Ruminating on feelings of in between

Transition in Transit

Yesterday, I took Amtrak from Virginia to New York City, after two full months living in my parents’ house. (Bernie and Lynne are coming along, for however long they can.) Even though theirs is the house I grew up in, nearly all the aspects of it that made it home are gone or changed so significantly that it really feels like a different house. The 1960s offered a white house with green shutters, exposed asbestos tile floors on the half-basement level of the split foyer. During my growing up, when harvest gold industrial carpet took over the floors and steps and upstairs living room, so did the 1970s palette expand to bring in orange and avocado green and brown. In truth, my mom did this palette really tastefully and artfully, refinishing now tossed furniture pieces that I really miss, replaced in the late 1980s country makeover—suddenly a windfall of cash with no kids in college and two incomes allowed my mom to indulge her passion for blue and natural wood. The result is that I’ve known the present incarnation of their house only as a self-supported adult, so whatever there was of my home (my bedroom stuff pared down to a single large box back when I went to college), it’s no longer a built environment (objects of deep memory and family history notwithstanding) that I feel particular warmth for.

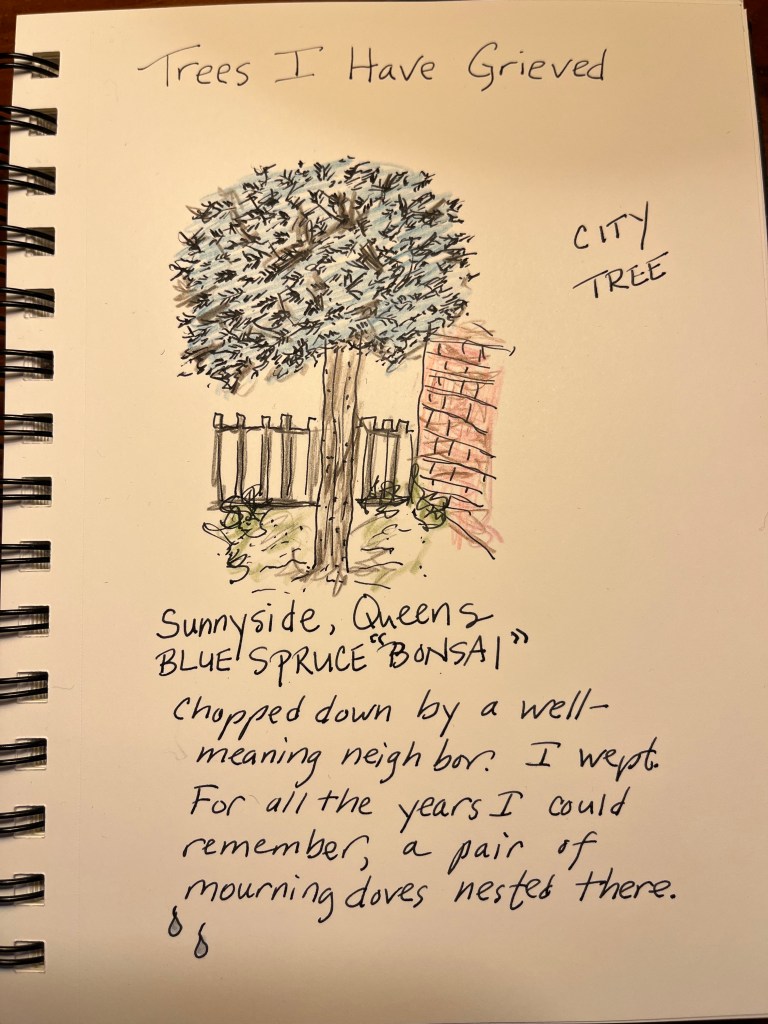

The curious thing is that my connection to the yard runs as deep as ever. The majority of my accessible childhood memories are tied up in grass, dirt, shrubs, trees; often, too, a swing set, a shed, a playhouse, a fort, though gone, appear as ghosts. I am always barefoot. The maple in the front yard has been my constant greeter for 59 years; the crepe myrtle, too. The oaks of various species in the backyard were there for decades before I was born, and the hickories have grown up with me. The holly trees, shrouded by the taller deciduous trees, have never gotten really large, but they are my age, at least. (I can still feel the prickly fallen leaves lodge in my heels.) It is to the yard that I want to go when I get home, to feel that I’m home.

