You Are Here

You don’t know where they keep, say, the batteries, the dust rag, sure, but really it’s about the morning and evening meds for both of them, your dad and your mom, both 89; and about the bills they pay online and by check, and online are they automated or not? (Only the credit card isn’t, but the trash bill has to be paid by check, and while you found the updated auto insurance policy you can’t find the bill, and right now your mom can’t remember how she pays it and your dad has never written a check in his life, since he has mom for that). Last year when you and your brother Jeff had to get them a new computer, and it was a large laptop, for some reason your mom could not seem to understand that the keyboard on the laptop does exactly the same things as the freestanding keyboard did, the screen is a screen, and the mouse is the same mouse, whereas your dad, who had avoided all things computer except to check emails, sort of, while standing by your mom, is now the email guy, if barely, but he doesn’t know anything about the bills. You see the desk, piled with clusters of old envelopes of bills in blue rubber bands, just as the downstair buffet is, and the console behind your mom’s chair, all labeled in your mom’s neat, fine point, all-caps script, some with notes like “KEEP,” but that doesn’t tell you why they are being kept, and your dad as no idea.

You then can’t help but notice that the kitchen and bathrooms could do with a cleaning and subbing in of fresh towels. In the linen closet in the small upstairs bathroom is a helter-skelter collection of sheets, pillow cases, and towels of all sizes, in some shade of blue or pink, most all of them frayed from 30+ years of use, and at the bottom of the closet are baskets of cleaning products and small appliances and tools and boxed tissues and rolls of toilet paper, none of which you can use for cleaning the sink the way you want to, since there’s no rag or sponge, because of course there isn’t. “It’s hanging on the towel rack in the downstairs bathroom,” your dad says, because when your dad cleans the bathrooms (your mom hasn’t been able to scrub or get down on the floor for a decade), he does them at the same time, see, so the rag ends up downstairs because he starts upstairs, see?

So then the meds. Dear god the meds. The morning ones for your dad are downstairs in the kitchen hutch, in a lidless round tin that once held Danish cookies, whereas his evening ones are loose bottles resting on his low dresser by the mirror; and all of your mom’s, the morning and the evening, are in the old Easter basket, atop the tall dresser by the TV, labels so smeared by your dad’s hand oils (within a week or so) that you have to strain to read them, even under and lamp and with your low Rx reading glasses. You ask, “What are these for?” and your dad says, “I don’t even know anymore,” so you study them, make lists. With a Sharpie fine-tip you find in the console behind your mom’s chair downstairs, you label “A.M.” and “P.M.” on each bottle, separating the bottles (and they aren’t really “bottles”?) by parent. On Amazon you order AM and PM weekly meds sorters, and when they arrive you take a Sharpie and write on each side of one, “LYNNE” and on each side of the other “BERNIE” (and on the one you got for yourself “LISA” which is weird because you, Reader, have some other name, probably, as do your parents, for that matter). You will need to sit with your dad to organize them. Note: Without the muscle memory of opening plastic bottles and walking from upstairs to down at the same time every morning, and downstairs to up at the same time every evening, your dad will spend weeks figuring out the new system, and he will take his evening meds in the morning and to forget to give your mom her meds at all; you realize you have to check on this and coach him. And when he does finally get the hang of it, his OCD kicks in and he refills WED AM as soon as he’s taken it, so you can’t tell if has actually taken them or not, and it takes three tries to get him to see what you mean. Now you realize you will have to check and actually ask him every morning and every evening if he and your mom actually took their life-saving medicines. Check.

