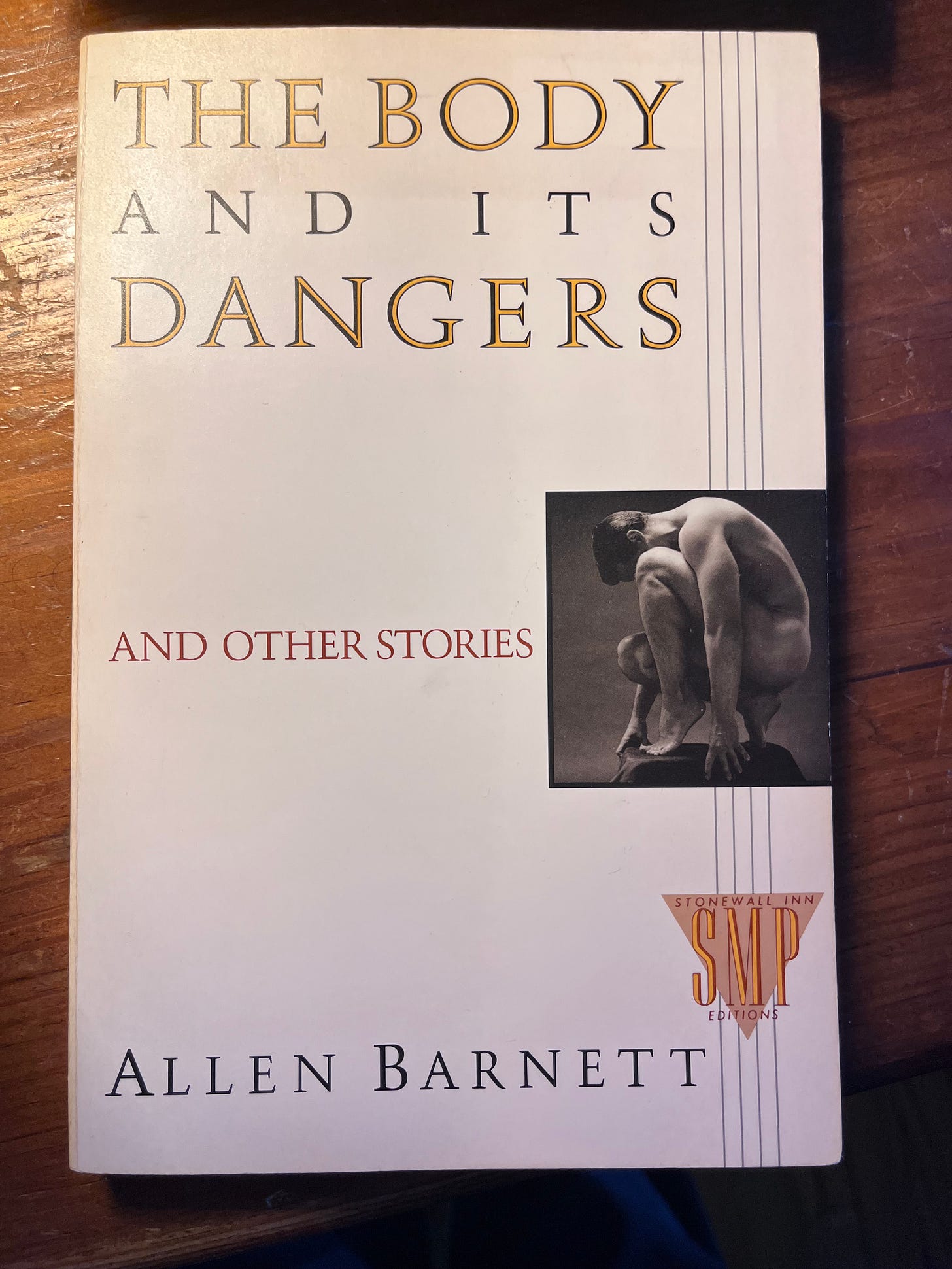

In July of 1991, writing professor David Huddle brought recently-published Allen Barnett to the campus of the Bread Loaf School of English, where I was a graduate student in my second summer. In 1990, Barnett’s debut collection of fiction, The Body and Its Dangers and Other Stories, was a critical smash; but a year later, Barnett was dying of complications from AIDS, a disease that features in his stories. David Huddle, a popular professor who taught the courses American Short Story and Fiction Writing, hosted an evening in the Burgess Meredith Theater on campus so that we all might hear Barnett read from his book.