You Can Be Anyone You Want to Here

My Aunt Mary from Iowa said the above when she was standing on Canal Street, her first visit to New York, in 2004. I would add, “If you can make it here.” My home for the past 20 years has been a co-op apartment in a 90-year-old building in New York City’s borough of Queens. Coming off the train into Penn Station yesterday, wearing an air cast on my left leg (over my black travel slacks, to prevent a rash from the plastic—menopause has a been a blast, you guys) and a gray combat boot over my slacks on my right leg (for not one but two sprained ankles!), carrying a large sling bag, full backpack, and computer tote bag, not a single person gave a flying fuck. And that is the price you pay for all that freedom to be you doing you: supreme indifference to my personal human plight. I’m always agonizingly aware of my own complicity in this survival game as I pass homeless people without giving alms, in my rush, I think, which is really avoidance of culpability. For that reason, I don’t begrudge anyone racing past me up or down the dozen flights of stairs I had to take to find a working subway going in my direction (midtown was pure gridlock so any cab or Uber was pointless, unless I wanted to spend three hours getting back to Queens). All I know is that as I trudged past construction on 7th Avenue and 33rd Street that has literally been in progress for SEVEN FUCKING YEARS, with no end in sight; past orange cones and trash and and scaffolding and pilings and strollers and tourists walking past all the chain store banality that is 7th Avenue four abreast, down steps (foot-foot, foot-foot) where I have to inch past guys blissed out on weed; into the bowels of Times Square only to find out the 7 Train is not running; up the four flights of stairs (foot-foot, foot-foot) to the N Train (because the escalator up starts down by the 7 Train, and those stairs are blocked off and are being policed); and by now in the global warming October heat with the schlepping and the sore ankles and endless walking, shoved or ignored, and feeling by this point a little weepy, I really had to ask myself, seriously, “Why the fuck do I live here?”

And later, in my own bed, unable to sleep from ankle pain and the chill and recalling the stack of mail and all the unpacking and plugging in of laptops and texting people I’m back—I realized I really do hate living here. I have, as of November 1, been living in this apartment for 20 years. Of those two decades, only the first one was good. In 2013, my play lab ended, my work role changed to working essentially for a partner start-up, I had a miserable month of grand jury duty, and I met a man who gave me the deepest love and caused me more grief over the next decade than I want to speak about. And, post Covid, I have accomplished exactly zero as a creative person. As I now work exclusively “from home” (great for flexibility if not sociability), I see almost no one—a dinner here and there once or twice a month. My old building needs too much work. Global warming is creating a flood plain out of the city. And I’m going to be 60.

I turned on the light then, because I had this flash of memory, of going with my college friend Richard as his plus-one to his cousin’s wedding in New Hope, Pennsylvania, back in 1985 or so. The downtown was lit up at night, even in summer, with white fairy lights strung here and there. Everything about the place was joyful and cozy, people out and about, shop windows so inviting. This was like Blacksburg, home of our college, Virginia Tech, without the carousing drunk frat boys. Ever since, I have dreamed of living in a town that felt like that—creative and joyful and pleasant, but with diversity, room for the middle class, and lots of live music and dancing in parks and plazas in the summers. A community theater, concerts, art for people who lived where they worked.

I realize now that those places don’t exist ready made for me to walk into—an enchanted village in a story book that become real, like Brigadoon. Community like that, place like that, has to be built, and not presented as a gift. I have always worked very hard to create a life for myself everywhere I’ve lived. What is different now? I guess, looking at 60 and returning from nursing my parents as best I could, faced with two square feet of junk mail to sort (with unending gratitude to my upstairs neighbor, Debbie, who built that pile of junk mail, watered the plants, and ran the taps AND cleaned up my basement after it (mildly, mercifully) flooded with the remnants of Ian—see Brooklyn for reference)—I guess I’m really wondering about where I belong, what I do next, and how I do it. I feel, weirdly, totally lost.

On my way down the sidewalk near my apartment (all my gear by now giving me its full weight) past the playground, my eye caught a shiny object in the leaves along the chain-link—a New York driver’s license. I picked it up, someone on 41st Street. I’ll try to find him tomorrow, I thought. (This morning I strapped on my “casts” and went out in the rain over to his apartment building, buzzed his number, no answer, so I left it on the ledge above the buzzers—and then I spent the next two hours beating myself up for not thinking of MAILING it back to him.) It’s a small but common event for me in this vast city, helping a stranger in an odd way. Sometimes I wonder, given the last decade of my life, if all I’m really here for is not to be an “artist,” but really to be a clean-up crew of one, one human accident at a time. Maybe that’s who I am, and these notions that I should accomplish more are foolish expressions of ego.

After all, unlike too many people, I have not one but two roofs to shelter under, at least for now. Trees to visit. Good neighbors. Friends, however much they are only available via text. It’s a crazy modern world, and there’s no good where to be unless we make it the way we like it. Where my next home will be or how I remake the one I’m in, I can’t know, but in my heart I know the search is on.

Hope you are feeling home in your own heart. I saw this quote on a meme recently, and it hit…home:

Home is not where you were born; home is where all your attempts to escape cease.

~ Naguib Mahfouz

Love to all.

Miss O’