Backstory, or Why I’m Doing This

The routine, see, is all new, because your 89-year-old mom tripped on a bathroom rug (the rugs the doctor told you to get rid of years ago but they are so pretty, and small, and what could go wrong?) in one of the world’s tiniest full bathrooms (second only to yours in New York City) in the middle of the night, fell, and cracked her hip. The EMTs had to get her down the stairs of a split foyer using a wheelchair. Almost 24 hours and a few tests later, your mom is transported from the local hospital to a more advanced medical center, where neither your brother Jeff (who lives in) nor your dad visit her for three days because each morning they’d call, her ladyship would declare, “Don’t drive over here! They are transferring me to rehab today,” so they didn’t, even after the second day when she called again at noon and said, “Haven’t you left yet?” because men. And when you finally arrive on Amtrak via subway from New York City (taking two days to put up the storm door, take down the AC unit, clear out the fridge, arrange for your wonderful upstairs neighbor to get the mail, water your plants, flush the toilet, and run the faucets once a week, and pack your work and home laptops and chargers and meds and a few changes of clothes) on the fourth morning of her hospital visit, you all drive over and you track down her nurse and you explain, “I’m her daughter from New York, my father and brother actually listened to her, because she runs the show, and we need to understand what is happening, and I’m so sorry,” and you explain this because you realize the nurse and doctor have assumed she has no one who cares about her, and of course they assume that and this is so, so not the case. And everyone feels terrible. Your mom really doesn’t seem to know what is going on.

First things first, you replace her matted gray wig with a combed-out silver wig, and your mom instantly feels a little better. The nurse has told you how your mom put on lipstick every day because “my husband will be here soon,” and after two days, they thought she had a negligent husband. You toss her matted wig in her “go bag,” a bag that each parent has and has needed more than once over the past few years.

You meet with the doc, figure out next steps—the fracture is inside the bone so there’s no operating they can do, it just has to heal on its own, but your mom only weighs 88 lbs. and wasn’t in great physical shape in terms of muscle mass to begin with, but at a rehab facility you know they are only going to work with her for 15 minutes once or twice a day, and you can do that at home, and be with her. Now your role gets really interesting.

You spend your first days home fielding calls from equipment suppliers and a managing nurse and the home care company to arrange all the caregiving. You have to help your dad, who will be 90 in October (and you had to take him to the ER last Christmas because he had a TIA, or ministroke, right in front of you, you running upstairs first to tell your mom, who is napping, which she has to do a lot these days, where you are going; and then spend the day in the ER with him, finally having to call your sweet brother to take over when he gets home from work because your head is so sick from not eating all day you need three ibuprofen), figure out how to get her to the bathroom on her walker and onto the raised toilet seat; and then your wonderful half-sister who worked in a retirement community until she herself retired, tells you to order a commode to keep by her bed, which you do, and it comes the very next day thanks to Medicare and their managed health care (the result of benefits your dad had from his 42-year union job, and thank the gods of unions, and why don’t we all have this level of care?) and is a godsend.

Oh, and the first thing you all did, by the way, before your mom got home via ambulance transport, was to figure out how to get her onto the main floor of the house, which is a sort of half basement with five steps down (note: never buy a split foyer), bolstering the foldout couch in the playroom addition with cot mattresses (after first trying to arrange cots and an air mattress in the little living room, which is closer to the bathroom), and removing all obstacles that you can, finding the sheets, figuring out blankets and pillows and all that. Will this work?

Pardon the Lack of Narrative Cohesion

And if all this information isn’t chronological it’s because it’s a jumble in your mind and a jumble in routine almost immediately and consistently, and that’s because you must spend all the time you can in the dining room on your work computer having Zoom meetings and trying to work on this new project for your income to keeping coming, while also remembering to take walks (you’ve done three in three weeks) when you can because of your ever increasing stenosis, but you don’t dare leave your dad alone with your mom because he has this tendency to go into the kitchen to cook, say, or want to go to the store or run another errand, convincing himself that your mom will be fine for 10 or 20 minutes (I mean, she’d be alone in the hospital room, he says, and you say, monitored), but his 20 minutes usually stretches to 45), so you have to run into the other room to be with her when he leaves (she always needs something, like water, which you have to remind her to drink constantly (and she’ll only do it if you put in a straw), and that’s just what life in an invalid state is), so you handle it, and then help him with the groceries when he gets home, and pause to pick up your mom’s water cup again and push it over toward her with the straw as you say, “Have some water,” while she screws up her lips and sighs; you have learned by now that to get your mom to do anything, you have to suggest it, count to ten, and watch your suggestion become her idea before she does it, and you are once again beyond grateful for your theater training to carefully observe without judgment, as if you were your mom. Now drink this Ensure. Sigh. Mom, you point out, you are down to 83 pounds. She drinks.

