Featured on my kitchen wall is a framed series of five photos, one under the other, that depict me and two other women rolling down a green grassy hill. My friend, Patty, a professional framer, matted and framed this series for me many years ago, though why I wanted it, no one understood. I knew why, so really that’s all that mattered. And though it’s framed nicely, each time I look at it, I get stuck at the last two pictures. To me they are in the wrong order. The second to last one in the frame shows me and Roller No. 2 sitting up, my fists raised in triumph, my legs up, ready to do it again. The last one in the frame shows the Rollers 1, 2, and 3, passed out blissfully on the grass. The trouble is, the action happened in reverse of the order: We were passed out blissfully, and then we popped up and went back for one more roll. However, as Patty pointed out, anyone looking at the series would be aesthetically unsatisfied with that—she insisted that the three of us collapsed at the bottom of the hill was the right feeling of “this is the end.” I didn’t agree, but she was a terrific artist and very sure, and I just wanted to hold the memory, so I let her tell the story her way. It’s a story that, if you weren’t there, maybe made more sense.

Here is the real story: They were middle aged, these three women, and I had just turned 30, and we were teachers in graduate school for the summer. Three of us were housed in a large mansion-style dorm atop a big hill, and I had remarked on the day of our arrival, “This is a perfect hill for rolling.” I was wistful. The two women on my floor whom I mentioned up there, Anna (the photographer) and Suzanne (Roller No. 3), had no idea what I was talking about. Anna had grown up in California where there were no green rolling hills, and the same was true for Suzanne, whose landscape was Midwestern, up northern way. That very same evening—our first of the summer—Annie from Mississippi came up to the house on the hill, and from upstairs I heard her say, “This is a perfect hill for rolling!”

I flew through the door to the upper porch, where my room was set, leaned over the balustrade, and called, “Annie! Will you roll with me?”

Anna, from across the hall, called, “Wait for me!” and came out of her room with her camera.

Suzanne, next door, said, “You mean I get to SEE this?”

I said, “You have to DO it,” and we three raced down the stairs with that child-like rush of feeling—as if, if you don’t hurry, your chance will be gone forever—and outside, where Annie and I taught Suzanne her options: either arms crossed over your chest, or arms outstretched over your head. We spread out. And…GO! Somehow in that flash of chaos, Anna had managed to capture, 1) me rolling alone; 2) a shot of Annie and Suzanne rolling; 3) all three of us from a crotch view, slightly blurred; 4) us three flopped on the ground, three pairs of jeans and shirts of pink (me), lavender (Annie) and purple tie-dye (Suzanne) all against that deep, luscious green; and 5) me bent in a V from my butt, arms and legs up, and Annie, sitting with arms back, her face in a smile, and we’re ready to go.

That is the real story, the real sequence, but because it doesn’t read as the usual narrative, or the most tightly constructed or aesthetically pleasing narrative, I’m the only one who would look at the series and be dissatisfied. Or would I? In truth, I don’t think anyone has really ever looked at it outside of me, because it’s not exactly a universal story, or even a “lovely” portrait of any person, or of nature.

So what does it mean to tell a story “the real” way? And does it even matter?

When I was in college studying to be a teacher—which is as antithetical as it sounds, for as every professor of “education” will acknowledge, nothing they are teaching will be useful for at least three years into teaching, when experience would make it make sense; and my own view is that what they should be teaching is how to write a bathroom pass and not lose your train of thought in an instructional moment—I was fortunate, and I mean beyond lucky, to have two guest professors when I took Psychology of Education I and II in summer school. I’ll call them Ms. Lettuce and Ms. Lovage (with apologies to Terrance McNally). Both teachers were invaluable to me, but Mrs. Lettuce was the person who got me thinking about the “real” story.

As a first-year teacher in a coal-mining town in West Virginia—a town and culture she’d never before encountered—and on her first day teaching first grade, Miss Lettuce decided to start off by reading to her students “The Story of the Three Little Pigs.” When she got to the first instance where the wolf “huffed and he puffed and blew the house down”—the house of straw—a little boy in the front row said, “That son of a bitch.”