The brown suit Allen Barnett wore, I remember, dwarfed his fragile body; as he took to the lectern, he said sincerely into the microphone, “I hope I don’t die while doing this.” He was not being histrionic; he would be dead in less than a month upon returning to New York City. I found the story he chose to read, “Snapshot,” devastating, and his reading was just beautiful. I still hear it in my mind. What struck me as much as Allen’s reading was the gravity, kindness, care, and sincere admiration that David showed in his introduction of Allen, his enthusiastically urging us to buy the book, and the way he showed Allen around the campus, that tender care at a time when AIDS freaked out many Americans.

The day following the reading, I found myself in Barn 5 (we literally had our classes in rooms annexed to a barn, and it was great), a basement area where there was a special seminar going on about literary theory, or something related. I’d sat in a desk in the back, the old-fashioned kind, ca. 1970, for the kids out there:

Professor Huddle and Mr. Barnett walked in, David guiding Allen’s elbow, and took desks right in front of mine. I leaned in, “Mr. Barnett, I want to tell you how much I loved your reading.” And David Huddle, a professor my grad school friend George had had for American Short Story in 1990, and now Jean had for Fiction Writing, whipped his head around and said, “Where did you get that accent?” A lifetime of living in Virginia even with parents from Iowa had given me some Southern.

“Yes,” Allen Barnett said, turning painfully, carefully to look at me, “where did you get your accent?”

“I’m from Virginia,” I explained.

David said, “I’m from Wythe County,” and I said I’d gone to Virginia Tech (also in Southwest Virginia), and taught in Appomattox. It was old home week. I know I said words, and heard some other words from Allen and David, but I was just astonished to be chatting with them, as if we all sort of knew each other.

That evening, I took up a yellow legal pad and I wrote a poem/letter to Allen Barnett, so clearly dying, to tell him what his story had meant to me, and even more than that, the fact that he took an interest in my accent of all things. Unwritten was, “and you are dying; how could you spend that kind of time on me?” I put the poem/letter in an envelope, with Allen’s name on it, and wrapped it in another note for David. “Mr. Huddle,” I wrote, explaining in some way or another that I wrote this letter to Mr. Barnett, and could he send it to him if he thought it was something to bother him with; and if not, just toss it.

The following Thursday evening was the weekly bonfire at Gilmore, a men’s dorm a half mile into the Green Mountains, one of the summer resort cabins that Joseph Battell willed to Middlebury back in 1920, causing the Battell-named “Bread Loaf Mountain” to become a century long (and counting) graduate English program for teachers as well as a famous Writer’s Conference. So on Thursdays, walking in the dark along the dirt road to Gilmore, you could hear the students and faculty gathering to pour a beer, sit outside, and stare into a fire (Vermont always has cool evenings) as a member of the faculty read a favorite story. It was sublime. That particular evening, still deeply sad about Allen’s fate, I sat by myself by the fire. Soon, David came over and knelt beside me. “I sent Allen your poem,” he said. I nodded. We held the space together for a few minutes, looking into the fire, and then David quietly got up and walked to greet others. I can’t remember if I learned from David when Allen died, two weeks later, but I don’t think I did.

But those few moments in a classroom and by the fire formed and sealed my mystical friendship with David Huddle forever. We never had long conversations, never spent long stretches of time together. One summer, he suggested that he, George, Jean, and I have pizza together, and thus began a tradition for us, once a summer for three or four summers, David would crank Steve Earle as he drove us into Middlebury down Rt 125 to Rt 7. I know he didn’t do that with anybody else, and we all knew not to tell anyone. It was our thing.

