Telling truths on Presidents Day

“I cannot tell a lie.”

~ George Washington, First American President

Ironically, this famous quote is itself a lie (how American), but more on that later.

The magazine Vanity Fair (to which I no longer subscribe) includes, as the last page of each issue, The Proust Questionnaire, a set of questions originally asked and answered by novelist Marcel Proust and now used to learn more about the globe’s favorite obsession, celebrities. The questionnaire has some interesting questions, and some shallow ones, but the answers can be revealing. I’m often struck, for example, by the way powerful men, even decent ones like George Clooney, answer #12: What is the quality you most like in a man? “Loyalty.” As a woman I read this as, Truth telling is a deal breaker. As for #13, What is the quality you most like in woman? men generally respond, “Patience” or some other subservient thing. It’s interesting, if limited.

Interesting, If Limited could be the title of my memoir.

Walking around the neighborhood, I found myself thinking of Question #9, which is, On what occasion do you lie? Often the celebrity of the month who has chosen this particular question among the many, will respond, “To spare someone’s feelings.” Fair enough.

But speaking as a fairly honest person who has lied on numerous occasions while also valuing truth, I wondered if any of the situations in which I lied had something in common. I’d like to say something pithy, see, when it’s time for my Vanity Fair moment, so let me note just a few examples, categorize them, and see if I can find the common ground.

1. Once in second grade, Mrs. Angle—I’ve told you this story—asked us after nap time with our heads down on our desks if anyone had a dream they’d like to share. I raised my little hand and got up in front of the class and, making it all up (obviously) to entertain my friends, described how we all went to Egypt to see the tomb of Tutankhamen. I pointed, “Juanita was there,” and again, “Ingrid was there,” and Mrs. Angle snapped, “You’re lying. Sit down.”

2. On a high school field trip during my sophomore year, to take the singers and pit orchestra to a neighboring high school to perform scenes from South Pacific as a promotion for our production, our sponsors, Mrs. Combs and Mr. Carnohan, realized they’d forgotten to send home permission slips with us kids. Only when the bus driver asked if they had them did they realize. I stepped up quickly, “Give me ten minutes.” I had everyone write out a permission slip on paper we all collected from someone’s notebook, and I signed each slip in chameleon-like handwriting. Mrs. Combs looked stunned, but she took my pile and off we went.

3. When I’m late for something, like work, I have blamed the subway (and have been caught out by a colleague and supervisor on the same line) because I’d rather not say, “I have IBS and had to run back home halfway to the stop because I needed to shit again.” (Finally, I just told the truth. No one asked after that.)

4. I once helped make a company-wide Answer Key set, compiled for the whole floor of my 2 Penn Plaza office, when this one president took over and, to prove his power, spent easily $100K to create something like 30 separate “learning modules” complete with “tests” on corporate “life” and business, modules that included short films, voice overs, and reading material on slide presentations, and if you didn’t get all the answers correct on each test, you had to start over, the whole module. We had massive publishing deadlines at the time, our nerves hanging by a thread. To what end are we doing this? But your job was on the line. A few of us—no doubt my idea—began printing out all our 100% test answer sheets which we labeled by module, punched holes, and stuck them in an unmarked three-ring binder. and set it on a file cabinet in our pod We didn’t even hide it. Eventually even our supervisors, to say nothing of executives and vice presidents, began ambling and ultimately marching over our pod to get the book, because 1) these tests were useless to our work; 2) the president was doing it to be a dick; 3) he would be out on his ass soon enough (they always are) once he was eligible for that golden parachute—we endured a period of a few years in which a succession of dicks who were pushed out of one company division and over to ours until they could retire. It was not fun. And yet, our important work—work that corporate didn’t in the least understand—somehow went on, great as usual. Hmmm. Who’s the parasite, Elon? (And how do I really feel?)

5. When the famous Westway Diner on 9th Avenue was taken over by new management maybe six or eight years ago—all the old-school career waiters replaced, the desk staff and chefs gone, the classic booths and tiles plowed under for white and gray blah—I happened in to check it out, and in addition to the place being bereft of atmosphere, the food sucked. “How did you like it?” the aggressive manager asked me about inedible spinach pie, which was a block of bone dry phyllo with almost no filling. “Mmmm,” I said, not wanting the poor new chef to get canned. Let someone else tell them; consider this a funeral donation. (It’s since recovered.)