Mrs. Lettuce turned to the class, most of us either gasping or giggling, and asked, “What do you think I should have done?”

You know what’s great about her question? THIS moment is exactly the thing that university departments of education never teach you, the kind of thing that will happen to every new teacher in every new school on every single new first day of school in America, now and then and forever: the kind of moment that makes you quit by the end of the first year, after day after day of these moments, with no story to guide you.

Several of us teachers-in-potential raised our little hands, either pontificating on why he needed a stern punishment and a meeting with his parents, or gently suggesting that the teacher rephrase the remark to something more appropriate and speak to him in private later. Mrs. Lettuce said, “Why didn’t any of you ask how the other children reacted? Did you assume they laughed or gasped, too?” And it made me think: Why don’t we ever stop to ask something as basic as that, about context, to step back and look at the whole picture? She continued, “When that little boy said, ‘That son of a bitch,’ all the other children nodded,” and here she mimicked their very solemn nods. “Now what do I do?” No one in my class said anything. “Because you see what’s going on here, don’t you?” she asked. And we didn’t. “If he said that, and the children agreed and accepted it, that tells me that everyone in this community, in this culture, talks that way, that all their parents talk that way. I saw immediately that if I corrected him, I’d be correcting all these people I didn’t know. And I am the outsider, remember.”

So what did she do?

“I said, ‘Would you excuse me for a moment?’ and I went out into the hall, closed the door, and laughed. When I got myself together, I went back in, and I said, ‘I’m sorry I had to step out,’ and finished reading the story. That’s all.”

What Mrs. Lettuce realized was that the story of this culture was not her story, and so not her story to alter. It was her story to learn. And she passed that story onto us. (And this story helped me stay for three years in an alien rural school system where, in the view of many, I had no business to be.)

And as to the reaction that the child back there expressed about the wolf, “That son of a bitch,” was he wrong to feel that way? In fact, children have an innate sense of morality. Vivian Paley, a Chicago teacher and great researcher of children, relates in one of her books (I don’t remember which, and I think it was Paley, so I hope I’m not misremembering) a similar experience of reading “The Three Little Pigs” to four-year-olds.

First, let’s recall the original Grimm’s fairytale: three pig brothers have to build homes, and the first pig builds with straw, the second with sticks, and the third with bricks. The terrible wolf blows down the first two houses, and eats the pigs, but he cannot destroy the house of bricks. That last pig lives. The wolf goes away. The end. The lesson: You need to work hard and take the time to build a sturdy house to protect yourself, or you will DIE.

But that isn’t the story most people in America know, and here is what Paley discovered by telling the version of the story in which no pigs die. She read the children what I’d call the Disney-fied version, where the brothers sing, “Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf,” and when the wolf comes, the first brother runs to the house of sticks, and when the wolf comes again, the two brothers run to the house of bricks, and then the three brothers trick the wolf and boil him in a pot. Disney, who really wasn’t one to shy away from violence—I mean, who can forget the death of Bambi’s mother?—for some reason didn’t kill off the pigs. Without those deaths, what is the lesson? Go ahead and be a lazyass pig—your brother will save you. That is not a good lesson.

And Paley’s young students felt that. When Paley finished reading, the children looked dissatisfied. One child asked, a little fearfully, “Is that the real story?” Other children asked the same question. They’d heard another one, perhaps, but somehow this one just didn’t feel right. And Paley told them they were right, that there was another version. And they looked afraid, but they wanted to hear it; and she told them, and they cried when the first two pigs were eaten by the wolf, but they were satisfied with the story, because innately they knew that this was life, that this lesson mattered. They wanted to hear the real story.

I think that inside of these children, of all children, must be a hundred thousand years of genetic memory. No one taught those four-year-olds about narrative structure, or ethics, or what happens in “real life,” and yet instinctively they knew the real story, what the true story ought to be.

