Reflections on art and life in the age of American Surveillance

Today, in the wake of all the grave threats facing anyone opposed to the Trump administration—citizen or noncitizen, federal worker or civilian, famous or ordinary, —even normal people just traveling, like the just-released woman from British Columbia traveling to the US from Mexico detained in a cement cell with thirty women, fed on cold rice for the past two weeks, no regular access to a toilet, with no due process (one woman in her cell has been there for 10 months with no hope of leaving, no one to help her); or like the British tourist who was arrested while backpacking in Seattle, detained and still not charged (both women white, English-speaking, without criminal records)—in the wake of all this, as I say, a friend of mine asked me if I was going to continue to write my letters on Substack and WordPress.

Yes.

As Trump invokes the Enemy Aliens Act and carries out the wet dream of White Christian Nationalists that is Project 2025, no one is safe. Do or do not, be important or not, be famous or not, be humble or not, be a child or an adult, a Democrat or a Republican, pardoned or not, Trump friend or foe, literally no one is safe from all this. (Did you see Sophie’s Choice? How many times do you have to read the fucking “First They Came” poem?) The sadistic joys of kidnapping, detention, torture, and, no doubt, eventual killing are endorsed by fully 37% of American citizens. They are willing participants and apparently glorying in the promise of the end of the democratic republic. They whine when they are personally affected, sure, but as one Nebraska rancher I heard on Instagram said—and she is losing everything and voted for Trump—she’d do it all again. You cannot fix this level of stupid, you cannot fix sadists. All you can do is outnumber them, out kind them, out organize them. Outlove them. And die trying.

It’s the absurdity of it all I cannot fathom. In a recent episode of this season’s Finding Your Roots, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., reveals to actress Debra Messing the truth about the fate of her Jewish-Polish ancestors in Krakow. One such relative, a pattern cutter in a garment shop, was among those killed in the Holocaust. In a moment of what scholar and philosopher Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil,” conscripted Nazi soldiers carried out orders and exterminated simple working people in Poland and elsewhere, people they didn’t know, for no particular reason other than they were told to. Ordinary working people.

A pattern cutter. In a little garment shop. In Krakow. And his wife, and his sister. Messing had no idea.

Tom Stoppard, in his Broadway play Leopoldstadt explored his own discovery of Eastern European uncles and aunts and cousins who were murdered in the Holocaust. The play, which I was lucky enough to see—it was stunning—was performed over two and half hours without intermission. Why no break? Because the audience would have walked out, baffled by banality, after Act I. The family, ca. late 1800s, was so…ordinary. Middle class, an affair maybe, a little business trouble; a simple holiday blending Christian and Jewish traditions, having dinner. That was the whole point. When the play shifts to 1955 in Act II, they are all dead. A relative is reckoning with this horror and the audience is, too.

It’s just insane.

No one could have been less important than a Romanian boy of 15, Elie Wiesel, and his family, as described in the memoir Night. The inhumanity and terror of the Holocaust has been so well-documented by survivors like Wiesel and others, like Primo Levi, that you cannot honestly believe we are reliving those exact times. And in the United States of America, too many of whose citizens died fighting Nazis, it’s unthinkable.

Yet here we are.

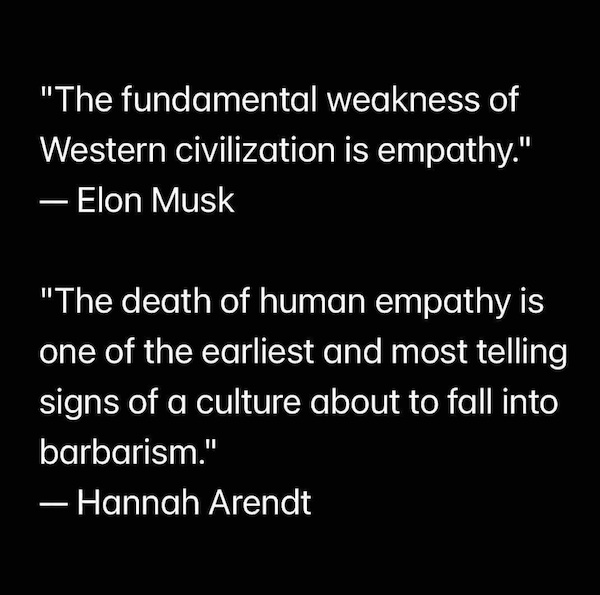

At 59E59 Theater in Manhattan before the election, I saw Mrs. Stern Wanders the Prussian State Library. (The promo material gives away the play’s surprise, that Mrs. Stern is Hannah Arendt, which is I guess because they didn’t trust the audience to know who she was.) The play gave me all the awful prescience that we were about to face the same interrogations Arendt endured; yet by gaining the empathy (there’s that evil word for which Elon Musk and his army of Christian white supremacists will have us all murdered) of her Nazi interrogator, Arendt was aided in an escape over the border. She famously went on to report on the Nuremberg Trials and warn us about how regimes like Trump’s form. Her books should have been text books in American high schools.

Last summer (I wrote about this somewhere already), I was lucky enough to see the play Here There Are Blueberries, a true story, wherein researchers at the National Holocaust Museum found themselves gifted, quite problematically, with a photo album of Nazi officers and their secretaries having the time of their lives at Auschwitz. Not an inmate in sight. The photo in the promo material is of a group eating blueberries, in a spot that was not far from the ever-burning crematorium, all smiles, not a conscience among them.

A few years back, I saw the final preview of a Taylor Mac comedy, Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus, in which a Roman slave, played by Nathan Lane, begs his two fellow slaves to stop preparing all the dead for burial. Let them rot—how else will all these Romans quit having wars? If we keep doing the dirty work, if we don’t unionize and end this complicity, how will it ever stop?

The two women keep embalming. (I think our audience was the first one to get it, and maybe the first night the play fully came together, because you could see the cast was stunned at our screaming standing ovation; the critics panned it, having seen the play before it was ready to be seen. And wow is it timely now.)

I think also of a fabulous Broadway revival of a play in verse called La Bête, in which Mark Rylance played a charming, verbose rube who talks the king in a 17th century court into making him the new court playwright, and David Hyde Pierce played the snobbish playwright who is unseated. In the final moments of this hilarious and frenetic farce, the audience realizes that in fact Pierce’s character is right, and Rylance’s character is in fact a deceptive, cunning, dangerous beast who will bring down the order with his appointment.

And my god, here we are.

It’s through the theater that I process life, even prepare for life. The way some people look to scripture I look to playwrights, to the artists always, as guides on what was, what may be, what to do, how to behave, what to dare in our increasingly dark times, surrounded by confusion and cowards, facing unending threats and evils everywhere we look.

And these monsters are just getting started.

UNLESS. Unless. Unless. Unless.

It’s a big ask. But we can’t give up.

Love,

Miss O’