A Daughter’s Care

Information Dispensary

Years ago, I was visiting an elderly friend in Virginia, a former landlady whose dear husband had died a couple of years before. Her wonderful, caring daughter, a school nurse by profession, had just left to return to her own house next door, having checked on her mother’s food, water, and meds situation, dispensing advice to us about this or that, and after she’d departed, my friend turned to me and said, “Merry knows just enough to be obnoxious.” It wasn’t that Merry was incorrect about her information, but it was rather the authority with which Merry dispensed the information that made her mother cringe.

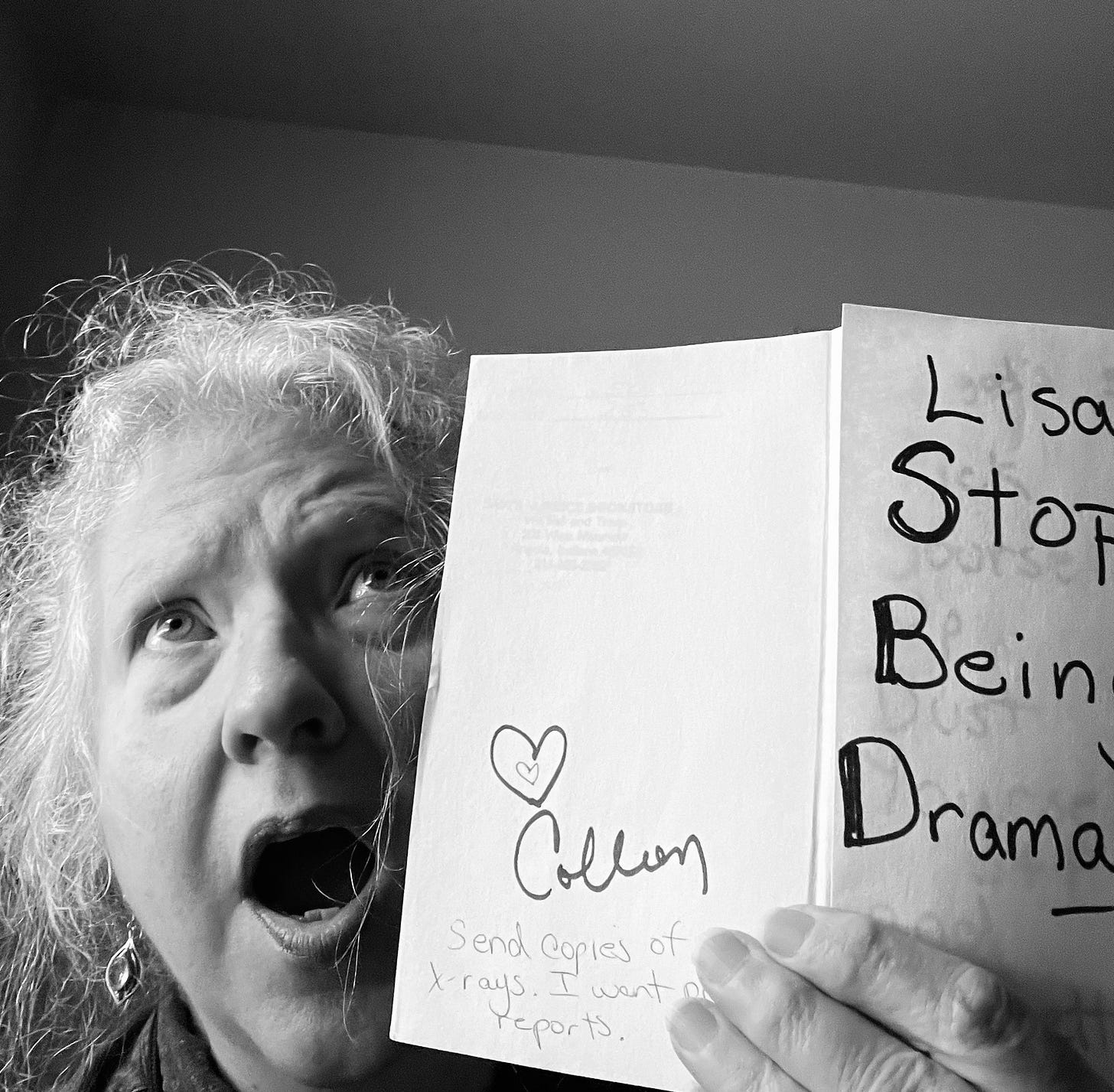

In the past weeks, I’ve seen that same reaction grow increasingly in my own mother, Lynne, who derisively calls me “Dr. O’Hara” when I hold up her water cup to take a sip. This morning she said, quite viciously, “Anything to shut you up.” That’s fine, I said. As best as I can gauge, my 80-pound mom drinks approximately one (measuring) cup of water a day, at most two. She sleeps nearly all the time, feels groggy and frustrated by her inability to wake up, so my pushing her to sip that dreaded water gives her the biggest rises of her day. The second great rise comes when I push her to drink (half, approx. 170 calories’ worth) of an Ensure. My mother is consuming approximately 500 calories a day, at best, as near as I can figure it. A bite of muffin here, a half a PBJ there, a bite of meat, a spoonful of potatoes, sometimes a few slices of pear, some Wheat Thins. My mom’s lack of appetite is a result of dehydration, and she’s dehydrated because, as for too many of us, dehydration does not register as thirst by the time the sleepiness or nausea sets in. And so it goes. It really doesn’t take a medical degree to know this, but the last thing medical professionals do is talk about food and water in the healing process, which is why idiot daughters like Lisa have to step in. It’s obnoxious.