What do all these occasions have in common? Well, they are lies of convenience, I guess, trying to smooth something over, or using deceit to help out friends or struggling folks; on reflection, I tell few lies just to save my ass. That’s how I was brought up. But I’m not stupid enough to believe that always being honest is smart. As my friend’s Montenegrin immigrant father used to say, “Honest and stupid are two brothers.”

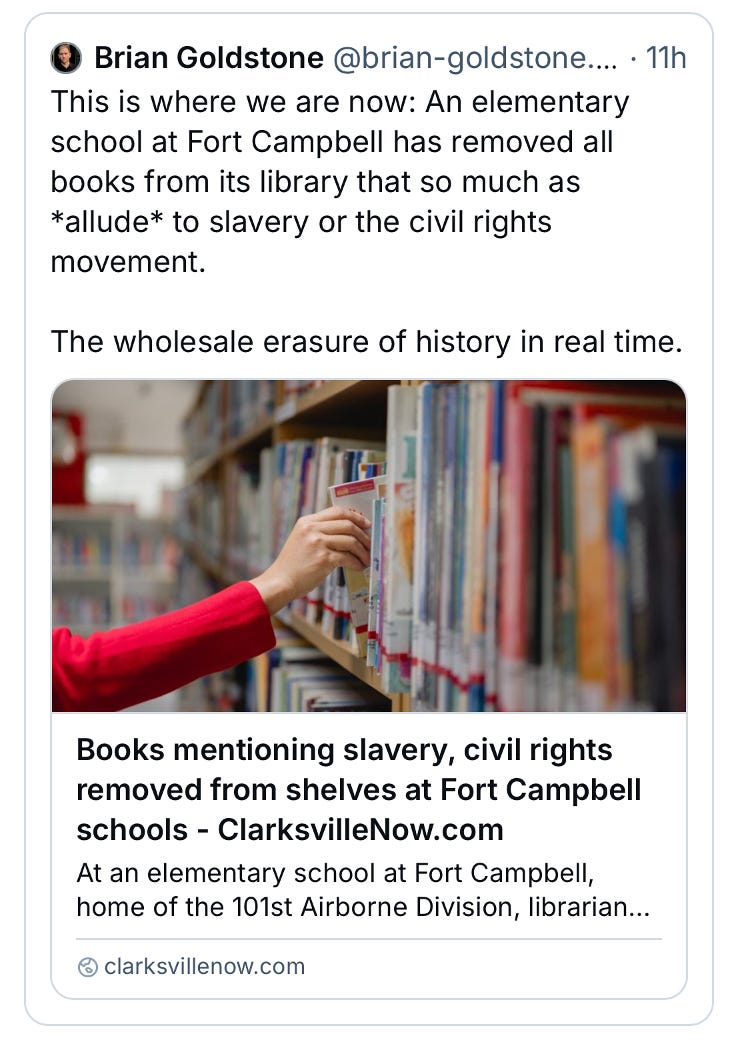

I’ll tell you what the lies don’t have in common: No lives are in the balance for the telling of them. While I don’t condone lying or deceit as a lifestyle, sometimes lies save lives, and you have to keep your hand in. Ask the enslaved; ask women being beaten by abusive husbands; ask Tina Turner running away from Ike. Ask Jews during the Holocaust. Ask the French Resistance. And as we are entering a different era now, hearkening back to those dark times, we all may need to reset our moral compasses. We are back to Nazi Germany, friends, and “truth” for them, ain’t truth for us.

Thinking about coded language and other “lies,” and this being Presidents Day, I recalled a Chaucer class I took in graduate school 30 years ago, and my professor, John Fleming of Princeton, wanted to teach the class about Medieval iconography—you know, the images in all those beautifully illuminated manuscripts with the stories in calligraphy and the illustrations in gold leaf and lapis blue. Those illustrations, we learned, were included not only for their beauty but to guide the illiterate, because unless you were nobility or clergy, you didn’t read. So, what did the images mean? You see a lion, a rose, stuff like that. How would anyone get a whole story from a picture?