In the summer of ’93, my penultimate summer, I saw David at the annual summer cocktail party on the porch of Treman, a guest dorm with a kitchen that also served as an evening faculty hangout for The Eleven O’Clock Club, a legendary gathering of wits, to which I was never invited. The cocktail tradition was a rolling invitation list over the weeks, where one “dressed up,” and faculty and students could hobnob over alcohol. David, in his summer suit, walked over to me on the porch with his gin and tonic; I (a nondrinker at the time, I enjoyed a tonic water and lime, but who’s to know?) in my purple summer dress greeted him. He asked about my plans for my last summer. The rumor was John Fleming was coming up from Princeton one last time to teach Chaucer, and I needed that era of literature to graduate.

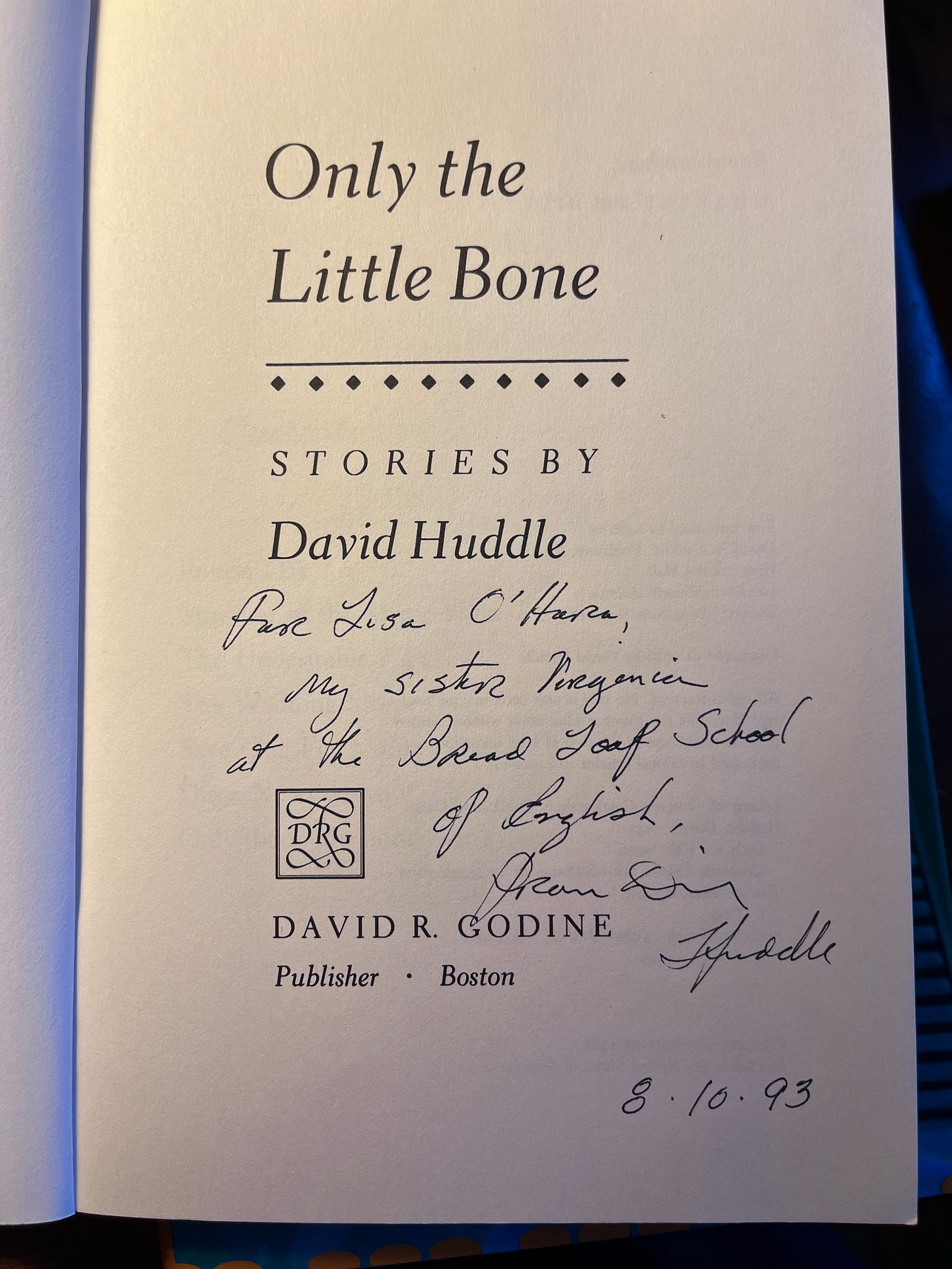

David asked, “Are you going to take my fiction workshop?” All these summers, it never even occurred to me to take a class with David. “Oh, no, David,” who always signed his most recent books for me, calling me “my sister Virginia” once. I explained that I wasn’t a writer but a drama director, George and Jean were the writers, that sort of thing. David looked tauntingly over his drink and said in his best kewpie doll voice, “Is the baby afwaid to take my workshop?” I glared at him. “Fuck you,” I said, “I’m taking your workshop.” He grinned. “Good,” he said, and sipped.

Bless that son of a bitch. Best decision I could have made. That last summer I took my two most challenging courses, challenging myself in ways I really hadn’t before, and David’s steady encouragement gave me the confidence to do it—that’s a longer story for another time.

My favorite greeting question of his, and I remember him once asking me this on his way to the tennis courts across from the library (not the best location), “How is your writing life?” David treated his students like fellow artists, and though I couldn’t be that, it helped me feel belonging.

David and I formally decided to have lunch together one day in the dining hall, and just as we’d sat down to talk, we were joined by another workshop student, a private school teacher (now the head of one of the most prestigious boys prep schools in the country) and a graduate of University of Virginia, like David. Tanned and dashing in his polo shirt, the fellow said, “May I join you?” and sat down without waiting for an answer. He immediately began schmoozing, complimenting David on a poetry reading he’d given with the likes of Donald Hall and others. David met my eye, which invisibly rolled, and I smiled; we shared this trap but it was David who was truly caught. My grin said, “You are on your own.” David’s gaze said, “I hate you.” Now that is love.