Over the past couple of weeks, my mom—once her hip fracture more or less healed, the physical therapy began working, and her relative independence grew (she can now walk through the laundry room to the bathroom on her walker and use the toilet, all unassisted)—seems to have more or less decided (as of this writing) to accept stasis, which means, I guess, “give up.” She will be 90 in January, should she live that long (and I’m more than willing to be astonished by a sudden rally; just yesterday she asked her husband to trim her hair “with the scissors on the righthand side of your dresser, not the rusty ones on the left,” so who knows?).

I was talking to my half-sister Sherry yesterday, whose own mother is dying by inches, of Alzheimer’s, in a care facility (a housing decision she and our brother Craig had to make after their mom fell and broke her hip earlier this year), about my situation. Sherry worked in a retirement community for 20 years before herself retiring last year, so between caring for the residents and for her mother, she has seen a lot. In addition, Sherry worships my mom, so anything Sherry offers as advice, I know comes from experience and great love. Essentially, “if Lynne just wants to go to sleep,” Sherry advised in her soothing and practical-sounding North Carolina accent, “you have to let her. This is never getting any better.” On top of that, just before our talk yesterday, our dad had admitted to me that he had felt “messed up” in his head (how long? I asked; about a week, he said), which explained a lot about his more-erratic-than-usual behavior; and our brother Jeff was trying get him to go to the hospital though the old man was resisting. I told Sherry that I was concerned it was another ministroke, and I began choking up a bit, “We don’t know what to do, because he won’t do anything,” and Sherry said, practically and kindly, “Let him stroke out and end it. It’s all you can do when you’ve tried everything else.” (Coda: Jeff suggested, “Dad, do you think it’s vertigo?” My mom had said the same thing. As I was talking to Sherry, our dad knocked on my door and said, “I think it’s vertigo,” a chronic condition he’s had for about 15 years (one that caused my parents to have to stop traveling, after the third canceled trip due to the condition) but had not experienced for at least a year. We forget these things. So Dad took motion sickness medication, and within a half hour felt like himself. Crisis averted. And with that, Sherry and I began to talk about ourselves, our own trials, life in general, and find humor in getting on with it. I still can’t seem to get that humor into my writing, but my dear friends send me funny things.)

Death by Inches

On the Wednesday before my dad’s 90th birthday, during my fifth week here, my mom moving around a little better, the med situation stabilized (a fool’s belief, as it turned out, but life is moment to moment, you know), I made plans to go out for the first time, to lunch at 12:30 with my friend and former English department chair, Tom, meeting in a halfway-point town. Typically for schoolteachers, former and otherwise, Tom was an hour and a half early. He texted me at 11:00 AM that he had parked, it was “only four-hour parking” (teachers follow rules), and could I please “get here as soon as you can.” So I quickly changed clothes, grabbed my bag and my dad’s keys, said bye to the folks, and headed out to the family pick-up truck. Upon starting, I saw that the brake light was on, meaning the fluid was low. I went back inside, told my dad, who said it was fine. Incredulous, I headed back out; he followed me, said to pull the truck up into the driveway from the street, and as I stepped off the curb to do that, I somehow pitched forward, landing wrong on my right ankle, and then my left, banging a knee in the process, lying on the street behind the truck. A young Hispanic couple in a passing pick-up truck quickly stopped, had seen me fall, and the man got out and came over and asked if they could help, so kind. My dad came out just then with the brake fluid, saw me there, and whatever I may have tried to deny, I knew I had to go to the ER. I phoned Tom to beg off our lunch date, got into the car (thank goodness Bernie can still drive) (knock wood), and had my aged dad drop me off in front, where I inched into the ER on foot. (“Would you like a wheelchair?” Yes.) Five hours later, X-rayed (two sprains and a fractured foot), an air cast on one leg, a “combat boot” on the other, I called my brother Jeff to bring me home.

Now here is comedy: barely able to walk—and walk I must—I am unable to do basic caregiving; but more than that, I can’t return to New York until I’m fully healed, and sprains take weeks. New York is totally, utterly a walking city. Uber is expensive, cabs are expensive, and traffic is a nightmare (and one doesn’t Uber for two blocks up and back to the grocery store). I travel with a heavy backpack (containing my personal laptop and charger as well as toiletries and a few clothes), along with a small satchel containing my work computer, books for my job, my rain jacket, umbrella, and one extra pair of shoes (sneakers for walks, dressier slip-ons in case—just last year I had a funeral to go to). Probably 50 lbs. total. I was supposed to return to NYC October 8.