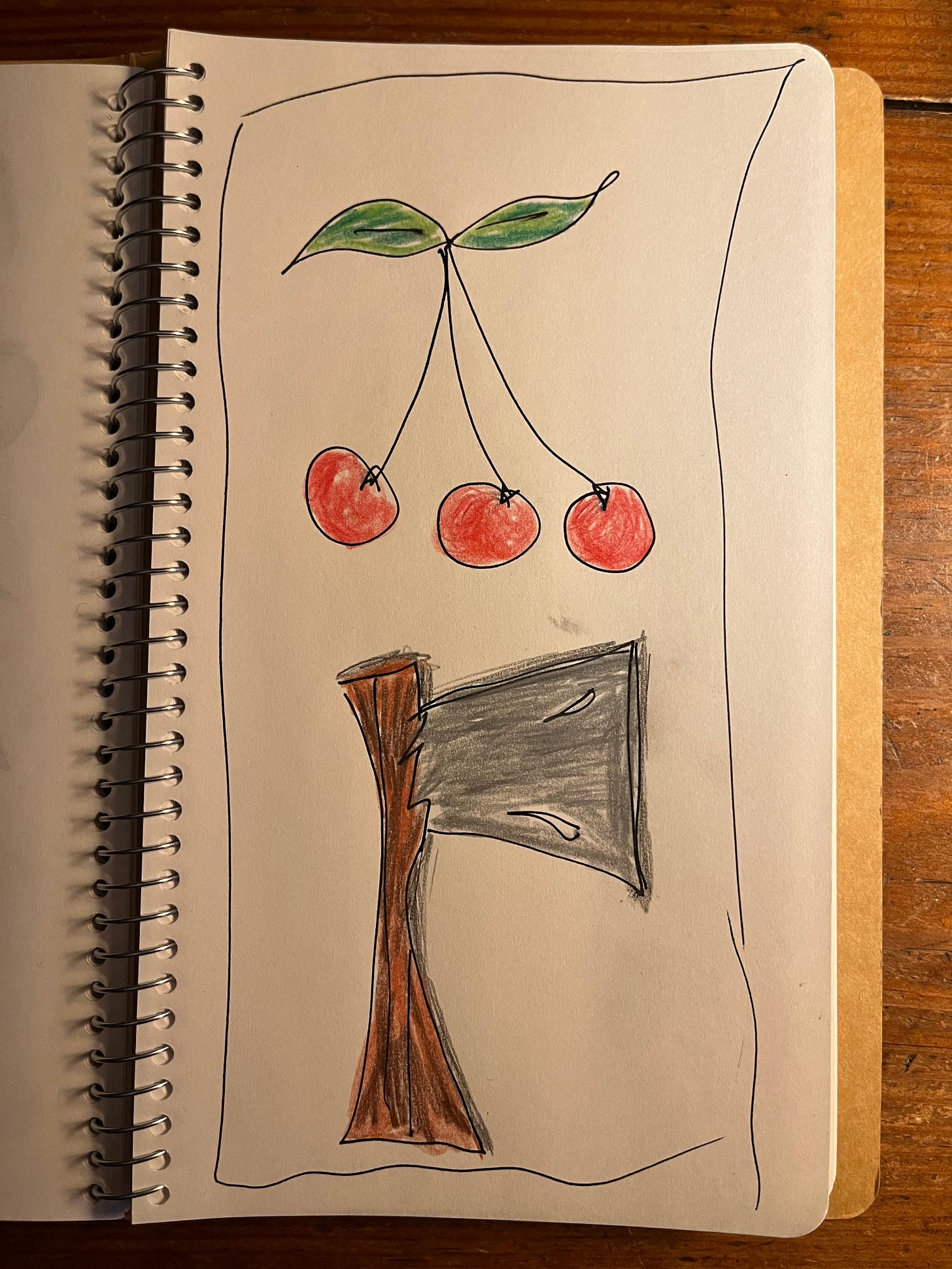

To demonstrate, Prof. Fleming drew these images in simple lines on the chalkboard:

“What is this story?” Fleming asked. My classmates, attending the Bread Loaf School of English from all over the country and the world, sat dumbfounded. I couldn’t believe it. See, I talked a lot, and I was practicing restraint, but finally I raised my hand.

“It’s George Washington and the cherry tree. I cannot tell a lie, Father, I chopped down that cherry tree.”

The class turned to me and looked at me like I had two heads. Fleming barked a happy laugh.

I explained to the still-lost class that I grew up in Virginia, up the highway from Parson Weems’s house, Weems being the man who wrote the fable about wee George, and a few miles down from Mount Vernon.

Fleming then went on to explain that this is a perfect example of how and why iconography—the use of simple symbolic images to represent a whole story—works in places that share a common culture.

