A few reflections on my mom, Lynne

Lynne died almost two months ago, on June 5. The other day I had an email from my friend Anna, who told me she thinks of my mom when she’s looking for something crunchy to go with her meal. When Lynne packed a little lunch for me to take on the train, a gesture she stopped doing in the five or six years before she died (not through lack of love but lack of energy), she’d ask, “What would you like for crunch?” (It usually came down to carrots or Cheez-Its or chips.) My mom was a strikingly picky eater, something I didn’t think much about, but noticed more than I was consciously aware of. In her last couple of years, down to 80 pounds and not out of bed too often, I’d see my dad, Bernie, running up and down the stairs from the bedroom, reheating her plates of small meals in the microwave—if the temperature was too cold, she’d stop eating, and desperate for his wife to eat, Bernie would warm it up. My brother Jeff is the same way—the food has to be the right temperature or he doesn’t want it.

By contrast, Bernie eats his spinach right of the can he just opened; I eat leftover Chinese chicken and broccoli out of the container from the fridge. Hot, cold, lukewarm (sidebar: I just realized I have no idea where lukewarm came from, so you’re welcome), it’s food. That said, both my dad and I have to have our coffee steaming hot or we don’t want it.

But one thing we O’s all agree on is that each meal should have a contrast of textures—something with a good chew, something soft, something with crunch. A little salt, a little sweet. I imagine that any human would agree on that—it’s something that makes grilled chicken nachos (topped with melted cheese, black beans, guacamole, salsa, and sour cream) a perfect dish (and luckily I enjoy them even as they get a bit soggy and cool over a long visit with friends).

And really, in a world of so few universals, you’d think we could agree that one of life’s great pleasures and purposes is to have the food we love, the way we want it, when we need it. After clean air and fresh water, and right before safe shelter, fine nourishing food of appropriate temperature and texture and taste is right up there. I find it sickening that anyone could deliberately starve any creature. I can’t stop thinking about this, and Lynne would feel it, too.

For whatever pleasures or pickinesses Lynne experienced in eating or not eating, she saw as one of her prime duties the feeding of her young. “So you have a ham sandwich on whole wheat and a Clementine,” she’d say, putting the Glad bag and napkin into the paper sack. “What do you want for crunch?”

I love that this stuck with Anna. Lynne seems to stay with people, and mostly through my stories. I’m glad I tell stories.

My friend Colleen sent me a card a few weeks back, offering condolences for the death of my mom, and remarked in the card that when I talked of her and told stories, I spoke of her as “Lynne,” never as “Mom” or “my mother,” and Colleen wondered why that was. Talking to my dad recently, I relayed this observation and said, “I always saw Mom as a person first, and my mother only incidentally.” He thought that made sense. I see Bernie the same way, a person first. They both made it clear from the beginning of all their kids’ lives that their marriage came first. “You kids can go to hell,” my dad said more than once during various moments of his children’s sometimes troubled adolescences, “all I need is your mother.” And it was true.