I think American adults in general have lost their way when it comes to our real story, our national story, and the reasons for this go back to the Puritans, as everything does, with a view of life as something to be dictated by religious patriarchy rather than lived and experienced deeply, connected to the natural world and our own intuitive, honest natures. And so, as there must be one narrative, one story, to publish in the history books (for humans are still in need of a story, whatever else happens), we pick and choose the pieces we want to include in our collective story, and by “we” I mean white men, the majority culture, in power. I don’t write this in acrimony. That is part of our real story.

But here is the shame: The American story is not just Founding Fathers with capital F’s, the colonists against the British; or the Wild West, with capital W’s, with wars of cowboys against Indians; or the Civil War—which in much of the white South is known still today as The War of Northern Aggression—or even only wars. These stories, too often, have been reduced, in the popular imagination (until most recently and blessedly, Hamilton), to vague tales about ragged coats and red coats, white hats and black hats, blue and grey: they’ve become bloodless, artificial. What gets lost in these acceptable history book narratives is the deep story of the People: the thrill of the exploration of the oceans and discovery of new worlds and also the savage destruction of native people and cultures and lands; the astonishing bravery and also the emotional brutality of the Puritans; the deep Christian convictions of early settlers and also the hypocrites who took advantage of those convictions for personal gain; the astonishing growth of agriculture to feed the world and also the enslavement of Africans to make that growth possible; the growth of industry and also the exploitation of immigrants and the earth to make that growth possible; westward expansion and also the utter destruction of the native way of life; and woven through all of this, the story of women taking part in and helping shape all of these stories, shoulder to shoulder with men, with nearly none of that story recorded. This story of America is one thing AND the other. The story is huge and vast and messy and complicated and fraught. It’s a continuing story.

If four-year-old American children aren’t afraid to hear “the real story,” why are the majority of grown American adults afraid to hear it? Why are certain hugely powerful media companies run by white men, for example, so afraid of “the real story,” the true story, of America that they feel they must create their own narratives, narratives in which there must be good guys and bad guys, and the only possible villains can be immigrants, Muslims, blacks, or women, and the only good is the continuation and protection of white male greed using repression and guns? All over the news, this is too often the only story, or the story that a few others try desperately to fight against. But it isn’t the real story, is it? We know that it’s not. What is the real story?

This sort of story manipulation doesn’t belong only to America, and it surely can’t be laid on Disney’s doorstep, or even at the threshold of the corporate headquarters of Fox News. This deliberate, inorganic story manipulation has only been possible in the last few thousand years out of many millennia, when because of agriculture and surplus, nomads began settling into villages, where, out of laziness, really, a few charismatic men began duping and robbing the workers and families of these villages, amassing wealth, and then hiring the men they’d robbed to make weapons and form armies, so they, the overlords, could take even more, scapegoating races of people and creating the massive military industrial complex—models of this dating back to the building of vast flotillas of all manner of ships, the breeding of horses for riding, and the forging of iron weaponry, all made for the sole purpose of carrying out large-scale warfare, among the men of Egypt and Greece and Rome; among Vikings and Saxons and the Angles and Normans; among tribes everywhere, really, when one goes deep into the stories.

That’s the real story of the People of Earth.

And the only way to change that story—because it simply isn’t sustainable, resources being what they are—is to shift the power dynamic, to decide, as a People, that the sociopathic-lazy man-warmonger narrative is not only wrong, it’s silly. We could be having so much real fun when we aren’t facing real, naturally occurring dangers. More to the point, we are, right now, for real, a People in Crisis, a climate crisis, brought on by global warming born of industrial ignorance and, of course, greed. You can trace most any problem to the grasping greed of a few bad men. Wouldn’t it be amazing if we turned our story—focused all our warrior energy—into working to salvage and heal and restore our Earth?