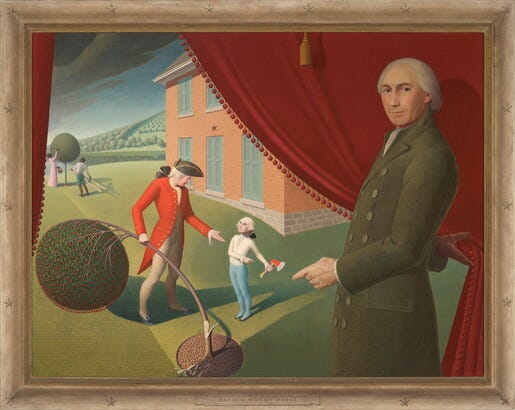

Who chopped down that cherry tree? asks George’s father, according to Parson Weems, who wrote, “Young George bravely said, ‘I cannot tell a lie… I did cut it with my hatchet.’ Washington’s father embraced him and declared that his son’s honesty was worth more than a thousand trees.”

Why create this myth about an already mythological figure, even by 1800? I guess to impress upon America’s youth the importance of honesty. But what to do when you learn the story is in fact made up?

Growing up as I say, along the Richmond Highway between the home of Parson Weems and Washington’s home of Mount Vernon, I learned this fable in elementary school, but I never learned about Washington, the enslaver. Not in high school, not in college. I remember a California friend visiting Mount Vernon with me and saying, “I thought this was just a myth,” meaning the whole plantation, the first American president, all of it. And it’s easy to see how anyone not from the historical grounds of colonial America might feel that way, or wouldn’t be shocked to see a slave auction block landmarked in Fredericksburg or Williamsburg, given the American tendency to mythologize the successes and sweep the ugly truths under our antique hooked rugs.

And really, the more we keep digging, and the more lenses we train on our history, the more truths we uncover, the more lies we reveal—the more interesting and complex and real our history becomes. It’s discomfiting, sure, horrifying at times, but isn’t it exciting, too? Isn’t truth worth seeking? How else to make this nation truly free?

This is where we turn to our artists.