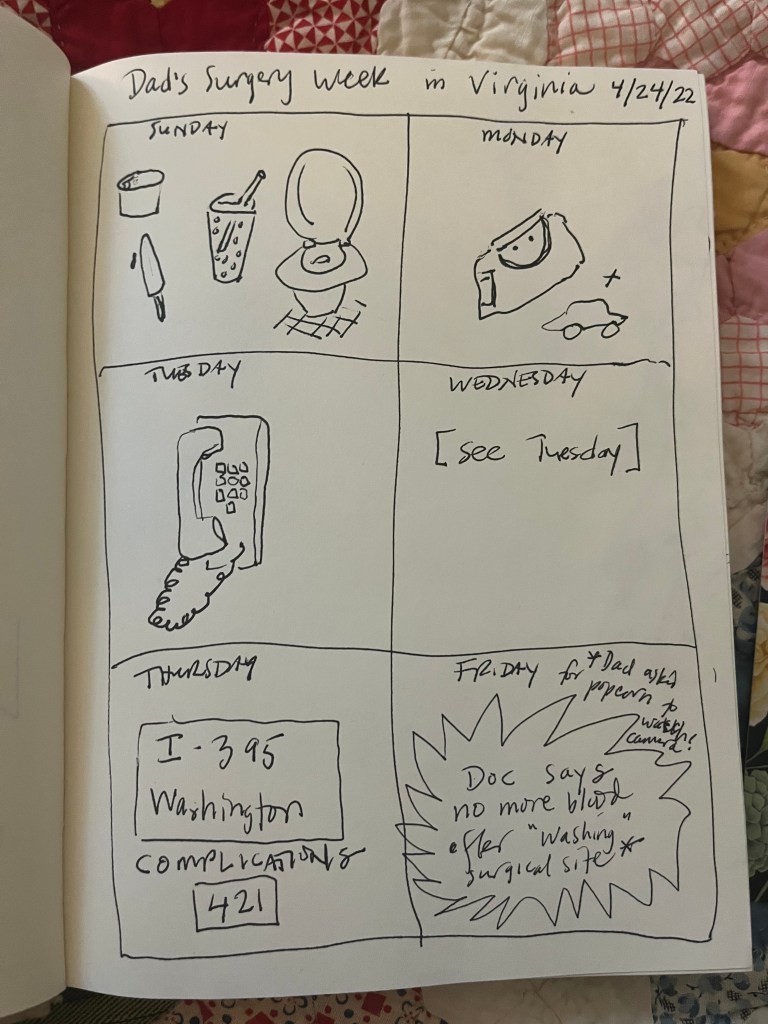

Back in 2022, my dad had surgery for the first time at age 88 to remove a mass (non-cancerous as it turned out) in his colon. This would turn out to the be the last year that Lynne was really mobile, and even then it was limited. Here’s from my sketchbook of that time:

I told you this I’m sure, but before I took the train down to Virginia from New York the week of the surgery, Lynne asked, “Why are you coming?” My brother Jeff lives with them, but he works a labor job, and as an editor I can work from anywhere. She still didn’t see the point. I knew that after a major operation that there was no way Bernie could lift, open, or otherwise help with anything, and that my mom was too weak to turn doorknobs. (I’m not kidding: years ago my father (who is a neat freak, so this was hard for him, I know) started leaving all the closet doors ajar, and even made the toilet paper hang long so it would be easy for his wife to reach; it wasn’t until after Lynne died that I realized why all that was.) And if you are waiting for your parents to realize they need you, that is not happening. So you go. A few days after my arrival, Lynne looked at me hard and said, “How did you know?”

During his recovery, in Bernie’s unstoppable neat freak rush (he is famous in the family for breaking and chipping every plate, glass, cup, mug, ornament, you name it, that he touches), he broke a precious object. Poor Lynne had a vase she was really fond of, at least 50 years old, and one morning I came downstairs to hear Lynne yelling, “How on earth did you break that?” And Bernie is yelling, “Well I had to pull the shade down,” and she’s yelling, “Why? There are curtains there, and I really loved that little vase.” It had been nearly 60 years of suffering the sloppiness, and yet all the love, you know?

So I went online, and I searched. And it took some time, but I found it. The exact same vase. I gave it to them for their 59th wedding anniversary. Neither of them even noticed its return. Ha, ha.

Bernie and Lynne. I knew people growing up—good buddies and neighbors—who would say that their mom or their dad was their “best friend.” I found that creepy. Once when I was in middle school, or maybe early high school, Lynne said to me out of the blue, “You don’t care that we aren’t friends, do you?” I didn’t hesitate in saying, “No,” because Lynne raised her kids to be independent creatures, even as she fed and bathed us and took us to the dentist twice a year. It worked for the O’s.

At a reunion of my dad’s side of the family out in Iowa and Nebraska nearly 30 years ago, my youngest brother Mike told a girl cousin (one of 37 living) that we weren’t really raised with hugs. She asked, “How do you raise kids without hugs and kisses?” When we got to our Uncle Al’s farm, five of her six children walking toward our cousin’s Aunt Lynne, who walked purposefully to greet us with a wave and a back pat, Mike said, “We don’t hug, do we Lynne,” and our mom declared in perfect time, “No we don’t.” Our cousin gaped.

Hugs and kisses are nice, but some of the most screwed up people I’ve known in my life had all of that and a mom or dad for a best friend. You know. Every family is different, the needs are different, no one does it perfectly. The hot and cold, the bitter and sweet, the soft and the crunchy—I’m grateful for the textures Lynne brought to our lives, for the nourishment she gave, for the smarts she had. We may not have been smothered in kisses, but because of her, the O’Hara kids know injustice when we see it, and we are not afraid to call it out.

Crunch.

Sending love,

Miss O’