And just when you think maybe you can go back to your life, even for a few days, unexpected injury aside, you can’t: I found my father was wandering upstairs the other day carrying my mother’s pill case (the one I set up for them), confused about a missing pill—yelling at me, angry because “I never had any problem before,” that is before I, his daughter, set up this system. (I know just enough to be obnoxious.) If you’ll recall from a previous post—because this story is fucking fascinating, isn’t it?—for nearly a week after Lynne returned home, Bernie hadn’t given either of them their morning or evening meds; when I asked him what he gave them, and when, he couldn’t remember; and having had three ministrokes, Bernie is supposed to take one low dose aspirin every day (in addition to his blood pressure and cancer meds). He’d forgotten all about it until I reminded him. In addition, he’s been having panic attacks about food—after a lifetime in food service, including being a short order cook in the Air Force, a produce manager, and a meatcutter; he cooked half our meals during our growing up, and his panic performance each day over what to make for dinner could be a cabaret act. No amount of my brother and I saying, “we don’t care, we are grown people, just take care of you and mom” will make him understand that he doesn’t have to pack Jeff’s lunch every morning or cook his breakfast (he doesn’t cook for me, for the record, because I’ve always been independent; Bernie used to boast to all his friends that I raised myself). He screamed at me earlier in the week, when I told him not to worry about what to have for dinner, “I have people to feed!” When I told him he just had himself and mom to feed, that Jeff and I will be fine, he got even angrier. I came upstairs to write this, and told poor, long-suffering Jeff that I don’t know what to do, because this isn’t about food but his confusion. (And, as it turned out, vertigo.)

Our parents are our providers. It’s all they know. So, what I’ve finally come to understand, is that if he’s not providing, my dad doesn’t know how to co-exist with his grown children in the same house. But that’s just a small part of his anxiety. The main thing, of course, is this: life as Bernie’s known it over 60 years of marriage is ending. The great love of his life and his reason for living is slowing dying, dying by inches. He himself is physically strong but his brain could explode at any moment. It’s all coming to a close, all of the years getting out of poverty, the struggles and laughs, working toward a middle-class existence, raising your kids, building a solid life. It’s ending. And all his obnoxious daughter can do, really, is bear witness.

And all that I, that daughter, want right now, and no kidding, is to be able to take a walk around the block in the autumn wind. That’s it.

TV Dystopia, by Meters

This week, all over the media, we see how Hamas attacked Israel, another pogrom to wipe out Jews. Israel retaliated, another pogrom to wipe out Palestinians. We live in a dystopian world. To use weaponry instead of intellect and heart to settle differences is to show oneself to be the basest form of life. Moment to moment, day to day, Hamas (a terrorist group not to be confused with actual Palestinians) and Israel inch toward an unstoppable end; I am nearly 60 years old, and these horrors make up some of my earliest childhood memories, watching the 6-Day War on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.

And you realize that all those casualties of war now and over decades and centuries, all these displaced victims, are simply people who are trying to work, get married, give birth, take care of their kids, and care for their dying parents, and somehow plan for the future. Moment to moment, day to day.

And the people who perpetrate all this violence (see also: Russia against Ukraine, the U.S. against Iraq, pick a war) have no real ideas about governance, fair distribution of resources, or the creation of a loving and useful society. Raw power only spends itself and burns out until the next arms race, and the world’s sadists glory in the destruction while the loving ones rebuild, over and over and over and over again. (I have no solutions; I know just enough to be obnoxious.)

Last weekend, Jeff printed out my parents’ monthly bank statements so our mom can review them between naps. On Tuesday, Bernie got his partials replaced at the dentist, creating the illusion of a full mouth of teeth that can chew. Two days ago, with cold weather coming, Bernie got out the vacuum cleaner with the hose attachment and vacuumed all around the furnace; he replaced the battery in the downstairs thermostat. The next morning, I found him cleaning his electric shaver. Later today, he will make a batch of Lipton Noodle Soup for his wife. And have some himself.

And so the days go by. My ankles throb with pain. The evacuation orders go out overseas. I don’t know how to explain why, given that terrorist bombs aren’t (currently) dropping on our solid little suburban American house, I am yet so fragile, so weepy; why this relative ease feels so hard. I feel I am ridiculous. My parents’ hard-working life has come down to little more than consumption of media and packaged food and medications; yelling at their obnoxious daughter even as they are grateful for her help; and waiting for the end of it all, they hope, together. I think that is what troubles me—that there seems to be nothing but waiting right now. That this is what too much of life is—filling in the time between activities needed for life to continue as we wait to die; my shock that Beckett so clearly knew what he was about when he wrote Waiting for Godot. An old theater joke, “My life is a Pinter pause,” comes to mind. And the last line of that Sartre play: Nous continuons.

Until next time, with love to my two readers,

Miss O’