Yesterday your mom’s doctor called, and you put her on speaker; since you can’t get your mom to get up and exercise so she is strong enough to get to and into the car, her doc puts in an order for a wheelchair, which is fully covered by Medicare (which you learn when the supplier calls later, but there’s this rental contract coming online that you have to sign, and if the link is expired you can call this 800 number and someone will assist you, and your brother says, “Thank god you know how to talk to people because I could never do that,” and it’s just what people have to do sometimes, another reason everyone should take an acting class or be a teacher for a minute).

Your mom’s doctor, by the way, says the key thing, the main thing, and it’s not about wheelchairs: You can fight like hell and do the exercises and work to get better, or you can stay in bed and not get up. Both are reasonable options. They are. And the next day your mom seems determined to try all the exercises with the OT and the PT, and then the day after that she stays in bed, slack jawed with eyes closed, and barely eats. And the day after that is a blend. But your dad, with all the love in the world and more energy than most men of 60, cleans out her commode and walks behind her on her walker on her way through the laundry room to the bathroom, when she’s up for it, and all you can hope is that he doesn’t get another hernia or have a stroke. And, in the words of the great Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., so it goes.

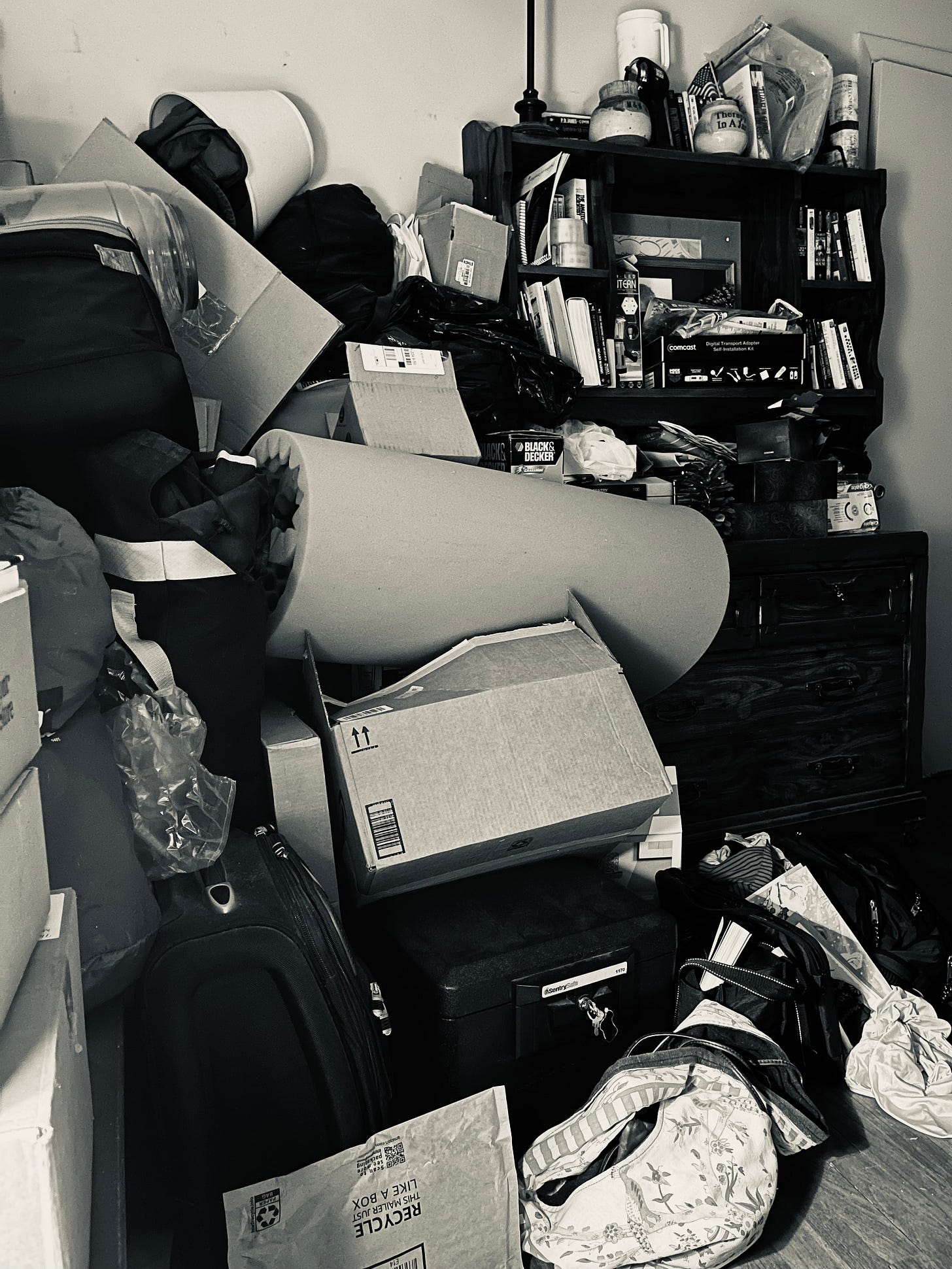

And in the meantime, you sleep in a room that was once your first bedroom which is now a dusty junk storage room with a bed in the corner, the bedpost serving as a closet and the front edge of an old book- and medicine- and tissue box- cluttered dresser for your toiletries, collecting your dirty clothes on the floor next to your backpack and purse. And you can’t help thinking, in passing, that this could be your life for years, your apartment in New York a distant memory, possibly a place you never again inhabit even as you pay your bills. But you can’t live thinking like that. Moment to moment, day to day. You can fight like hell and do the exercises and work to get better, or you can stay in bed and not get up. Both are reasonable options. But not, not now, for you; you have one option only because people are depending on you. And it could be so, so much worse. And it will be. Just a matter of time.

