Moments in my chaotic New York City week

So all the ick news first, aside from all the Musk-Trump criminal dismantling of every living institution in America so that it’s close to unrecognizable (taking over the Kennedy Center? The National Archives? closing what Department?), I learned at work this week that the two editors I supervise applied for a transfer to another (lately resurrected) department where they’d previously worked because they can do what they are best at there (I choose to believe it’s not about me) and got it, and that I will have to finish a huge project probably alone, the timing being what it is; then, at my ophthalmologist’s office for a checkup, I learned that not only am I at the beginning (and still reversible) stages of diabetic retinopathy, but also that I owe an outstanding balance of nearly $500 (of deductible-meeting crap) from visits over the past four years because their billing department never sent me the bills; and then I learned from my CPA that my company inexplicably failed to take out the correct amount of tax (and all week I’ve tried to correct it for this year, but the system doesn’t work, and we no longer have humans working in HR (take that in) and I am screaming into screens) and so instead of getting a refund, I in fact owe some $1,500; and the tendinitis in my write-hand (punny ha ha) wrist is so bad still after three months, medicines, and PT, that I would have to spring for a cortisone shot (sweet, sweet relief after the injection site pain and, obviously, the bill). Poor fucking me.

But one day this week—I think it was the eye appointment day, Wednesday, when I returned home with dilated eyes and shock at hemorrhaging money—on the way into the city, a Black female conductor announced at every stop (because the N-W-R-Q lines still do not have recorded voices to announce stops, and I love that) something to this effect: “Ladies and gentlemen, let the passengers off first, let’s help each other out, everybody, let the people off first before you try to get on. Move into the middle, people, help everyone out, we’re all together here.” Love her heart. On the way back to Queens that same day, a Black male conductor did much the same, adding on occasion, “It’s not about the price of groceries, everybody, just help each other out here and move all the way into the car.” This same conductor also used the intercom to explain the location of every staircase, connection, and elevator at every single stop. A total doll.

And if you are like me, you can’t help but look up and down the train car, men, women, children, every color and shape and gender and age and religion and background and profession, staring into phones, or not; bundled up, world weary, and it hits you all over again that the reason “white middle America” is afraid of brown and black shadows is because they literally have no idea how New York works. It’s not perfect, never that, but it works. Look at us. Us. Right here in this train car, crowded, or not, for miles of stops along our way. Not yelling at or killing each other. All of us just being.

Also in my travels, I found myself thinking about a poet friend who lives in a rural area, who years ago, when I mentioned how much I loved the movie Lost in Translation could only grunt in disgust. When I asked why, she said of the lead characters, “All they did was squander an opportunity to see Japan.” I had to think for a second, because I was remembering the filming of Bill Murray’s whisky commercial, the Tokyo karaoke bar, the hotel bar nights, Scarlett Johannson’s quiet excursion to a Japanese garden and learning flower arranging, and of course the hilarious trip to the ER so Bill Murray can get Scarlett’s broken toe seen to—all these relationships and stories they will have to tell about, or not, when they return home. What did my friend mean, “squandered”? I started thinking. I guess another view is they didn’t really do all that much…and then it hit me. I said, not at all angry, but with a sense of discovery, “You’ve never traveled outside the country, have you?” She looked at me suspiciously, and slowly shook her head, as if her response to a movie shouldn’t depend on having had the experience. More to the point, though, she had almost never, within or out of the country, traveled alone. And there it is.

What was lost in translation for her in watching Lost in Translation is the feeling of sudden paralysis brought on by the jetlag stupor you feel combined with being quickly overstimulated in a new place while on no sleep, while being both excited by the prospects and daunted by selecting the best thing to do right now. The one universal is a bed (never one you can check into before 3:00 PM) and a bar or cafe, and heading to either one can give you a chance to sort of recover your wits (if you know how to manage the currency), but when you are alone with no one to bounce ideas off of, being in a new city, whatever the language, can be pretty isolating. One time, visiting London, I spent nearly one entire first day just sitting alone on a bench in Tavistock Square, where Virginia and Leonard Woolf had lived (in a no longer existing building, bombed out in WWII), underdressed (a cold day for summer) and disoriented, and in those days, a teetotaler. I could barely make myself try to find a place to have tea. If I did eat or have tea, I don’t remember. I remember a white-gray sky, damp chill air, and just watching people against green trees and grass and gray buildings.

Did I squander my first day in London? Not at all. Oddly, that first day of “doing nothing” is still the one I remember most vividly and fondly, whatever the discomfort and confusion. I was there, in the heart of London, on my own, unremarkable, on an ordinary day. Not bad.