I believe that was the only time in four summers on the mountain that David Huddle and I ever tried to hang out, and it was not meant to be. David told George, Jean, and me that final summer, when they attended my graduation, that we would lose touch, as David said he never kept up with Bread Loafers. But he’d never reckoned with us. Over the years, I sent letters and cards to him, and he sent letters and poems in progress to me, to all three of us. Facebook later became the repository of greetings. George and Jean, who had married, remained in closer contact with David than I had, even visiting him in the hospital in Burlington as he was dying, complications of dementia. I knew something was wrong a few years ago when suddenly David left Facebook, where he had actively posted bird photos, shared poetry, including his own latest publications and readings, and boasted on his family. The onset must have been swift, is all I can say. Such a loss for his wife, daughters, and grandchildren, and a great loss too to his friends, readers, and fellow writers.

So I’m sharing this today because I finally found David’s obituary—he died in October; the obituary wasn’t published until November, and by then life happened and I didn’t search. George had let me know when he’d heard. I don’t know what made me think about David today, to decide I needed to write about him; coincidentally I got a brochure in the mail for the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference just as I started typing this. Something in the air, I guess.

David’s poems, short stories, and novels are still in print. He’s one of those so-called “minor writers,” which is sort of ridiculous because his work is wonderful, and you realize these tiers, these hierarchies, are silly. What is better than David’s “ABC” from Story of a Million Years? What’s more moving and beautiful than Allen Barnett’s “Snapshot”? There’s so much wonder to find in the world, so many encounters that teach us about ourselves, that moor us in the most turbulent of times, you have to know it all counts big, however small or quiet.

Hoping you find any consolation you need for yourself today, that you might take a moment to think about the teachers in your life. Bless them.