Here is the story:

Once there were three women, all teachers, two middle-aged and one just turned 30. The young woman, from the eastern plain, saw a deeply gray, dirty world that cried out to be cleaned, to be respected, to be enjoyed, and to be loved. She shared her vision with the woman from the western plain and the woman from the northern plain, who agreed, because they had been thinking the same thing. And from the southern plain came another woman teacher, middle-aged, who cried out, “This is a great world, and it needs cleaning!” And the youngest woman called out, “Will you clean it with me, Annie?” And so it was. Western Anna grabbed her camera, to tell the story of the Great Cleaning, and Northern Suzanne, who hadn’t cleaned before and wanted to learn, joined the women of the East and South, and together from all four directions the women grabbed their brooms and flew out into the world to clean it up and make it live, and to tell the story.

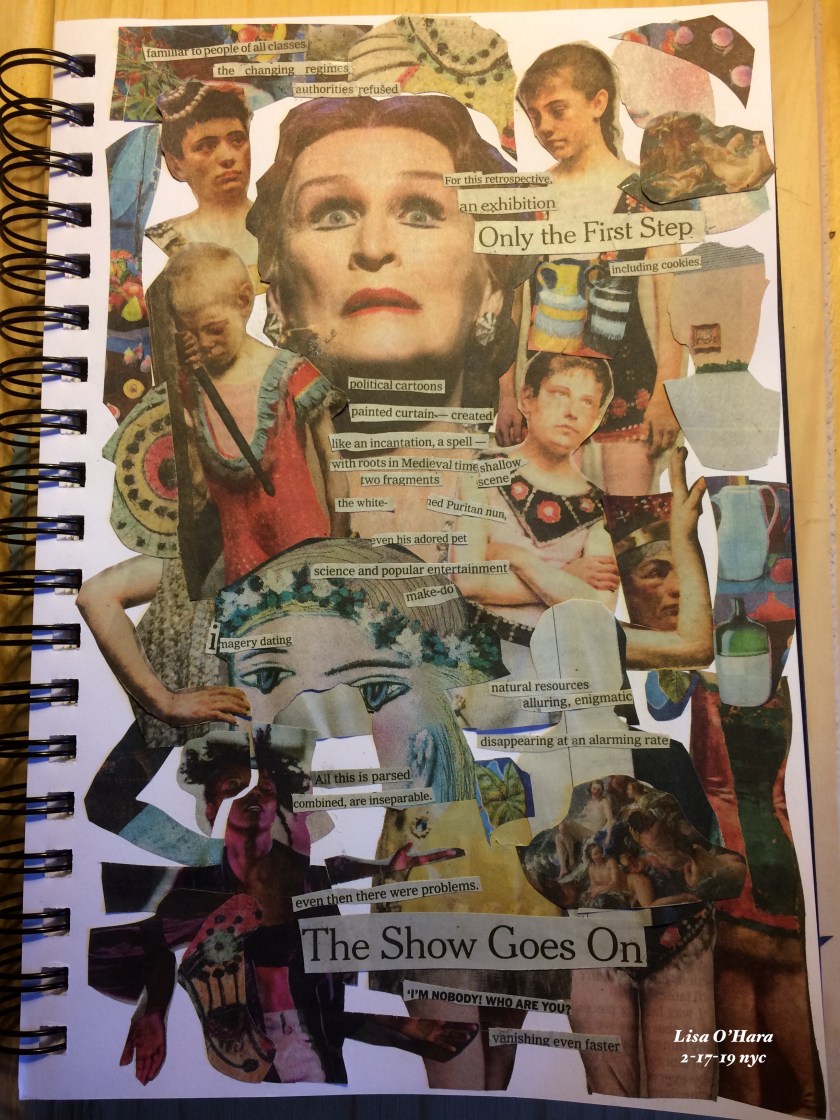

Here the storyteller shows the children the pictures that Anna had taken. The children notice that the person who framed the photos of the women in this story showed them flying out to clean the world, one by one, and the last photo is of them lying down, exhausted and finished with the work.

And here a child asks, a little fearfully, “Is that the real story?”

And here the storyteller pauses, and sees that she has to tell the truth.

“No. There is another version. Do you see that second to last picture? The one where they seem to be getting up to do it again? That comes last. You see, the work never ends. The story doesn’t end.”

And though the children were afraid at hearing this, and even cried, still they were satisfied. This was the real story.