As a result of my many NYC train treks this week, it also dawned on me that perhaps the reason I needed to leave Facebook, finally, was that my life in New York can be one of overstimulation even on the dullest days, and that Facebook had become more overstimulation, not sure which way to look, who I’m forgetting to check in on, that sort of thing. Maybe I’m just not wired for all that anymore. I know that many people can simply sit on a virtual Facebook bench and do nothing, or idly and dispassionately watch the goings on, not unlike I did in Tavistock Square or Scarlett and Bill did in Tokyo. You do you, as the kids say. However we engage, or don’t, we are all in it together, so move to the middle of car and let everybody onto the train. And remember to give people their space (remarkably, New Yorkers do know how to give you yours, even by a fraction of an inch, and if only the whole country could cotton on, that would be great). After all, everyone here with you is simultaneously present in a pubic place and also living a very private drama of their own.

All of this is just to say, dear friend, given all that you are going through in your personal life and against whatever landscape this letter finds you, I know that you may merely glance at or dip into this post, and I completely understand. Thanks for reading at all, and whatever you do, don’t strain yourself. Enjoy your Sunday. Let me hear from you when you get a chance.

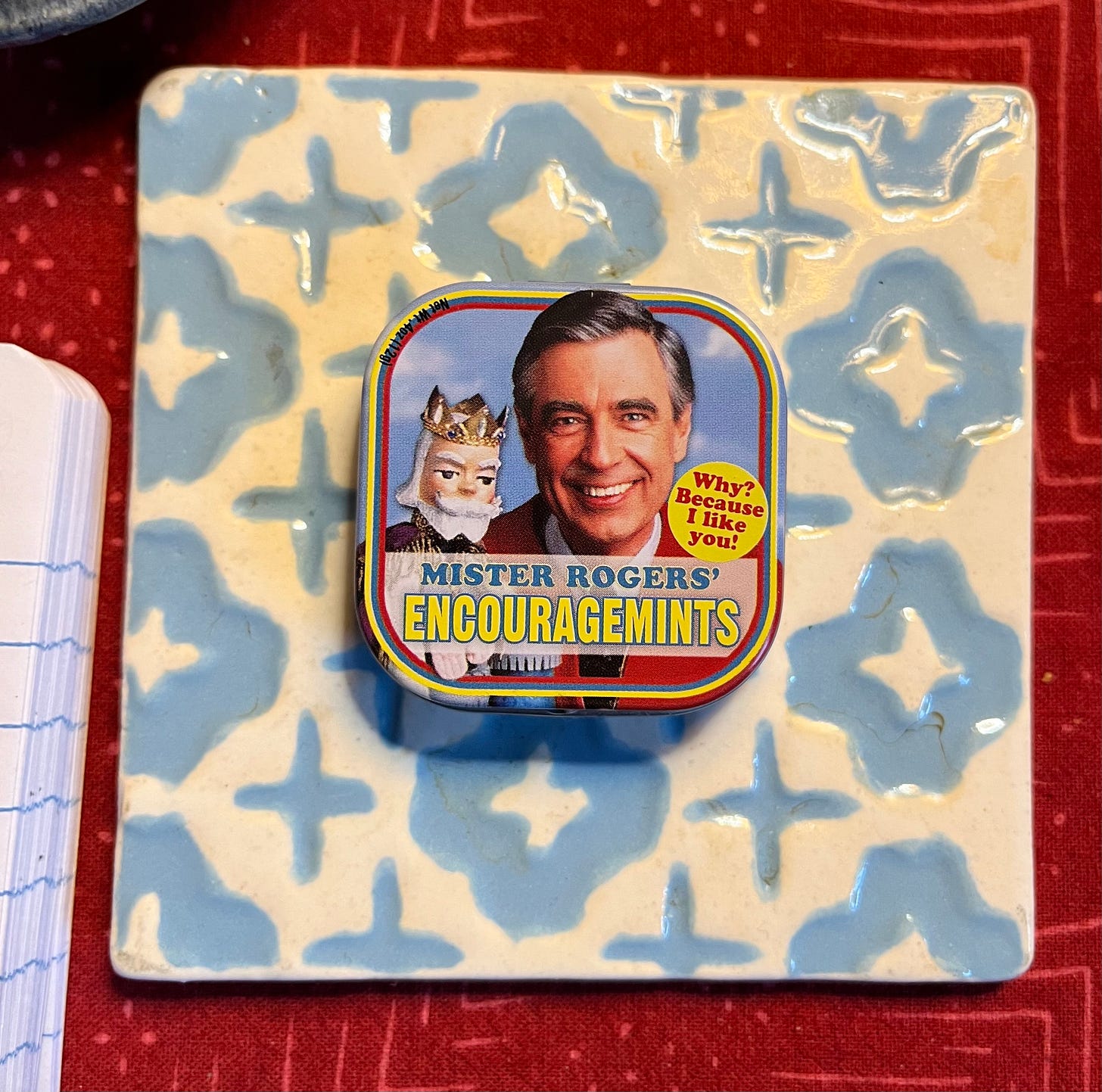

It’s been a long three weeks. Encouragement!

Love,

Miss O’

P.S. A few weeks ago I published part of a play I’ve been working on, but I don’t know if WordPress is the best outlet for me. Thanks to all who read it, in any case!