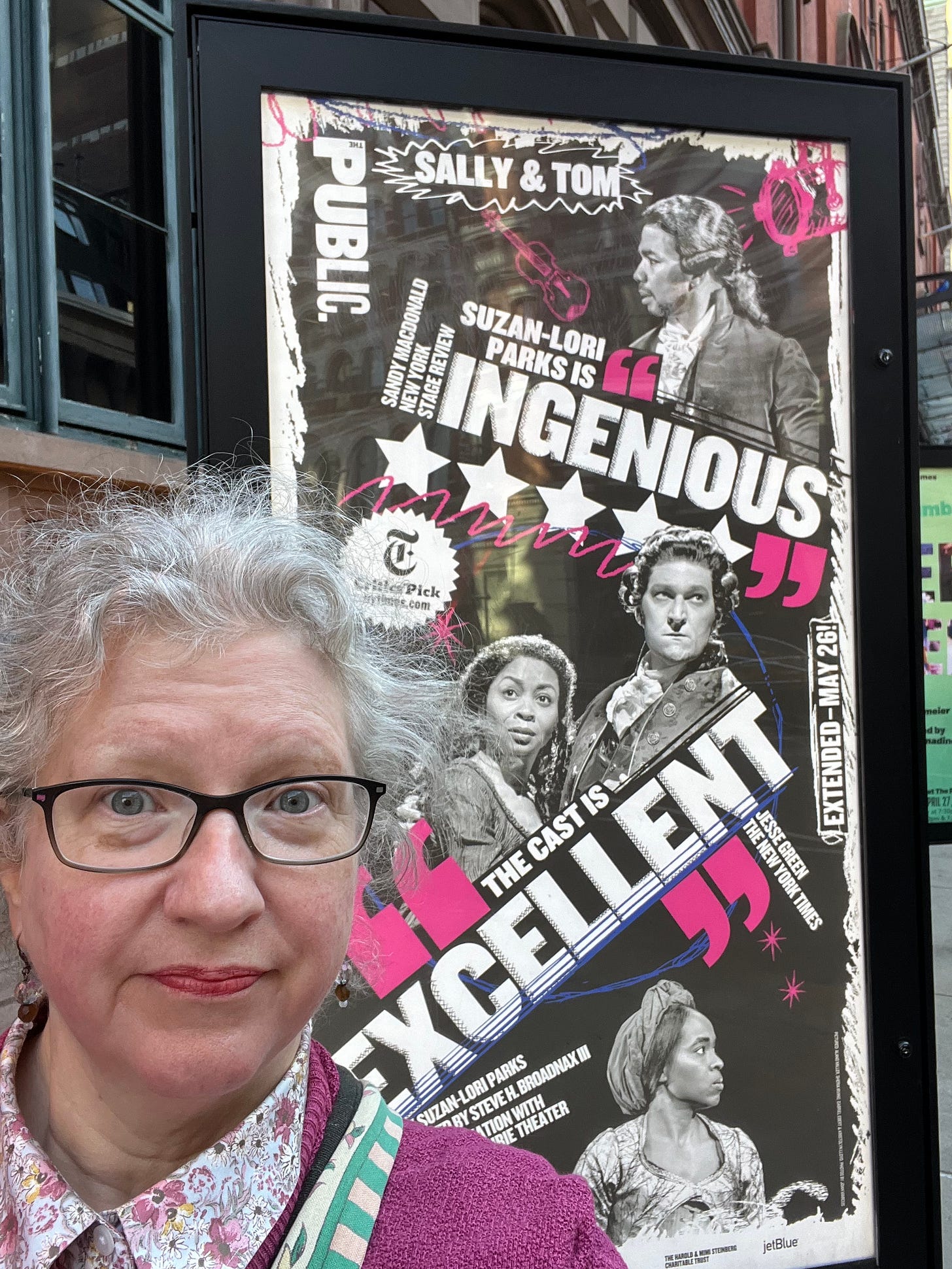

To explore perhaps America’s greatest “Lives of the Presidents” cover-ups, the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and his enslaved “mistress” Sally Hemings, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks premiered her play Sally and Tom at The Public Theater last year. The premise of the play is a community theater putting on a play about these historical figures while the leads are in a relationship. I loved the show, and I was fortunate enough to be there on a talk-back night. In attendance that night were several of the descendants of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings and their families, as verified by DNA. I couldn’t believe I was having this chance to witness history. To watch as these family members meet one another after the show (many were sitting in the row in front of me) and walk up onto the stage—the set’s back wall covered in all of their names in the final reveal—to take photos with their phones, made me weep. (I think it would be a fascinating way to end the actual play.) It was wondrous, too seeing truth all up there like that. The theater was filled with love in the midst of revelations. That’s what art does.

And I think also of that incredible painting by Titus Kaphar, “The Myth of Benevolence,” offering another way that art can reveal a deep truth in a way no historical record ever can, exposing long-hidden damage and forcing us to confront it. (Click on the link to see the entire painting and learn its story.)

A whole story from a picture. American iconography.

On what occasion do you lie? I look at the American story, then and now, and it’s seeded with lies and corruption, so many lies, you have to wonder, Can it ever come clean? How do we answer for it? These are the questions we all should ask and answer now. If we don’t, whom do we think we’re protecting?

On what occasion do you lie? Ask Gil Scott Heron, famous for saying “the revolution will not be televised,” meaning it happens inside us, speaks volumes about the impact of lies in the linked poem; and Kendrick Lamar, whose brilliantly coded and performed all-Black Superbowl Halftime Show blew me away. The enslaved lived in world of code. They had to lie about learning to read, for godsakes. Pretend to go along, to get along.

On what occasion do you lie? Ask women who have been sexually assaulted and been made to keep quiet or lose their careers. Ask the men who keep pretending nothing happened. Ask Sally Hemings.