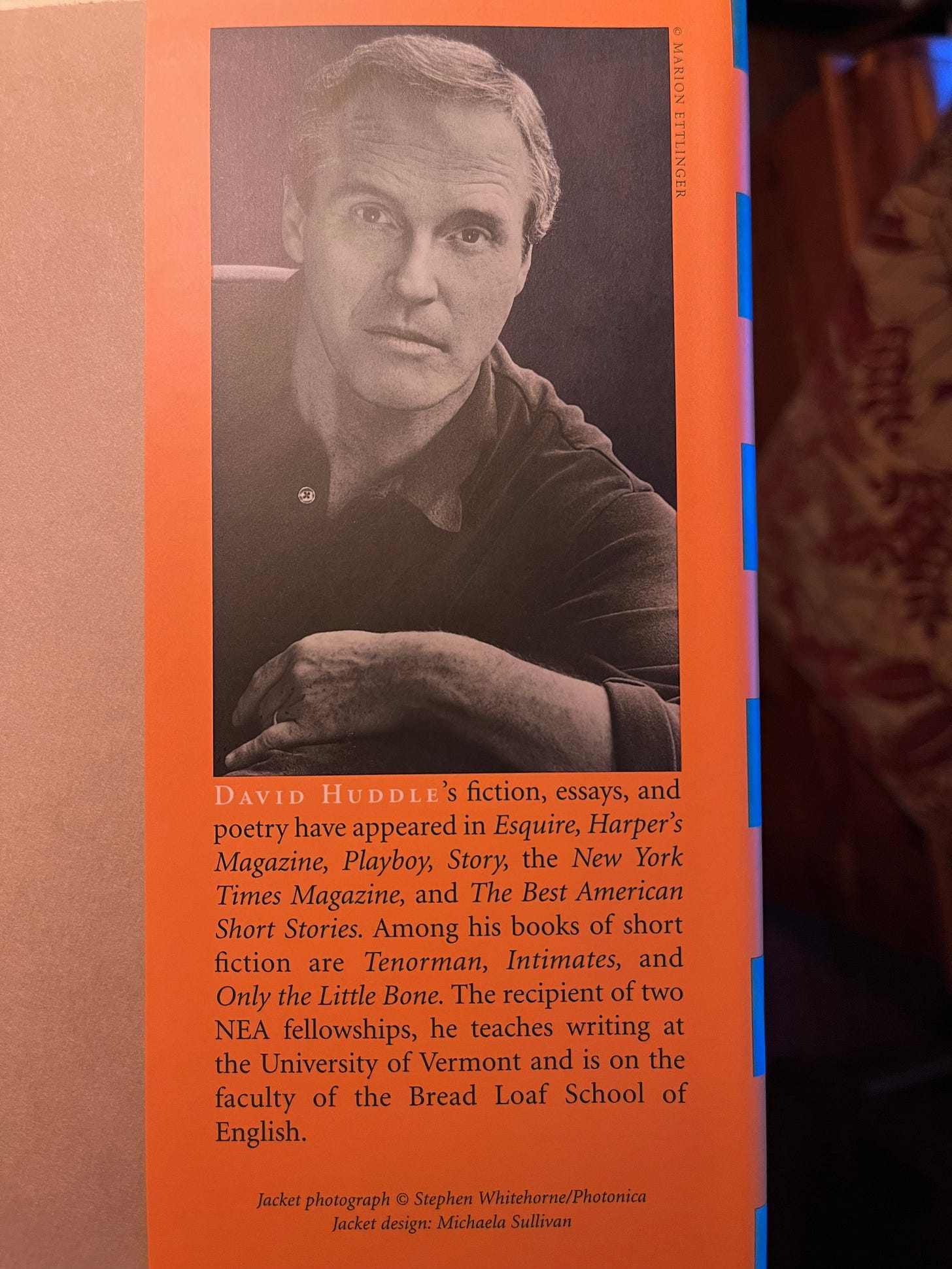

P.S. I loved to show friends this author photo. “Here’s why I took his workshop,” I’d say. David would have choked, catching my eye. I will always miss him.