(Note: In this crazy world, it would have been easy just to come down here and not tell anyone besides your immediate neighbors in New York, not your friends, not the people at your job; you could literally live anywhere and under any circumstances with no one the wiser. But if you feel you have to hide and protect your friends from the complexities of your life, I hate to break this to you, but you don’t have friends. There are times when we all feel friendless, so ask yourself, “Have I shared my life?” and if the answer is no, you risk losing all connection, so for the love of god, share, and for the love of god ask them about their lives, and want to know.)

Love and kisses, with all the gratitude in the world to friends who text.

Miss O’

These are difficult days, but precious. Your heart is already so wide, Lisa. The place in time you’re now living in with the challenges your parents are facing will open your heart to further depths. It’s in the times like what you’re experiencing now that we can grow to experience further what it is to be human inhabiting a body, what it means to love ourselves fully into wholeness even as we fall apart. You are holding presence with your parents and that is a great gift. The transformation your parents are experiencing will transform you too. We’re taught in our culture to take charge of situations, but it’s not easy to know how to respond to challenges that can’t be fully resolved, or to circumstances we find ourselves in when we know things aren’t necessarily going to get easier. But love is present, and you are sharing life. That’s what we’re here for.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anna, thank you so much for your wisdom. One of my brothers called yesterday to tell me how grateful he is to know I’m here, that he can breathe because of it. And I didn’t know how to tell him, I’m not doing it for you or your comfort; I’m doing this because it’s a privilege, however frustrating or confounding or challenging, and despite the inevitability of the outcome. Anna, you have expressed what I didn’t even know I meant. Love, love.

LikeLike