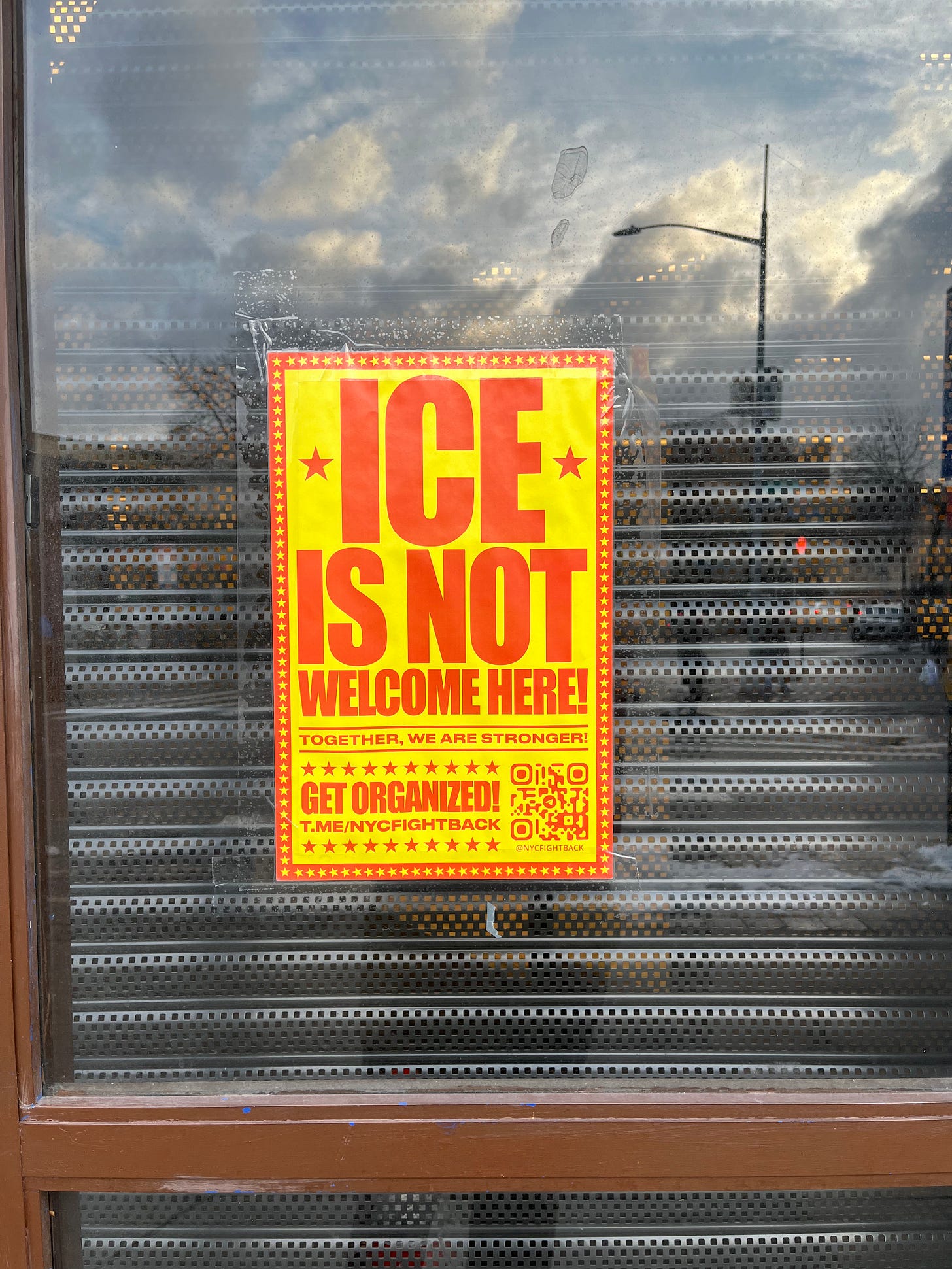

On what occasion do you lie? There are real reasons to lie, moral, ethical reasons. To protect the ones we love. To save our neighbors. We are having to think hard about that now.

Because let’s face it: here in the United States, we are in a crisis of government amorality. We have a lying Republican party (no more rule of law); a lying president (pick a campaign promise, and yes, Project 2025 was the plan all along); a lying vice president (his autobiography exposed as a sham); a lying Supreme Court (see Roe v. Wade, which all declared, under oath, “settled law”); and liars heading every cabinet position (no, trans people are not the cause of America’s problems; and Putin is not America’s friend, Tulsi). We have liars in the Department of Justice and Homeland Security (immigrants are not remotely the cause of most crime; being brown is not a crime). We have liars heading the F.B.I. (the Democrats are not the enemies of America). It’s all lying all the time, now, and their truths are even worse. The freedom of Western Europe is now in the balance, as Vice President J.D. Vance admonished the “values” of those democratic nations this weekend, in essence praising the rise of fascism in France and Germany and also capitulating to Russia’s desire for empire. On the campaign trail, Vance said “democracy” but meant, we know now, “totalitarianism” (Europe is not America’s enemy, nor are Panama, Canada, or Greenland; our actual enemies are transparently heading our own government.)

To think that all of today’s stuff started with asking a simple question.

Identifying lies is not the same as responding to the world that supports those lies. There’s a very cool blog on Substack called The Pamphleteer by Lady Libertie, and she is focused on how we negotiate this new era. Check out “So You’ve Been Invaded: a French Resistance Guide for the U.S.” Pretending comes with the territory of survival. Marcel Marceau, for example, as a teenager pretended to be a camp leader, while his real job was to smuggle Jewish children across the border to freedom; he used the art of mime to teach the children silence as they walked. It’s not really lying if it’s saving lives, and the people you are lying to are venal.

Happy Presidents Day in America, 2025, everybody!

Sending love,

Miss O’